Some tropical land regions may warm more dramatically than previously predicted, as climate change progresses, according to a new study from the University of Colorado Boulder. By examining lake sediments from the Colombian Andes, researchers have found that during periods millions of years ago when carbon dioxide levels were similar to today’s, tropical land heated up nearly twice as much as the ocean.

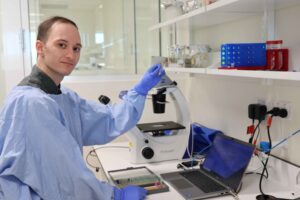

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provides crucial insights into how tropical regions could respond to ongoing climate change. Lead author Lina Pérez-Angel, who conducted the study as a doctoral student at CU Boulder’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) and the Department of Geological Sciences, emphasized the importance of understanding regional climate changes. “The tropics are home to about 40% of the world’s population, yet we’ve had very little direct evidence of how tropical land temperatures respond to climate change,” she noted.

Climate Archive from Sediments

Approximately 2.5 to 5 million years ago, during the Pliocene epoch, Earth was significantly warmer, and Greenland was largely ice-free. This period serves as a vital analog for current climate conditions due to similar carbon dioxide levels. Sediment cores, which accumulate chemical signals, fossils, and minerals over time, are essential tools for reconstructing past climates. They provide a window into historical temperature, rainfall, and atmospheric conditions.

Most existing knowledge about ancient temperatures comes from ocean cores, as seafloor sediments are less disturbed by geological changes. However, in 1988, a team of Dutch and Colombian scientists retrieved a 580-meter long sediment core from the Bogotá basin in Colombia. This region, located at nearly 2,550 meters above sea level, has preserved sediment continuously since the late Pliocene.

Pérez-Angel and her team analyzed bacterial fats preserved in the core to reconstruct a temperature record from the Pliocene to the Pleistocene, or Ice Age. Their findings revealed that the tropical Andes were about 3.7 °C warmer than today, while the tropical sea surface was only 1.9 °C warmer. This indicates that land temperatures in the tropics changed from about 1.6 to nearly 2.0 times more than the tropical ocean.

Feedback Loop and Modern Implications

According to Pérez-Angel, now a senior research associate at Brown University, the Pacific Ocean experienced nearly permanent El Niño conditions during the late Pliocene, which further heated the tropical Andes. Modern El Niño events already cause significant warming and drought in the northern Andes, and the research team warns that climate change could increase the frequency of such events.

“If you compare the temperature records for the past couple of decades with what climate models predicted a few decades ago, you see that all the real-world data is at the uppermost end of those predictions,” said Julio Sepúlveda, senior author and associate professor in the Department of Geological Science. “This is partly because there are so many feedback mechanisms in nature, and crossing certain thresholds could trigger a series of cascading events that amplify changes.”

Overlooked Tropical Regions

Pérez-Angel pointed out that tropical regions often receive less attention in climate science, partly because leading research institutions are located in higher latitude areas like North America and Europe. Additionally, while the tropics are not warming as rapidly as colder regions, such as Greenland or Antarctica, any temperature increase in already hot areas could exceed the limits of human and wildlife tolerance.

“When we model climate change, we tend to focus on how temperatures are going to change globally. But people experience climate change at the regional level,” Pérez-Angel explained. With limited resources in many tropical communities, understanding future climate scenarios is crucial for building resilience.

The study underscores the need for more regional climate research to better prepare and adapt to the potential impacts of climate change, particularly in vulnerable tropical areas.