The world economy has been on a path of increasing integration for nearly four centuries, a journey that even two world wars could not entirely derail. This long march of globalization was fueled by rapidly increasing levels of international trade and investment, vast movements of people across borders, and dramatic changes in transportation and communication technology.

According to economic historian J. Bradford DeLong, the value of the world economy (measured at fixed 1990 prices) rose from US$81.7 billion (£61.5 billion) in 1650 to US$70.3 trillion (£53 trillion) in 2020—an 860-fold increase. The most intensive periods of growth corresponded with the “long 19th century” and the post-World War II era, up to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Now, however, this grand project appears to be on the retreat. While globalization is not dead, it is certainly ailing. This shift raises the question: is this a cause for celebration or concern? As a longtime BBC economics correspondent, I believe there are historical reasons to worry about a deglobalized future, even beyond the tenure of Donald Trump and his disruptive tariffs.

The Historical Context of Globalization

The announcement comes as the world reflects on the historical context of globalization. In each era since the mid-17th century, a single country has sought to be the global leader, shaping the rules of the economy. These hegemonic powers had the military, political, and financial strength to enforce these rules and convince other nations of their path to wealth and power.

However, as the U.S. under Trump slips into isolationism, no other power seems ready to take its place. China, often seen as a potential successor, faces significant economic challenges, including the lack of a truly international currency and the absence of a democratic mandate.

The French Model: Mercantilism and Its Legacy

By the mid-1600s, France had emerged as Europe’s strongest power, developing the first overarching theory of how the global economy could work in its favor. This mercantilist approach, revived in some aspects by Trump’s policies, emphasized trade barriers to limit imports while boosting domestic industries.

France’s finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, systematically applied mercantilism across government policy, believing that trade would strengthen France’s economy while weakening its rivals. Under Colbert, France pioneered protectionism, tripling import tariffs and strengthening domestic industries through subsidies and monopolies.

Despite initial successes, France’s state-run companies could not compete with the commercially driven Dutch and British East India companies. Ultimately, France’s mercantilist policies led to endless wars and economic retaliation, a cautionary tale for modern protectionist policies.

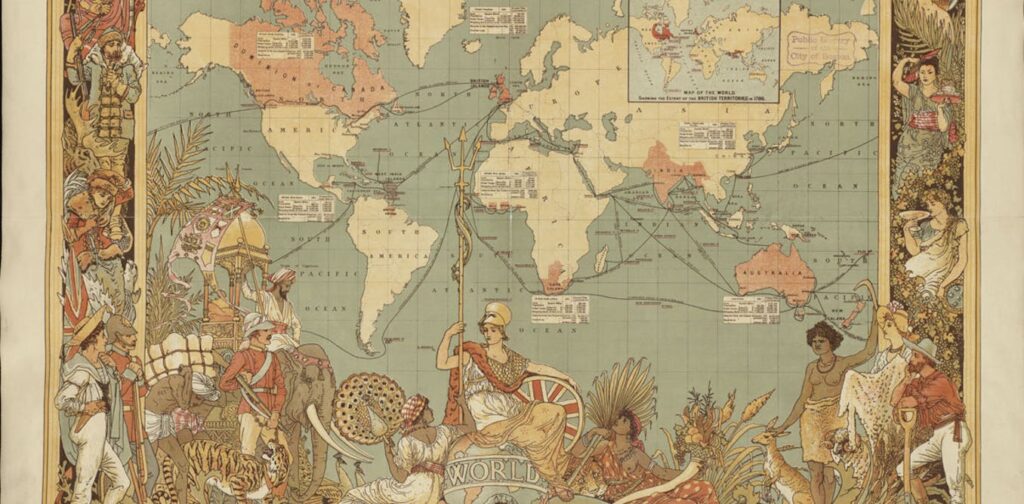

The British Model: Free Trade and Empire

Meanwhile, Britain embraced the ideology of free trade, articulated by economists Adam Smith and David Ricardo. They argued that trade was not a zero-sum game, as mercantilists believed, but that all countries could mutually benefit.

As the world’s first industrial nation, Britain created an economic powerhouse based on steam power, the factory system, and railroads. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 signaled a shift of power to the manufacturing classes, unleashing the power of British manufacturing to dominate global markets.

Britain’s commitment to free trade, coupled with the rise of the City of London as a financial center, allowed it to dominate the world economy. However, this era of globalization was marked by the domination of a few rich European powers, often at the expense of global economic development.

The American Model: From Protectionism to Neoliberalism

While Britain enjoyed its century of global dominance, the United States embraced protectionism for longer than any other major Western economy. Tariffs protected emerging U.S. industries, and by the late 19th century, the U.S. was the world’s largest steel producer.

After World War II, the U.S. assumed the role of global superpower, focusing on creating global organizations to establish binding regulations and open markets to American trade and investment. The U.S. dollar became the global medium of exchange, cementing U.S. financial dominance.

However, by the 1970s, the U.S. economy faced increasing pressure from German and Japanese rivals. The end of the gold standard and the rise of financialization led to a series of financial crises, culminating in the 2008 global financial crisis.

The Trump Era: A Return to Mercantilism

Trump’s presidency marked a return to mercantilist views, with high tariffs and a repudiation of international agreements. His policies have increased inequality and threatened the U.S.’s economic credibility.

While Trump highlighted some of the ills of the U.S. economy, his policies are rapidly squandering the goodwill built up in the postwar years. Even without Trump’s disruptions, the end of the U.S. era of hegemonic dominance would still have occurred.

The Future of Globalization

Globalization is not dead, but it is dying. The troubling question we face is what happens next. As the world navigates this uncertain future, the lessons of history provide valuable insights into the potential consequences of a deglobalized world.

This is the first of a two-part series on the rise and fall of globalization. Stay tuned for part two, which will explore why the next global financial meltdown could be much worse with the U.S. on the sidelines.