Michael Caton, a beloved Australian actor, enjoys the convenience of living just a short stroll from Sydney’s iconic Bondi Beach. However, when he needs to travel into the city, he knows better than to schedule anything before late morning, well after the peak hour rush. “You wouldn’t dream of taking the bus in the morning,” the 82-year-old remarks while driving his Toyota RAV4. “They’re all full. They just don’t really do the job.”

Caton, famous for his role as Darryl Kerrigan in the classic film The Castle, has a history of speaking out against impractical dreams. In 1998, he led a campaign against a proposal to extend Sydney’s Eastern Suburbs railway line from Bondi Junction to the beach, warning it would be “the end of the line for Bondi.”

Despite Sydney boasting Australia’s busiest rail network, catching a train to the beach remains a distant dream. Unlike cities such as Rio de Janeiro and New York, where beaches are easily accessible by train, Sydney’s famous beaches like Bondi and Manly remain largely unreachable by rail.

The Historical Context of Sydney’s Rail Network

Sydney’s rail network has a storied past, initially developed to transport agricultural products from rural areas into the city. Dr. Geoffrey Clifton, a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney, explains that heavy rail lines gradually expanded alongside the city’s growth. By the late 1800s, trams emerged as a popular alternative, particularly in the eastern suburbs where distances were shorter.

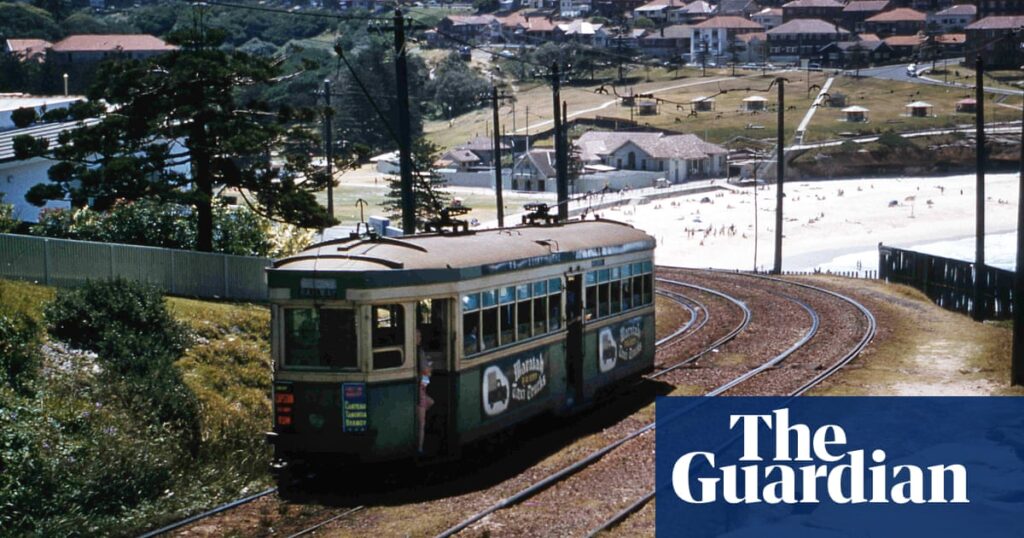

“Trams made more sense in the east of Sydney,” Clifton notes. However, political interests in the western suburbs favored heavy rail, leading to a competition between the two modes of transport. Sydney eventually developed one of the largest tram networks globally, with services that were faster than many modern lines.

“Shoot through like a Bondi tram” became a popular expression, reflecting the speed and efficiency of the tram services.

However, the rise of the automobile post-World War I and II led to the decline of trams. Returning soldiers bought bus licenses, spurring suburban development away from tram lines. The tram network, in need of investment, was dismantled in favor of buses, a decision now criticized by transport experts like Mathew Hounsell from the University of Technology Sydney.

Decades of Unfulfilled Proposals

Since the closure of Sydney’s original tram network in 1961, numerous proposals for new train lines to beachside suburbs have surfaced, only to be thwarted by local opposition and logistical challenges. A 1970s plan for a heavy rail line to the northern beaches was abandoned due to these hurdles.

Efforts to extend rail through the eastern suburbs, including the Bondi beach proposal Caton opposed, have similarly faltered. The Eastern Suburbs line to Bondi Junction remains a rare post-tram era rail project, with plans to extend it further never realized.

Resistance from established communities has been a significant barrier. In Woollahra, a partially constructed station on the Eastern Suburbs line was left incomplete due to resident objections. This resistance reflects a broader “nimby” (not in my backyard) sentiment that complicates infrastructure development.

“A lot of the problem with why these proposals go nowhere is because these suburbs are already well developed,” Clifton explains.

Current Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite the absence of a train station, Bondi Beach continues to draw crowds, exacerbating traffic and parking issues. The 333 bus route, connecting the city to Bondi, is one of Sydney’s busiest, with annual ridership exceeding 8 million.

Caton, despite his frustrations with crowded buses, stands by his opposition to the rail extension, arguing it offered little benefit to locals. “The train did absolutely nothing for the locals,” he insists, highlighting the lack of additional stations along Bondi Road.

As Sydney grapples with these challenges, the current New South Wales government’s focus on transport-oriented development offers a glimmer of hope. Clifton suggests extending light rail from Randwick to Coogee Beach and Kingsford to Maroubra Beach as plausible options, contingent on local support.

“If local communities want that, they should be developing plans and … advocating to government for those extensions,” Clifton advises.

While extending light rail presents logistical challenges, future projects may focus on driverless metro trains. The NSW government is considering eastern extensions of the Sydney Metro West line, potentially connecting the CBD to Maroubra and Malabar.

For now, Sydney’s beachgoers must rely on buses and cars, navigating the city’s congested roads. The dream of catching a train to the beach remains just that—a dream, for now.