Scars are a common aftermath of injuries, surgeries, or burns, often leading to concerns about their appearance. However, scars can have more profound implications beyond the surface, affecting tissue flexibility, organ function, and sometimes causing chronic pain. Surprisingly, internal scarring, or fibrosis, can be fatal, contributing to approximately 45% of deaths in the United States, particularly when vital organs like the lungs, liver, or heart are involved.

Scarring is not merely a cosmetic issue. Scarred skin is stiffer and weaker than normal skin, lacking sweat glands or hair follicles, which impairs the body’s ability to regulate temperature. This can be particularly problematic during hot weather, fevers, or recovery from significant injuries. Additionally, scar tissue can thicken, tighten, or continue to remodel over time, complicating recovery further.

Why Facial Wounds Heal Differently

Doctors have long observed that facial wounds tend to heal with less scarring compared to injuries on other body parts. This phenomenon suggests that the body employs different repair strategies depending on the injury’s location. Dr. Michael Longaker explains, “The face is the prime real estate of the body. We need to see and hear and breathe and eat. In contrast, injuries on the body must heal quickly. The resulting scar may not look or function like normal tissue, but you will likely still survive to procreate.”

A recent study from Stanford Medicine has delved into this mystery, revealing potential methods to minimize scarring and enhance genuine tissue repair. The research indicates that modifying ancient healing patterns could help prevent scars after surgery or trauma and possibly treat existing scars.

Insights from the Stanford Study

Dr. Derrick Wan highlights the developmental uniqueness of the face and scalp, noting that tissue from these areas originates from neural crest cells in the early embryo. “In this study, we identified specific healing pathways in scar-forming cells called fibroblasts that originate from the neural crest and found that they drive a more regenerative type of healing,” Wan stated.

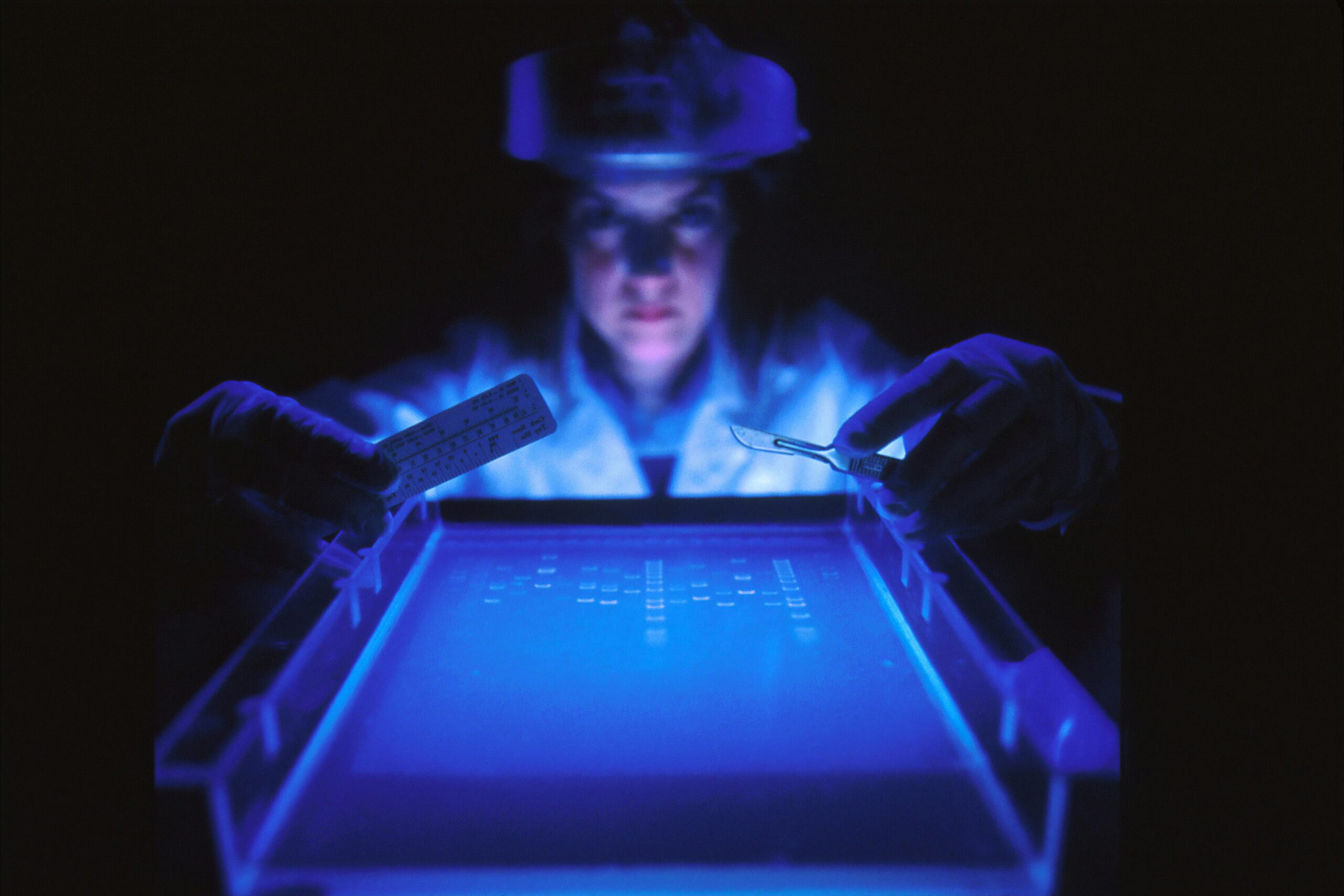

To explore healing differences, researchers created small skin wounds on the face, scalp, back, and abdomen of lab mice. They ensured the mice were anesthetized, provided pain relief, and stabilized the wounds to prevent movement from affecting the results. After 14 days, face and scalp wounds exhibited lower levels of proteins associated with scar formation, resulting in smaller scars.

Transplant Experiments and Key Findings

The researchers conducted innovative experiments by transplanting facial skin onto the backs of other mice and repeating the wound experiment. Remarkably, the transplanted skin retained its original healing properties, showing reduced scarring. Additionally, when fibroblasts from different body sites were injected into mice, those from facial skin resulted in lower levels of scarring-related proteins compared to fibroblasts from other areas.

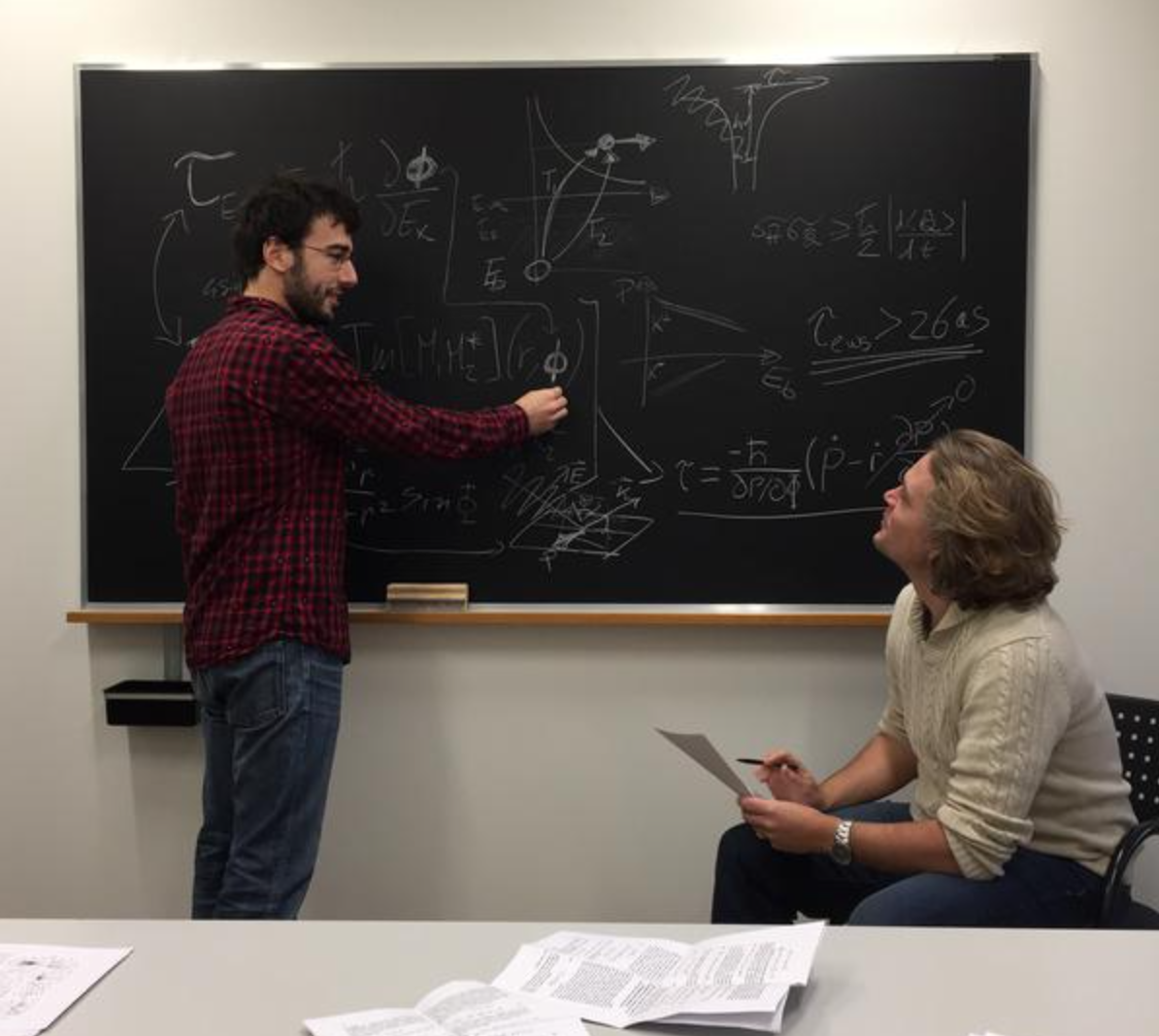

“Many of the authors on this paper are fellow physician scientists,” said Dr. Dayan J. Li. “This project was inspired by what we’ve observed in our patients – facial wounds in general heal with less scarring. We wanted to understand, mechanistically, why this is.”

One of the most striking results was the minimal number of cells required to alter healing. The team discovered that even when altered fibroblasts comprised a small fraction of the cells near a wound, the healing pattern shifted towards less scarring.

Proteins and Gene Expression

The scientists traced this effect to a signaling pathway involving a protein called ROBO2. In facial fibroblasts, ROBO2 helps maintain a less-fibrotic state. They found that ROBO2-positive fibroblasts had DNA that was generally less transcriptionally active, meaning it was less available for proteins to bind and activate genes.

“In general, the DNA of the ROBO2-positive cells is less transcriptionally active, or less available for binding by proteins required for gene expression,” Li explained. “These fibroblasts more closely resemble their progenitors, the neural crest cells, and they might be more able to become the many cell types required for skin regeneration.”

Potential Drug Targets and Future Implications

The pathway extends beyond ROBO2, connecting to EP300, a protein that facilitates gene activation. In fibroblasts prone to scarring, EP300 activity supports gene expression leading to fibrosis. The team found that inhibiting EP300 activity with a pre-existing small molecule made back wounds heal more like facial wounds.

“It seems that, in order to scar, the cells must be able to express these pro-fibrotic genes,” Longaker said. “And this is the default pathway for much of the body.”

Given that EP300 is already under study in cancer research, existing clinical trials for small molecule inhibitors could expedite the development of therapies to improve wound healing. Dr. Wan suggests that understanding these pathways could enhance healing after surgeries or trauma, potentially extending to internal scarring as well.

Dr. Longaker anticipates that the findings could lead to a unifying approach to treating or preventing scarring across different tissue types. “There’s not a million ways to form a scar. This and previous findings in my lab suggest there are common mechanisms and culprits regardless of the tissue type, and they strongly suggest there is a unifying way to treat or prevent scarring,” he concluded.

The full study was published in the journal Cell.

—

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.