In 1974, Caroline Fraser was just 13 years old when Ted Bundy committed his first confirmed murders. Bundy, infamous for his charm and intelligence, was a sociopath described as “a sexual virus masquerading as a person.” Evidence suggests he began killing much earlier, but never with such intensity. Almost all his victims shared a common trait: long brown hair, parted in the middle. His methods varied from breaking into homes to luring women into his car under false pretenses. Fraser, living on Mercer Island, Washington, near Bundy’s initial hunting grounds, recalls the chilling moment he was first charged with murder in October 1976. “Everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who almost went out with Ted Bundy,” she writes.

Bundy was not alone. At least half a dozen serial killers were active in Washington in 1974. Randall Woodfield, the I-5 Killer, and Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer, soon followed. The state’s murder rate surged by more than 30% that year—nearly six times the national average. In Tacoma, where Bundy grew up and Charles Manson was once incarcerated, murder rates soared by 62%. It was as if a malevolent cloud had descended over the region.

The Toxic Environment Theory

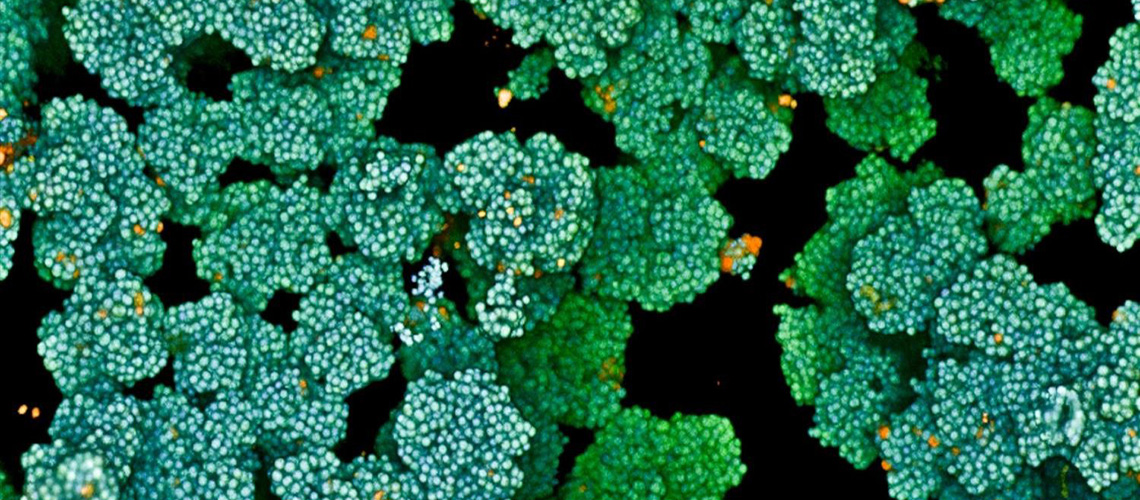

Fraser posits that this epidemic might be linked to an actual cloud—a toxic one. The Ruston smelting facility outside Tacoma emitted sulfur dioxide, arsenic, and lead. While the exact causes of serial killer behavior remain elusive, Fraser explores the lead-crime hypothesis. Lead exposure is known to reduce brain volume in the prefrontal cortex, which regulates behavior, particularly in men. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) now considers more than 3.5 micrograms of lead per deciliter in a child’s blood as concerning. Yet, in 1960, the “safe” threshold was 60 micrograms. As early as the 1920s, doctors noted that lead poisoning from paint made children “crazy-like.” By the 1970s, questions arose: “Does lead create criminals?”

“The unwitting populace breathes [lead], eats it, and becomes it,” Fraser writes.

The Guggenheim dynasty, through its company Asarco, was responsible for 90% of US lead production. Asarco acquired the Ruston smelter in 1905, converting it to refine copper, releasing waste metals into the air. In 1974, researchers found the smelter was emitting 25 pounds of lead dust and 58 pounds of arsenic into the air every hour. That same year, Asarco reported record profits, celebrating its 75th anniversary.

A Broader American Narrative

Murderland transcends typical true crime. Similar to Fraser’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, it’s an ambitious narrative about America and its people. Fraser’s work aligns with other literary nonfiction, such as Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, which pioneered the genre. Recent works like Patrick Radden Keefe’s Empire of Pain and David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon share thematic borders with Murderland. Fraser’s narrative is hauntingly compelling, weaving a rich tapestry of historical context and personal reflection.

Fraser’s prose is urgent and controlled, as she delves into archives to map a nation in turmoil. The year 1974, an annus horribilis, intertwines with the unraveling of President Nixon, the kidnapping of Patty Hearst, and Fraser’s own coming of age. By focusing on victims’ lives and avoiding grisly details, she sidesteps the voyeurism often found in serial killer histories.

Environmental and Social Parallels

Fraser’s narrative is interwoven with historical figures and environmental issues. Tacoma residents like Frank Herbert, who described the air as “so thick you can chew it,” and Dashiell Hammett, who fictionalized the city as “Poisonville,” are featured. The book explores the impact of figures like Thomas Midgley Jr., responsible for leaded gasoline, and Clair Patterson, who campaigned against it. The environmental catastrophe fueled by World War II’s demand for lead and copper is also examined.

The fear and vulnerability of the serial killer era—marked by unguarded hitchhikers and unlocked windows—are palpable. In the 1970s, nearly 300 men were actively seeking strangers to abuse and kill. This number plummeted in the 1990s, coinciding with the removal of lead from gasoline and the closure of major smelters. The Ruston smelter fell silent in 1985, primarily due to market forces rather than regulation.

“They’re doing the devil’s business, which is no different from what Ted does,” Fraser writes, highlighting the parallel between corporate ruthlessness and serial killers.

Concluding Thoughts

While lead pollution cannot solely explain the actions of serial killers, Fraser presents compelling correlations. Richard Ramirez, the Night Stalker, grew up near Asarco’s El Paso smelter. Gary Ridgway was exposed to lead paint for decades. James Oliver Huberty, who killed 22 people in a McDonald’s in 1984, was affected by cadmium fumes from welding. Fraser’s Murderland mirrors the incompetence of law enforcement with the failures of environmental regulation. The narrative illustrates a chilling numbers game, where some killers are caught and punished, while others profit.

In Murderland, Fraser crafts a gripping exploration of a dark chapter in American history, blending true crime with environmental and social commentary. Her work not only revisits the past but also prompts reflection on the present and future implications of environmental neglect and societal indifference.