The world’s most dangerous animal just became easier to study, and potentially, to defeat. Researchers from Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior, in collaboration with mosquito experts globally, have unveiled the first-ever cellular atlas of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. This species, notorious for transmitting more diseases than any other mosquito, is now mapped at a cellular level. The Mosquito Cell Atlas offers detailed gene expression data from every mosquito tissue, freely available to researchers and the public. The findings were recently published in the scientific journal, Cell.

“This is a comprehensive snapshot of what every cell in the mosquito is doing as far as expressing genes,” said Leslie Vosshall, head of the lab and a veteran researcher of the Aedes aegypti, also known as the yellow fever mosquito. “It’s a real achievement because we profiled so many different types of tissues in both males and females.”

New Insights into Mosquito Biology

The atlas has already provided groundbreaking insights into the genetic makeup of Aedes aegypti. Researchers discovered novel cell types and noted both subtle differences and unexpected similarities between male and female mosquitoes. Notably, the female mosquito’s brain undergoes significant genetic changes after a blood meal.

Nadav Shai, a senior scientist at both Vosshall’s lab and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, anticipates that the atlas will be a catalyst for future discoveries. “We believe this enormous data set will really move mosquito biology forward,” Shai stated. “It’s a great tool for vector biologists to take whatever interests them and just run with their own line of research.”

Organ by Organ: A Comprehensive Approach

In recent years, scientists have employed single-cell sequencing to map cell types and gene expression patterns in model organisms like the fruit fly, nematode, and mouse, resulting in comprehensive single-cell atlases for these species. Mosquito researchers have been piecing together similar data, but previous efforts were fragmented, focusing on individual organs or tissues.

Most prior studies concentrated on female mosquitoes, often neglecting males. “Both females and males feed on nectar in their day-to-day lives, but females need blood for protein to develop their eggs,” explained first author Olivia Goldman. Vosshall added, “Because the female spreads all the pathogens, there is a bias towards studying her biology, leaving a gap in our understanding of males.”

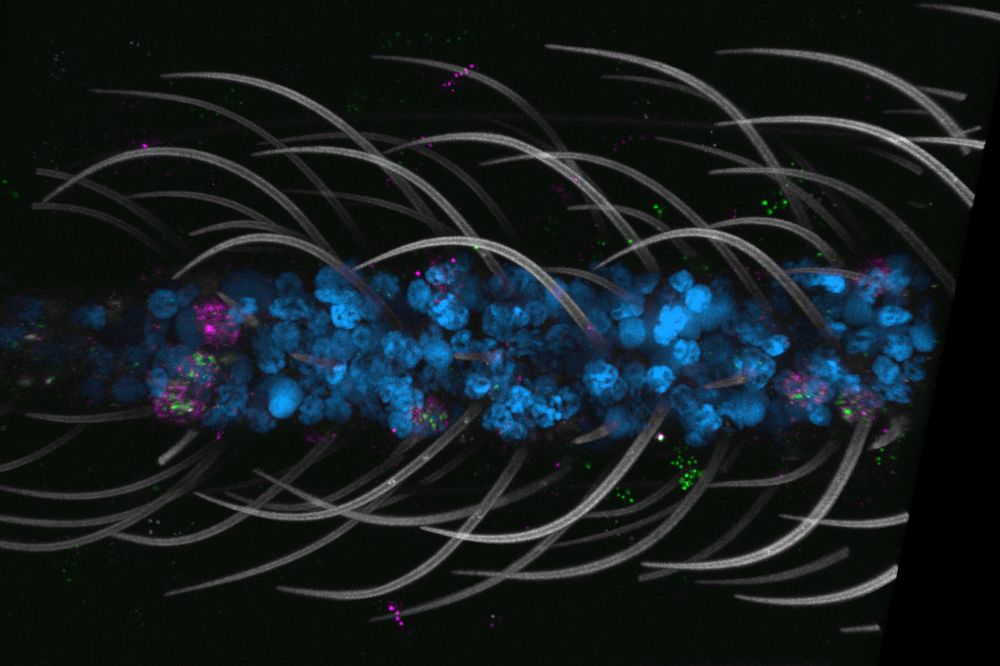

To address this, the team employed single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), which excels at capturing the biology of insect cell types. This approach generated a dataset of over 367,000 nuclei from 19 mosquito tissues, categorized into five biological themes: major body segments, sensation and host seeking, viral infection, reproduction, and the central nervous system.

Striking Discoveries: Sensory Neurons and Brain Changes

The research identified 69 cell types within 14 major categories, many previously unknown. Among the most striking findings was the prevalence of polymodal sensory neurons, which detect a wide range of environmental cues, including temperature and taste. These neurons were found throughout the mosquito’s body, including the legs, which can taste sweetness.

“Just like the antennae and maxillary palps, the legs and mouth parts have powerful tools for sensing the world,” Shai explained. “These sensors enable mosquitoes to excel at seeking hosts, feeding, and reproducing.”

After feeding, a female mosquito’s focus shifts from seeking hosts to egg development. “How does this incredibly strong drive to bite people get turned off?” Vosshall pondered. The team examined gene expression in female mosquito brains at intervals post-feeding, discovering dramatic changes, particularly in glial cells, which support neurons.

“The glia are completely rewired during this time when the females lose interest in people,” Vosshall noted. “It’s evidence that glia are crucial for both brain function and behavior.”

Implications and Future Directions

Another key finding was the limited sexual dimorphism in mosquito cellular makeup. Despite morphological and behavioral differences, male and female mosquitoes share largely identical cellular structures, with minor sex-specific variations.

The Vosshall lab plans to further explore mosquito behavior, such as host-seeking, using the single-cell atlas. “Different people in the lab are going to take it to different places,” Shai said, expressing hope that researchers worldwide will find inspiration in the dataset.

“This is a global resource that has been open to everyone since the project’s inception in 2021, so many people are already using it,” Vosshall added. “We’re excited to see the discoveries that will come from it.”