In the aftermath of wildfires, a crucial micronutrient found in soil can transform into a toxic heavy metal, potentially contaminating groundwater. This alarming discovery is detailed in new research from the University of Oregon, which examines how chromium, a naturally occurring element, changes from a benign form in rocks and soil to a carcinogenic one under the extreme heat of wildfires.

The study, published on November 25 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, reveals that simulated wildfire experiments on chromium-rich soils showed fires reaching temperatures between 750 and 1,100 degrees Fahrenheit produced the highest levels of harmful contaminants. The research highlights the need for a deeper understanding of how fires influence environmental pollutants and suggests that broader soil contaminant testing could be valuable in assessing groundwater safety post-wildfire.

Understanding the Transformation

According to Chelsea Obeidy, the study’s lead author and a soil scientist now at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, the increasing number and severity of wildfires in the Pacific Northwest motivated the research. “We were motivated to figure out if there was any contaminant link there, if fires could be mobilizing contaminants of interest,” Obeidy explained. She conducted the study during her doctoral research in the lab of Professor Matthew Polizzotto, an earth scientist and environmental chemist at the University of Oregon.

Chromium exists predominantly as chromium 3 in the environment, an element essential for human metabolic functions. However, chromium 6, often a byproduct of industrial processes, is a Class A carcinogen linked to cancers of the lung, sinus, and nasal passages. The oxidation process, which can occur over time as rocks weather or are exposed to extreme heat, converts chromium 3 to chromium 6.

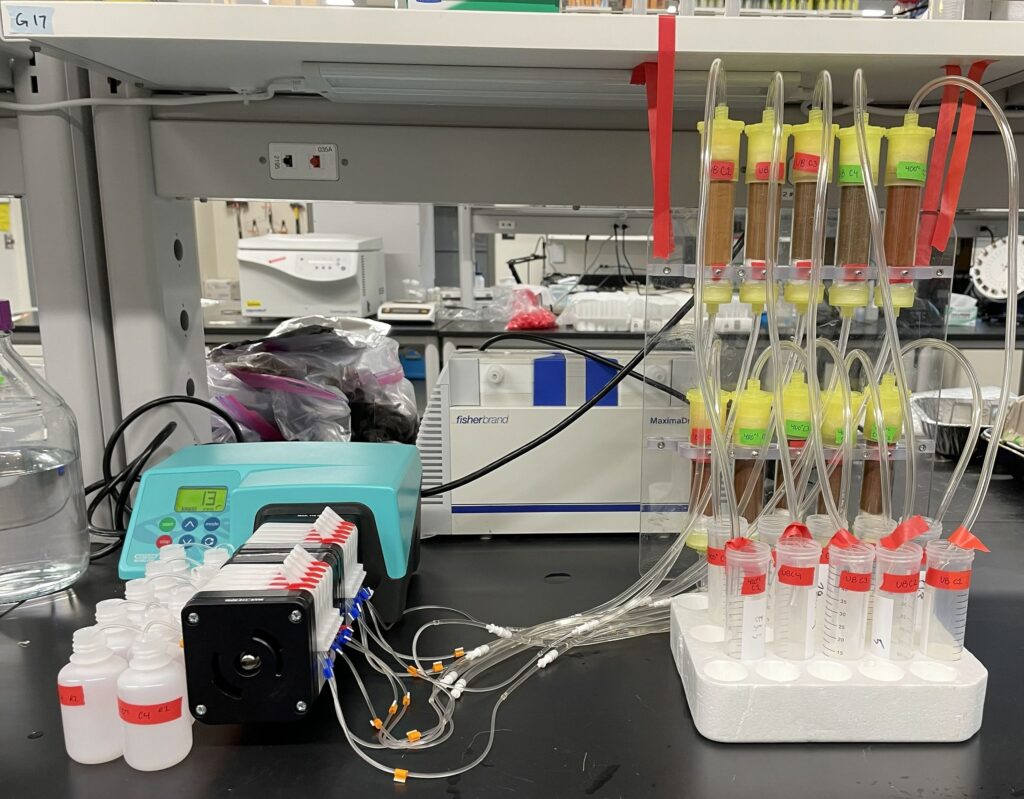

Simulated Wildfire Experiments

Obeidy and her team collected soil samples from Eight Dollar Mountain in the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, an area rich in chromium 3 deposits and increasingly at risk for wildfires. They sampled various elevations to capture a range of soil weathering, finding more weathering near the summit. The samples were then subjected to controlled burns in the lab, with temperatures ranging from 400 to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

To simulate rainwater leaching, the researchers packed plastic columns with the burned soil and passed rainwater through them for a week, representing about half a year’s worth of rainfall. They analyzed the drained water for chromium 6 to determine which soil locations could affect groundwater.

“Soils tend to be very variable,” Polizzotto noted. “They change over really small spatial scales. If we want to assess risks, we have to know the extent to which things might vary from place to place.”

Implications for Groundwater Safety

The study found that soils from and near the summit contained the most chromium 6 when burned around 750 degrees Fahrenheit. The summit’s increased weathering causes rocks to break down further, releasing more chromium 3 into the soil, which can then convert to chromium 6 under the right conditions. Conversely, chromium 6 emerged at higher temperatures, around 1,100 degrees Fahrenheit, closer to the bottom of the slope. Wildfires can vary in temperature, but they often reach these ranges.

Lower-intensity burns, such as prescribed or cultural burns, did not seem to produce significant amounts of chromium 6, though further investigation is needed, Obeidy noted. Depending on the slope position, chromium 6 could contaminate groundwater above EPA standards for six months to nearly 2.5 years.

“This could have a lasting impact on a burned landscape,” Obeidy said. “Maybe we need to be sampling after burned environments in these certain rock types.”

Future Directions and Environmental Considerations

Currently, the U.S. Forest Service assesses post-wildfire environments for erosion risk and human safety issues, but chromium 6 is not a contaminant they routinely test for. The study suggests that testing for a range of heavy metals, including manganese, lead, and nickel, could provide valuable insights into post-fire soil conditions, as these elements can also end up in soil and water sources after fires.

Polizzotto emphasized the nascent stage of this research. “We’re really at the infancy of establishing all the things we need to know,” he said, highlighting the importance of understanding the variability of contaminants in human-influenced landscapes.

The findings underscore the need for comprehensive environmental assessments following wildfires, particularly in areas with specific rock types that may exacerbate the conversion of safe minerals into toxic threats.