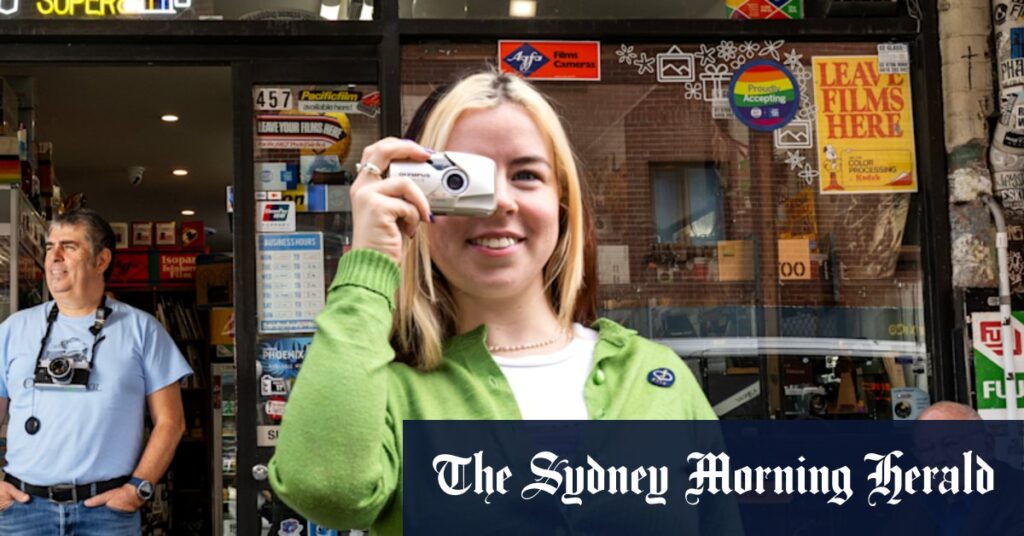

If Sydney Super8 had a shopkeeper’s doorbell on a Friday afternoon, it would be ringing constantly with the steady stream of young people coming and going. The old-school film and camera shop is considered an institution in Newtown, with passing pedestrians getting a peek inside the bright Kodak-yellow exterior.

More often than not, it’s millennials and Gen Z who occupy the narrow shop space, dropping off single-use cameras for processing, buying rolls of film from the fridge, or asking technical questions of current owner Nick Vlahadamis and former owner (and now worker) Christopher Tiffany. While some things have not changed, others have.

“Our customers are 90 per cent young people and maybe 75 per cent of the time they are female,” says Tiffany. “You get half a dozen girls at the table outside going through their pictures, giggling, laughing and carrying on like crazy.”

Vlahadamis notes that the store has attracted a younger crowd since it opened in its current spot in 2013, with a noticeable increase after the pandemic. “Social media has an impact, it’s really weird, [that] digital social media has an impact on an old technology. I think the same thing happened with records,” he adds.

The Analog Appeal

Twenty-six-year-old Lilly Orrell, a regular at Sydney Super8, was seen dropping her camera for repair, a Pentax Espio she received on her 21st birthday. Orrell shoots on film for fun and because it looks “cute.” She brings her film camera on nights out, to capture candid moments with friends and on holidays, like her recent trip to Europe.

“It captures the moment, you can’t be like ‘I look ugly’ and re-take it… The photo is what it is,” says Orrell, who has been on a break from Instagram due to the pressure to capture and share a ‘perfect’ moment.

Orrell’s sentiment reflects a broader cultural shift among younger generations who are increasingly drawn to the authenticity and nostalgia of analog media. This trend is reminiscent of the resurgence of vinyl records, where the tactile experience and imperfections are part of the allure.

Industry Challenges and Innovations

In August, photography company Eastman Kodak reported its quarterly filings, including significant debt, which sparked rumors of potential closure. Kodak swiftly addressed these reports, stating that “Kodak has no plans to cease operations” and is “confident it will repay, extend, or refinance its debt.”

Meanwhile, the iconic 133-year-old company temporarily paused its film production in November 2024 to upgrade its New York factory facilities, aiming to meet the growing demand for motion picture and still image film.

Japanese camera manufacturer Pentax made headlines last year with the launch of the Pentax 17, the first new film camera from a major brand since the 2000s. “It’s a camera that shouldn’t exist today. They have almost sold out globally. But as a major manufacturer, Pentax has gone out on a limb,” comments Vlahadamis.

FujiFilm Australia also took a bold step by re-launching QuickSnap, a 35mm single-use camera, targeting Gen-Z customers. FujiFilm Australia’s general manager Mary Georgievski explains that the product relaunch comes at a time of cultural shift, tapping into the younger generations’ craving for nostalgia.

“Gen Z are a lot about mental health, slowing things down, realising what we had in the past was great. While they’re highly connected digitally, Gen Z is driving a renewed appreciation for analog, choosing film not in place of digital, but alongside it,” says Georgievski.

Personal Journeys and Cultural Impact

Film photography is experiencing a wave of revival alongside compact digital cameras. Both trends suggest that the instant gratification of smartphone cameras may no longer satisfy young people seeking deeper connections with their memories.

Denis Hasagic, a 25-year-old Sydney Super8 regular, initially saved up to buy a digital camera but instead picked up his dad’s old Pentax MZ-50 and started shooting film. Despite only four out of 37 photos turning out, Hasagic was hooked.

“I saved up all this money for a digital camera and then got a film camera for much cheaper and spent the extra money on film and development,” says Hasagic, who later bought a Pentax P30.

Hasagic appreciates the mindfulness that film photography demands, forcing him to slow down and embrace the unexpected. “There’s also the surprise element. When you get the scans back and the photo you thought was going to be really good turns out bad, but the photo you took accidentally is really amazing,” he shares.

Professional photographer Julia Sarantis, 29, echoes this sentiment. “Even though it’s heartbreaking, there are so many rolls [of film] that just didn’t turn out … but it’s magic when it happens,” she says. Sarantis discovered her love for film photography during a university elective and was captivated by the development process in the darkroom.

“I’ve always had an interest in old technology. But I think in a larger, cultural way it’s a deviation from the immediacy of digital technology,” says Sarantis.

Sydney Super8’s Vlahadamis acknowledges the digital age’s influence but remains hopeful about the future of film. He wishes more young people wanted physical prints alongside digital scans but appreciates their enthusiasm for old-school technology.

“You get one shot. We are in such an era right now where everything is instant … You’re going back to the future in a way,” he concludes.