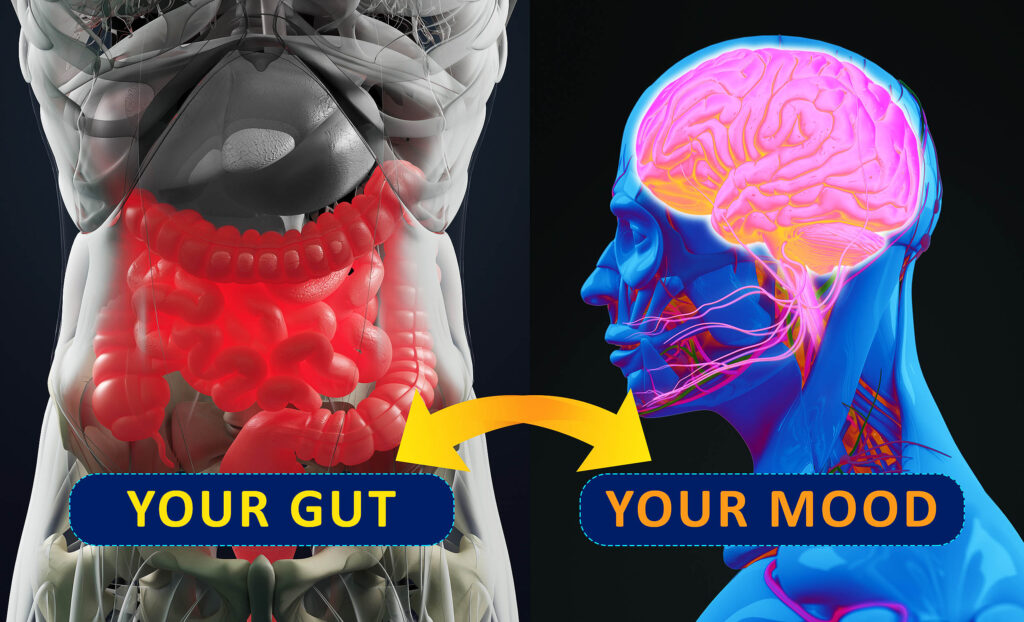

Gut-brain connection or gut brain axis. Concept art showing a connection from the gut, influencing your mood. 3d illustration.

Scientists have long understood that the stomach, gut, and brain are in constant communication. However, new research suggests that this dialogue may not always be beneficial. A significant study involving over 200 adults has revealed that when the stomach’s natural rhythm becomes too synchronized with brain activity, it correlates with higher levels of anxiety, depression, and stress, leading to a decrease in overall wellbeing.

The findings from this research, which involved recordings from both the brain and stomach, highlight specific control networks in the brain where this coupling is most pronounced. Rather than signaling resilience, this pattern appears to reflect a system under psychological strain.

When Stomach-Brain Sync Goes Wrong

Lead author Leah Banellis and senior author Micah Allen, both from Aarhus University’s Department of Clinical Medicine, spearheaded this research. Their team concentrated on the stomach’s rhythm rather than gut microbes. “The stomach’s connection to the brain may actually be too strong in people under psychological strain,” Banellis noted, suggesting that this body signal might indicate distress.

Allen added, “Intuitively, we assume stronger body-brain communication is a sign of health. But here, unusually strong stomach-brain coupling seems linked to greater psychological burden, perhaps a system under strain.” The study found that coupling in the frontoparietal regions, rather than the primary sensory cortex, was associated with worse mental health across multiple symptoms, distinguishing this signal from general data noise.

Stomach Rhythm and Brain Activity

The stomach houses the enteric nervous system, a vast neural network that can independently manage digestion while communicating bidirectionally with the central nervous system. Often referred to as the body’s “second brain,” its intrinsic electrical rhythm runs about three cycles per minute in healthy adults, setting an upper limit on stomach contractions.

This rhythm is generated by specialized pacemaker cells known as the interstitial cells of Cajal. Disruption in this system can affect motility and timing. Previous brain mapping studies have shown that sensory and motor cortices align with the stomach’s rhythm during rest, establishing a baseline of brain-stomach coherence. The new study from Aarhus extends this baseline to include mental health and overall wellbeing.

Stomach Signals and Mood Changes

The stomach communicates with the brain through various channels, with the vagus nerve being the most direct. It conveys sensory information about stomach stretching, the chemical environment, and muscle activity to brainstem regions, influencing mood-regulating networks. Signals also travel via hormonal and immune pathways, with gut hormones and inflammatory molecules affecting brain function over time.

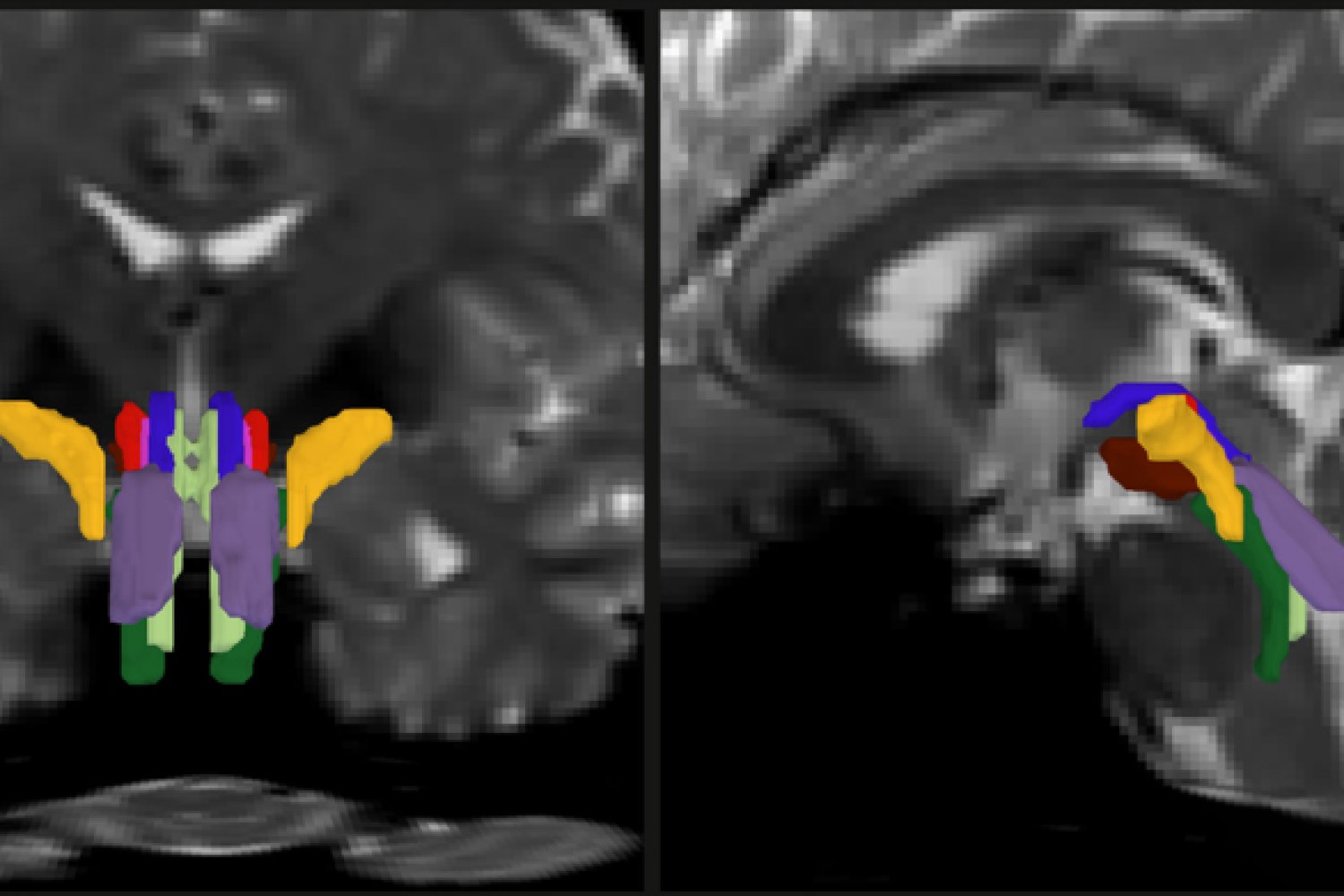

This creates a feedback loop where the brain can modulate stomach activity, and the stomach can influence brain states. The research team combined functional MRI with surface electrogastrography, a noninvasive method that records stomach electrical activity using electrodes placed on the abdomen. Aligning these signals allowed scientists to quantify stomach-brain coherence within individuals.

How the Rhythm Was Measured

The researchers related regional coupling values to symptom dimensions such as anxiety, depression, stress, and well-being. Cross-validated models helped reduce overfitting and increased generalizability. Coupling strength varied across the cortex, with control regions carrying most of the mental health signal, arguing against a diffuse, gut-wide effect.

This approach builds on previous work that identified a “gastric network” at rest, defined by delayed connectivity between the stomach’s slow wave and cortical activity, providing the physiological basis for the current analysis.

Stomach Waves as Mental Health Indicators

Clinical tools often rely on self-reporting, so an objective physiological marker could help track risk or monitor responses. Pairing symptoms with a body-based index might sharpen assessments. “We know certain medications – and even the foods we eat – can influence gastric rhythms,” Allen stated. “One day, this research might help us tailor treatments based on how a patient’s body and brain interact, not just what they report feeling.”

Evidence already shows that noninvasive stimulation of the vagus nerve can enhance stomach-brain coupling within minutes in healthy adults. This tool could help test whether changing coupling affects symptoms. Conceptual work also frames vagal pathways as mechanisms for switching between survival modes and shaping goal-directed behavior, highly relevant to mood and motivation. Translational studies can build on these ideas to develop interventions.

From Signatures to Interventions

The present study is cross-sectional and correlational, so it cannot definitively show that stomach waves drive anxiety or depression. However, it maps an objective signature that warrants further investigation. Future trials can test whether modulating stomach rhythms, adjusting activity in frontoparietal nodes, or tuning vagal signaling alters symptoms in clinical populations.

Predictive use cases, like early warning of relapse, are within reach. Open materials listed in the paper should support independent checks and faster progress. Shared data and code encourage cumulative science. Clear next steps include replication in older adults, richer sampling across diagnoses, and longitudinal designs that track coupling alongside treatment. Precision targets will depend on which levels of the axis prove most malleable.

The study is published in Nature Mental Health.

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates. Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.