Seals, among other mammals, have a unique reproductive strategy that allows them to delay pregnancy until environmental conditions are optimal. This phenomenon, known as embryonic diapause, enables a female seal to pause the implantation of an embryo in the uterine wall, waiting until her fat reserves align with the season. But how does an embryo, typically on a strict developmental schedule, manage to halt and then restart its growth seamlessly?

A recent study published in Genes & Development sheds light on this mystery by revealing how diapaused embryonic stem cells in mice maintain their pluripotency—the ability to become any cell type. The study found that these cells activate a molecular program that turns off pathways driving cell differentiation, a mechanism that might also explain how certain immune and cancer cells survive prolonged metabolic stress.

The Mechanism Behind Embryonic Diapause

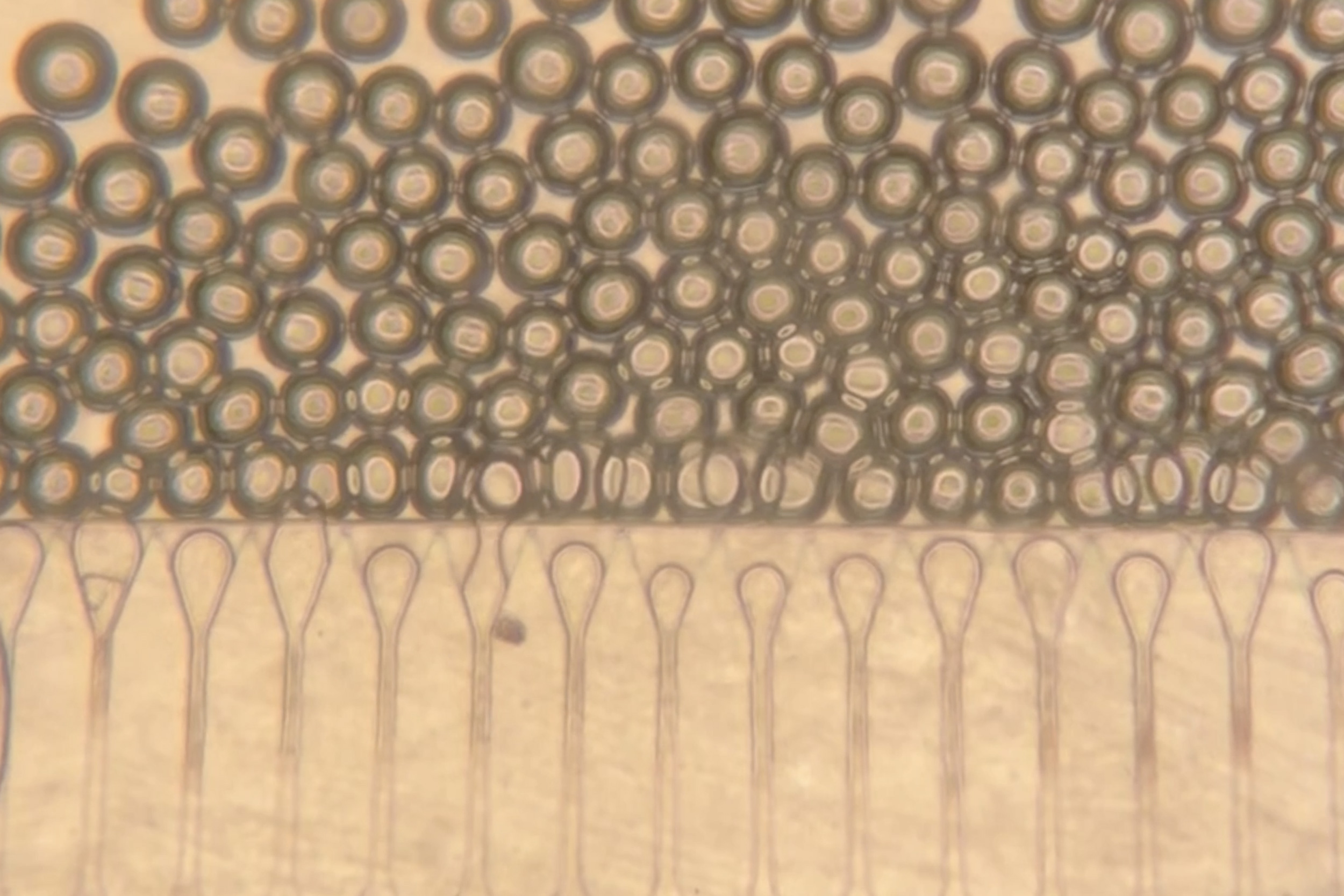

Embryonic diapause is a widespread strategy across the animal kingdom, utilized by mammals, fish, and insects alike. In mammals, this developmental pause typically occurs at the blastocyst stage, shortly after fertilization. The embryo remains in a state of suspended animation until conditions improve, at which point it implants in the uterine wall and resumes normal growth.

Previous research has demonstrated that embryonic stem cells can enter a diapause-like state in laboratory settings when subjected to various stressors. Blocking mTOR, a key regulator of cellular growth and metabolism, can induce diapause by shutting down pathways necessary for protein synthesis. Similarly, reducing Myc family transcription factors, which drive cell growth, can quiet gene-expression programs, pushing cells into a low-energy state. These findings suggest that diapause might be a protective default state triggered by diverse stressors.

“Diapause appears to be a state that can be reached in many different ways and due to many different kinds of harsh circumstances,” says Alexander Tarakhovsky, head of the Laboratory of Immune Cell Epigenetics and Signaling.

Preserving Cell Identity During Dormancy

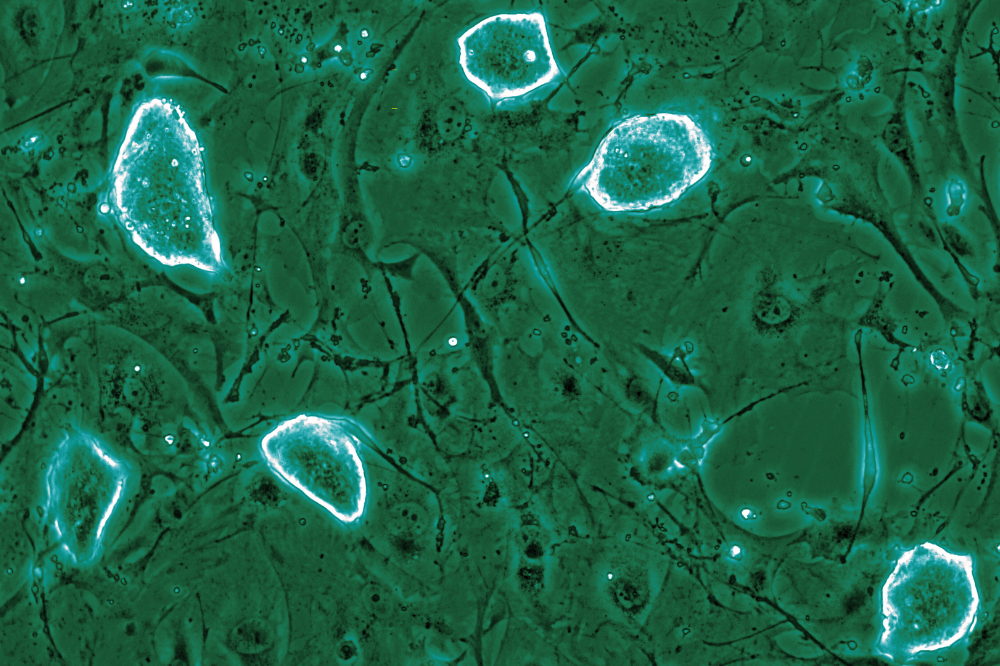

To understand how cells preserve their identity during suspended animation, Tarakhovsky’s team focused on the transcriptional program that maintains stem cell pluripotency under stress. They successfully induced a diapause-like state in murine embryonic stem cells using I-BET151, a BET inhibitor that mimics Myc deficiency, and mTOR inhibition to simulate metabolic slowdown. In both scenarios, the cells retained pluripotency while reducing metabolism, RNA production, and protein synthesis.

Upon closer examination, the researchers discovered that different stressors—mTOR inhibition, BET inhibition, and Myc loss—triggered the same core response. The cells activated genes acting as natural brakes on the MAP kinase pathway, which typically pushes stem cells to differentiate. When these brakes were turned off, the cells lost their pluripotency, confirming the braking system’s role in maintaining the diapause-like state.

The study further revealed that stressors displaced a protein called Capicua, which usually keeps these brake genes silent. Removing Capicua allowed the brake genes to activate, providing a molecular switch that maintains cells in a paused yet poised state.

Implications for Human Health

The findings highlight a molecular mechanism that allows stem cells to maintain their identity during dormancy, suggesting that diverse stresses push cells to activate a shared brake. This supports the view of diapause as a state emerging from network structure rather than a single regulator.

Tarakhovsky’s lab, known for its work in epigenetic control and histone mimicry, developed the BET inhibitor I-BET151 to induce diapause by mimicking the effects of Myc deficiency. The results underscore how regulatory networks help cells preserve their identity even when metabolism and gene expression slow significantly.

The implications extend beyond embryos. Many cell types survive by reducing metabolism for extended periods, and this molecular brake may explain how immune cells persist for decades, how stem cells retain their identity in stressful environments, and how some viruses and cancer cells can remain dormant before reactivating.

“Humans don’t experience diapause—we aren’t hibernating like bears, and our embryos don’t enter suspended animation under stress—but there are cells in our bodies that do,” Tarakhovsky says. “With studies like these, we’re hoping to gain insight into the general principles that explain the cell dormancies that impact human health.”

The research team is also investigating whether diapause-like programs influence neuronal aging or resistance to damage. Ultimately, this study positions diapause as a valuable model for understanding how organisms and cells endure metabolic stress, providing a framework for exploring dormancy across biology.