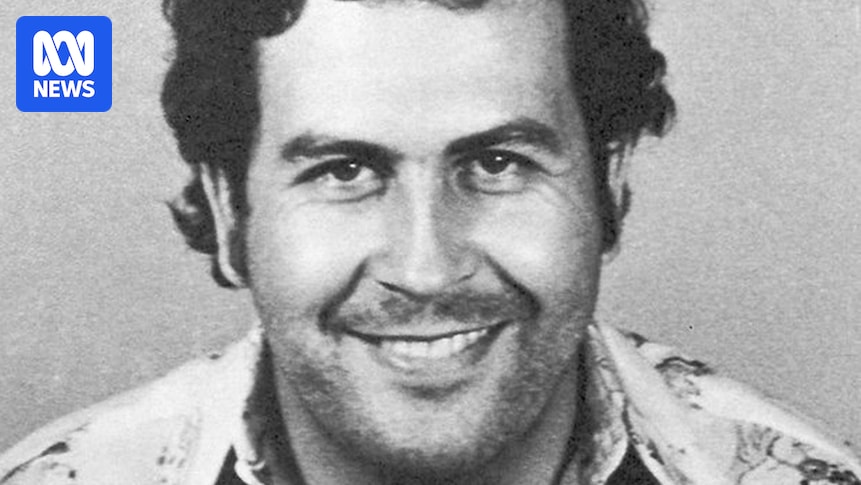

It was early afternoon in mid-summer, with the dry, warm air hanging over Colombia. The sky was clear as notorious cartel boss and narcoterrorist Pablo Escobar picked up the phone to call his son. The date was December 2, 1993. For the past 12 months, Escobar had become increasingly isolated as his cocaine empire began to crumble. He was living in a safe house in Los Olivos, a suburb of Medellín not far from where he had grown up, under a false name.

This nondescript two-storey row house, with its red-tiled roof and stucco walls, blended into the neighborhood, a perfect hideout for a man on the run. A year earlier, Escobar had escaped from his luxurious prison home, La Catedral, a self-built opulent detention center where he lived under house arrest as part of a 1991 surrender deal. He was supposed to serve five years and had promised to trade his drug business for his freedom. In return, the Colombian government agreed not to extradite him to the US.

However, Escobar continued to run his drug operations unhindered from La Catedral. The deal with the Colombian government collapsed, and Escobar was once again a wanted man. The plan was to arrest him and shift him to a conventional prison to serve his term. But Escobar had other plans.

The Final Mistake

On the day Escobar called his son, he had been on the run for 12 months, rotating between a series of humble and low-profile homes, constantly on guard, constantly evading capture. Known by his pseudonyms El Patron, El Doctor, and El Zar de la Cocaina, the King of Cocaine knew he was being hunted.

The Colombian National Police’s Search Bloc had him at the top of their Most Wanted list. The rival Cali Cartel had assassins on call, and a vigilante group supported by US intelligence, Los Pepes — The People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar — also wanted him dead. Everything was about to come crashing down. The phone call to his son Juan, then 16, was Escobar’s final mistake.

At its peak, Escobar’s Medellín Cartel controlled 80% of the cocaine trade to the United States, earning more than $30 billion a year.

Escobar began smuggling contraband into the US in the early 1970s. By 1976, he had founded the cartel and smuggled tonnes of cocaine each week through the region and into the US and Canada. His crime business was implicated in widespread corruption and violence across Colombia, including assassinations of judges, politicians, and police officers, and even the 1989 presidential candidate, Luis Carlos Galán. The cartel bombed an airliner and kidnapped officials and Colombia’s wealthy.

Luck Runs Out

That day, the task force swung into action, using radio triangulation to pinpoint the exact location of the call to his son. The Search Bloc had set up radio equipment across Medellín and measured the direction of Escobar’s call from several locations. The intersection marked the spot where the call was being made, and Escobar could be found.

As the Colombian police closed in, Escobar’s bodyguard, Alvaro de Jesus Agudelo — known as El Limon, The Lemon — realized the pair had been found. Rather than surrender, they ran to the second floor of the safe house, planning to escape through a window and onto the roof. Running from one roof to the next in Medellín’s closely packed streets was a strategy Escobar knew well. He had escaped across rooftops before, planning to lose the police by disappearing into the densely built neighborhood.

But this time was different. Police followed Escobar and El Limon onto the roof, and a gunfight broke out. El Limon was killed first, and soon after, Escobar was shot in the leg and torso. It was a bullet to the head that killed Escobar. Colombian police claimed they shot the crime boss. Escobar’s son, Juan, who has since changed his name and works as an architect, has a different story. He has said his father — surrounded and with no means of escape — ended his own life.

Pablo Escobar, notorious leader of Colombia’s Medellín Cartel, was dead at 44.

Legacy and Consequences

While some responses to the death of the King of Cocaine were predictable — relief from the Colombian government, which saw his death as marking the end of the Medellín Cartel’s reign of terror, and in the US, a victory in the war against drugs — not everyone was pleased to see Escobar gone. When Escobar’s death was announced, many Colombians celebrated in the streets. But in Medellín’s poorest neighborhoods, the reaction was very different. Some saw him as a Robin Hood figure and revered him for funding social programs, donating money to needy families, and building schools and houses.

More than three decades after his death, Escobar’s legacy continues to impact Colombia. Fascination with his life persists. Tourists join tours to see where he lived and died, and TV series, books, merchandise, video games, and museums have all commemorated and even celebrated his life of crime.

Escobar’s greatest legacy is often seen as the warning it offers about the cost of drugs and the price of a life of violence.

The fall of Pablo Escobar marked a significant turning point in Colombia’s history, highlighting the complex interplay between crime, politics, and society. As the country continues to grapple with the remnants of Escobar’s empire, the lessons of his rise and fall remain relevant in the ongoing battle against drug trafficking and organized crime.