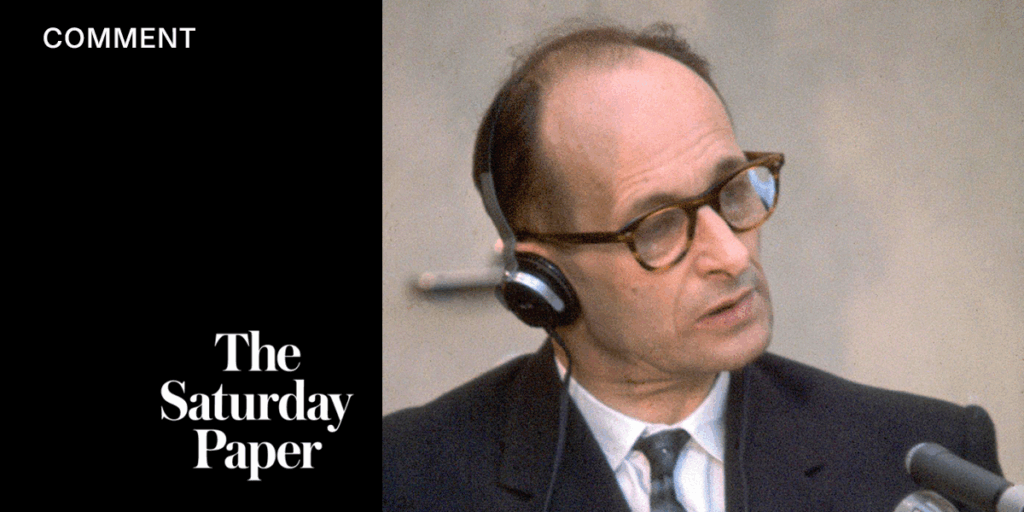

This week, I watched The Eichmann Trial, a documentary edited from thousands of hours of footage of the Nazi war criminal’s “trial of the century,” held in Israel in 1961. It was during this trial that Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe the bureaucratic nature of Adolf Eichmann’s actions. However, I have always found this formulation unconvincing. Arendt seemed to reduce malevolent evil to the level of a factory accident, turning the devil into a mere office clerk.

Yet, watching Eichmann testify, there was something disembodied about him, especially when he offered his “apology” to the Jewish people after receiving the death sentence. What struck me was the reaction of people interviewed at the time. While most welcomed the sentence, some believed justice would be better served if Eichmann were to live the rest of his days in the hell of his own conscience. Even more surprising were those who preferred no trial at all, wishing the Shoah to be consigned to the cold storage of history.

The Elusive Concept of Justice

The question of justice troubled me deeply. There seems to be no adequate justice for the horrors humans inflict upon one another. Eichmann was punished, but was that truly justice? Who am I to say what could ever atone for the Holocaust? Watching the film in 2025, in the shadow of the horror of October 7, 2023, and the subsequent devastation in Gaza, the question of justice remains pertinent.

I come from my own hard history. First Nations people continue to search for truth and reconciliation, yet I find this unsatisfying. History is not a place of truth or healing, and certainly not of justice. As James Joyce paraphrased, history is a nightmare from which we are trying to awake.

Forgiveness: A Path to Sovereignty?

One word missing from the documentary, and from Australian truth-telling, is forgiveness. Yet, forgiveness is a word that would undoubtedly taste sour in the mouths of Palestinians today. People naturally want justice or, worse, vengeance. These two are inseparable and can beget the very cruelty they seek to punish. Justice, as Albert Camus saw it, is always an invitation to hate.

For me, forgiveness is the highest form of sovereignty. It is the ultimate measurement of what it is to be human. Forgiveness sets aside justice, eschews vengeance, and disavows resentment. It is divine, while we are sadly profane. We often entomb our children in the cave of memory rather than allow them to walk in the light of forgiveness. “Never forget” is our mantra; history is the iron in the bloodstream of identity.

Miroslav Volf urges us to “remember rightly.” We must remember as God remembers, where wounds are borne by God, who drives out the darkness.

Volf turns the question of forgiveness to a “non-remembrance,” suggesting that our identity no longer comes from our past but from a forgiving God. Forgiveness is essential for human wholeness, or as Nietzsche warns, the past becomes “the gravedigger of the present.”

The Philosophical Debate on Forgiveness

How do we even begin to forgive? The French philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch argues that forgiveness is not an act or absolution. We cannot forgive conditionally or expect anything in return. Forgiveness requires a real human connection—a relationship with each other. That’s what is missing in a courtroom where the process is served, but justice is not.

Eichmann simply shuffled his papers, collected himself, and exited the court without emotion. The process was served, but it was not justice. Eichmann died, and his abomination with him, yet it doesn’t truly die. We are left with it. Then what?

Jean Améry, a Holocaust survivor, refused to forget what he had seen. He railed against “the hollow, thoughtless, utterly false conciliatoriness or the pathos of forgiveness and reconciliation.”

Améry saw resentment as a virtue, a duty. It took its toll, and at 65, he took his own life. While there is much to admire in Améry’s stance, I reject it because of where it ends. I choose life and forgiveness, which Jankélévitch calls supernatural, an act of grace.

The Challenge and Necessity of Forgiveness

Forgiveness must be spontaneous. We can remain horrified at the actions of the guilty person, yet transform our relationship with that same human being, transfiguring hatred into love. Not easy, is it? That’s what makes thinkers like Jankélévitch so important. He doesn’t play it safe or seek to feed the blood lust of the crowd.

Jankélévitch says, “There is nothing unforgivable. Forgiveness is absurd, it is unjust. Such is the miracle.”

We don’t live in an age of miracles. We keep score, and trauma is currency. Our wounds are family heirlooms. History is the God we worship, which might be okay if it made us whole, but it doesn’t. It didn’t at the Eichmann trial in 1961, and it doesn’t now.

Each child born should be a tabula rasa, a chance to write history anew. Instead, their fate is foretold. Our historical blood feuds call us into battle. We are encouraged to live big, heroic lives, avenging ancestral crimes. I’m more inclined to Marcus Aurelius: “Each man lives only in the present moment.”

Forgiveness is such a small act. No army marches for forgiveness. There are no medals for forgiveness. No politician is elected today promising forgiveness. As I said, who am I to tell anyone how to live with the crimes committed against their own? I invite derision even talking about forgiveness. I’m certainly open to accusations of hypocrisy; I admit I struggle at times to quell an unfathomable rage.

I recognize forgiveness is a hard, lonely road, one I have chosen to walk with the likes of Miroslav Volf and Vladimir Jankélévitch. Two thousand years ago, a poor carpenter said forgiveness is a cross on which we must be willing to die. It is also the cross for which we must live.

To quote Jankélévitch, “forgiveness extends to infinity.”