SOUTHEND, ENGLAND - MAY 26: A general view of portable toilets along the seafront promenade on May 26, 2024 in Southend-on-Sea, United Kingdom. (Photo by John Keeble/Getty Images)

In a world where synthetic fertilisers have revolutionized agriculture over the past century, a looming shortage now threatens to disrupt global food production. As the agricultural sector braces for impact, an unconventional solution is gaining traction among sustainability advocates: human urine.

Human urine, long recognized for its fertilizing potential, contains essential nutrients like phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium, mirroring the composition of synthetic fertilisers. However, the mining of phosphorus, a critical component, is becoming increasingly challenging. This scarcity poses a significant threat to food security, prompting researchers to explore urine as a viable alternative.

A Fertilised Future

Historically, civilizations such as those in ancient Rome and China harnessed the benefits of urine for plant growth. Today, the urgency to find sustainable fertiliser alternatives has reignited interest in this age-old practice. The phosphorus used in synthetic fertilisers is sourced exclusively from mining, a process with finite resources and environmental repercussions.

Without phosphorus, the production of conventional fertilisers will diminish, leading to potential food shortages. Experts suggest that using urine, when properly processed, could circumvent these challenges. Laboratories worldwide are actively researching methods to recycle human wastewater, extracting valuable nutrients for agricultural use.

What Can Wee Do?

Jordan Roods, a PhD candidate at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney, is at the forefront of this research. Funded by the Australian Research Council Hub for Nutrients in a Circular Economy (ARC NICE Hub), Roods explores innovative ways to convert urine into renewable fertilisers.

“The system isn’t geared towards looking at urine as a resource rather than as a waste product,” says Jordan Roods. “We’re not taking advantage of a lot of economic and social benefits.”

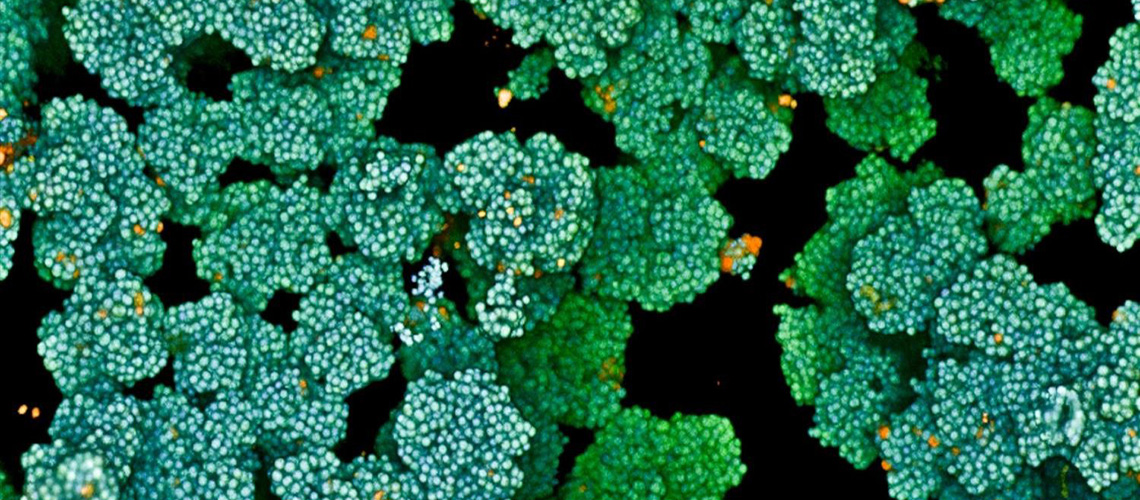

Most wastewater ends up in oceans, contributing to environmental issues like algal blooms. By rethinking urine as a resource, we can mitigate these problems while tapping into its economic potential.

Liquid Gold?

Urine-derived fertilisers offer a sustainable and cost-effective alternative to their synthetic counterparts. The Australian Government spends approximately $9 billion annually on wastewater processing, highlighting the potential economic benefits of recycling urine.

“By recycling it and using it as a fertiliser, you’re ticking multiple boxes: achieving food security, reducing water pollution, improving soil health, and creating new market opportunities,” explains Jordan Roods.

While direct application of urine on plants is feasible, processing ensures safety and stability. Techniques such as pasteurization, dehydration, and membrane filtration are employed to transform urine into effective fertilisers.

How-wiz it Done?

These processes enhance the nutrient concentration in urine, making it comparable, if not superior, to synthetic options. The NICE Hub is pioneering membrane filtration methods to concentrate essential minerals, offering a greener and cheaper alternative.

Separating urine at its source is crucial for maximizing its potential. While urinals serve this purpose, urine-diverting toilets in gender-neutral settings could facilitate widespread adoption.

What’s the Catch?

Critics raise concerns about antibiotic resistance linked to urine-derived fertilisers, though experts argue these fears are largely unfounded. The processing of urine involves pasteurization to eliminate pathogens and contaminants, ensuring safety for agricultural use.

“Separating urine at its source prevents contamination with faeces, which is where most pathogens would come from,” says Jordan Roods.

Overcoming societal taboos remains a significant hurdle. Public perception of urine as a waste product complicates its acceptance, but as awareness grows, so does the potential for change.

Low Cost, High Reward

The economic viability of urine-derived fertilisers hinges on their transportability. Decentralized processing, where individual locations convert their own waste, minimizes costs associated with transportation.

Unlike phosphorite, which is mined in limited locations, urine is produced universally, offering a readily available resource for fertiliser production.

Coming to a Loo Near You?

Globally, organizations are piloting urine recycling technologies. The US-based Rich Earth Institute, for instance, has developed scalable systems for onsite wastewater recycling, enabling communities to convert waste into fertilisers efficiently.

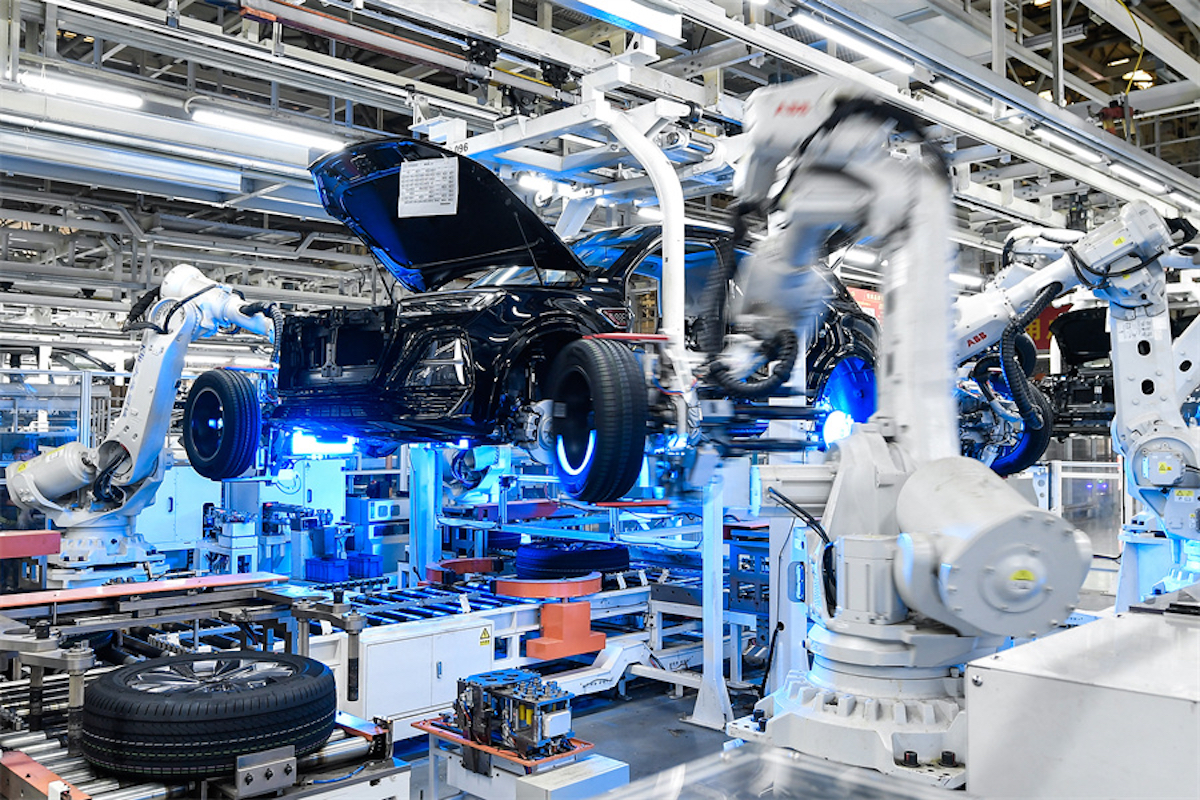

In Australia, Jordan Roods and his team have introduced a mobile membrane bioreactor system, dubbed the Loo Lab, to process urine at various sites, including the University of Technology Sydney and Sydney’s botanical gardens.

Despite regulatory challenges, particularly in Australia, where urine-diverting toilets were only recently legalized for research in Queensland, the momentum for urine-derived fertilisers continues to build.

“There’s a lot of friction still within the regulatory environment,” notes Jordan Roods. “Once lawmakers catch up, it seems inevitable that pee-derived fertilisers will play a key part in a green and (shockingly) clean future.”

As the world grapples with fertiliser shortages and environmental concerns, urine offers a promising path forward. With continued research and societal acceptance, this unconventional solution may soon become a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture.