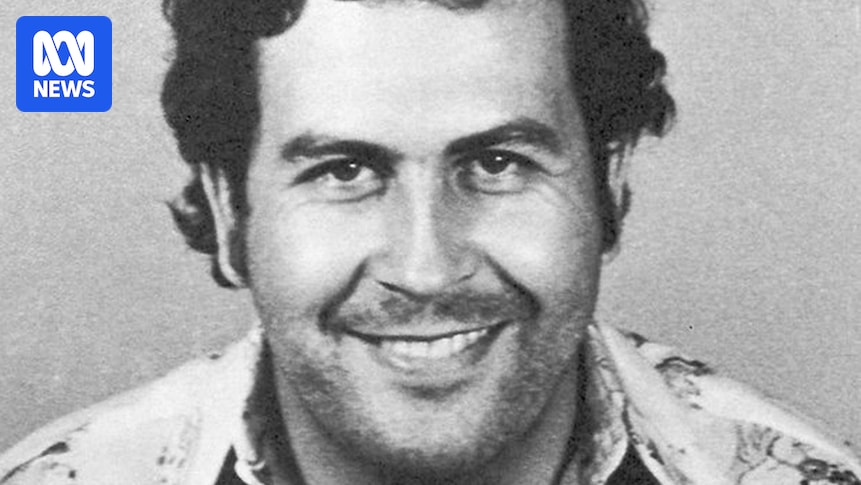

It was early afternoon in mid-summer, December 2, 1993, when notorious cartel boss and narcoterrorist Pablo Escobar made a fateful phone call to his son. The air was dry and warm over Colombia, and the sky was clear, but Escobar’s world was anything but serene. For the past year, he had become increasingly isolated as his cocaine empire crumbled around him. Living in a safe house in Los Olivos, a suburb of Medellín, Escobar was a fugitive in the city where he once ruled supreme.

The two-storey row house he occupied was deliberately nondescript, blending into the neighborhood with its red-tiled roof and stucco walls. It was a stark contrast to the luxury he once enjoyed at La Catedral, a self-built prison where he lived under house arrest following a 1991 surrender deal with the Colombian government. The agreement was supposed to keep him out of U.S. hands in exchange for a promise to cease his drug operations. However, the arrangement quickly fell apart as Escobar continued to run his empire from behind bars.

The Escape and the Hunt

Escobar’s escape from La Catedral in 1992 marked the beginning of a relentless manhunt. The Colombian National Police’s Search Bloc, a special unit created solely to capture him, was closing in. The Search Bloc’s mission was clear: dismantle the Medellín Cartel, which at its peak controlled 80 percent of the cocaine trade to the United States.

Escobar’s criminal activities extended far beyond drug trafficking. His cartel was implicated in widespread corruption and violence, including the assassinations of judges, politicians, and even a presidential candidate. The Colombian government, under immense pressure to restore law and order, was determined to bring him down.

“At its height, Escobar’s drug business was said to earn more than $30 billion a year.”

The Final Mistake

On the day of his last phone call, Escobar was forced to rotate between a series of humble hideouts, constantly on guard. The call to his son, Juan, then 16, proved to be his undoing. Using radio triangulation, the Search Bloc pinpointed the call’s origin, setting the stage for a dramatic showdown.

As police closed in, Escobar and his bodyguard, Alvaro de Jesus Agudelo, known as El Limon, attempted to flee. They ran to the second floor, planning to escape across the rooftops of Medellín’s densely packed streets—a tactic that had worked for Escobar before. But this time, the police were ready.

A gunfight erupted on the roof. El Limon was killed first, and soon after, Escobar was shot in the leg and torso. A bullet to the head ended the life of the man who had once been the most powerful drug lord in the world. While Colombian police claimed the fatal shot, Escobar’s son later suggested his father took his own life, choosing death over capture.

The Aftermath and Legacy

Escobar’s death was met with mixed reactions. For the Colombian government and the United States, it marked a significant victory in the war against drugs. Many Colombians celebrated in the streets, relieved at the end of the Medellín Cartel’s reign of terror.

However, in Medellín’s poorest neighborhoods, Escobar was seen in a different light. To some, he was a Robin Hood figure, revered for funding social programs and building schools and houses. This dual legacy continues to shape perceptions of Escobar even today.

“More than three decades after his death, Escobar’s legacy continues to impact Colombia.”

Escobar’s story remains a subject of fascination, with tourists flocking to see where he lived and died. His life has been immortalized in TV series, books, and even video games. Yet, his most enduring legacy is perhaps the cautionary tale it provides about the devastating costs of a life of crime and violence.

As Colombia continues to grapple with the remnants of Escobar’s empire, the story of his rise and fall serves as a reminder of the complex interplay between power, corruption, and the human cost of the drug trade.