Male bottlenose dolphins that form close friendships age more slowly than their solitary counterparts, according to groundbreaking research conducted by scientists at the University of New South Wales (UNSW). The study highlights the profound impact of social connections on biological ageing, drawing parallels between dolphins and humans.

Dolphins, much like humans, exhibit signs of ageing such as reduced energy, changes in skin texture, slower movement, and deteriorating eyesight. However, the new research suggests that dolphins possess a potent anti-ageing mechanism: strong social bonds. The study, led by Dr. Livia Gerber, analyzed dolphin cell samples and found that male dolphins with robust social networks aged more slowly at the cellular level.

Social Bonds as an Anti-Ageing Mechanism

“Social connections are so important for health that they slow down ageing at the cellular level,” stated Dr. Gerber, who conducted the research while at UNSW and now works with CSIRO. “We knew social bonds helped animals live longer, but this is the first time we have shown that they affect the ageing process.”

Male dolphins are known for their enduring friendships, often maintaining relationships that span decades. This unique social structure was a key focus of Dr. Gerber’s study. “Female dolphins have a different pattern of social bonding influenced by having offspring of similar age,” she explained, noting that male dolphins, in contrast, form long-lasting and deep social bonds.

These friendships resemble human relationships, with dolphins engaging in activities such as playing, surfing waves, and resting side by side. “It reminds me of two kindergarten buddies who stay together through school, careers, and retirement, sharing all of life’s joys and challenges,” Dr. Gerber remarked.

The Stress of Solitude

In contrast, solitary dolphins face a more stressful existence, having to hunt alone, compete for mates without support, and confront predators without backup. “Having friends gives dolphins a support network that makes life’s challenges much more manageable,” Dr. Gerber emphasized.

The research team constructed a detailed picture of a dolphin population in Shark Bay, Western Australia, using years of observational data to analyze social connections. According to Dr. Gerber, dolphins with close social bonds are consistently observed together, underscoring the strength of their relationships.

Epigenetic Clocks: A New Measure of Ageing

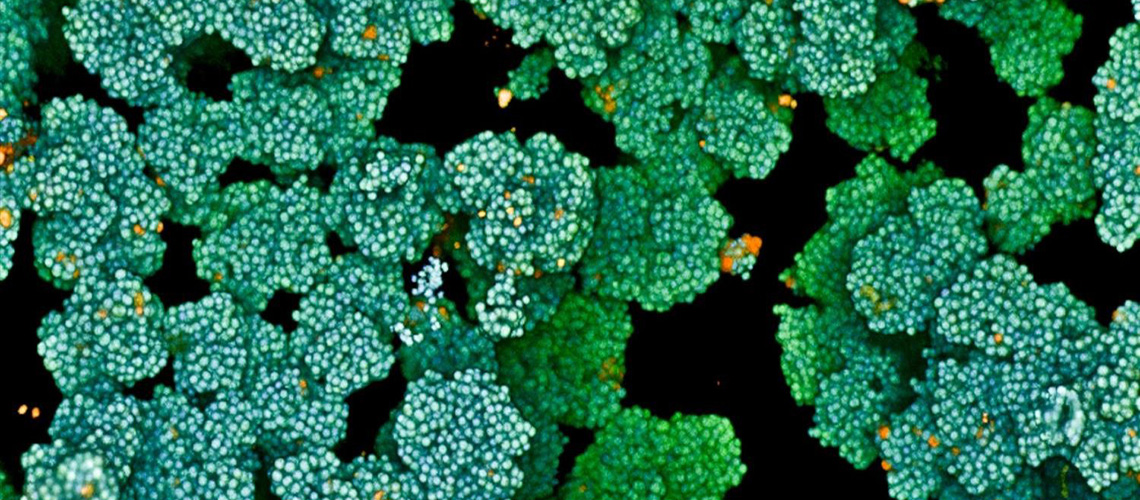

Most studies on the impact of social bonds on ageing have focused on chronological age and lifespan. However, this research employed DNA markers to develop an “epigenetic clock,” offering a more accurate measure of biological age and overall health.

In humans, epigenetic clocks have been used to assess how factors such as pollution, depression, and social bonds affect biological age. “Increasingly, we are also using epigenetic data to advance our knowledge of the ecology of wild populations, including the epigenetic clocks used here,” noted co-author Professor Lee Rollins from the UNSW School of Biological, Earth & Environmental Sciences.

The researchers examined 50 skin tissue samples from 38 bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay, finding that those with stronger social bonds aged more slowly, suggesting they led less stressful lives. “The health benefits of friendship are not unique to humans but are a fundamental biological principle across social mammals,” Dr. Gerber stated.

Implications for Animal Welfare and Human Health

This research challenges traditional views on animal welfare, emphasizing that social needs are biological needs. Dr. Gerber advocates for further studies on friendship and ageing in other social animals such as elephants, primates, and wolves. “I am predicting that we will find that friendship is a natural anti-aging secret across social animals,” she said.

The findings also have implications for human health, suggesting that investing time in meaningful relationships should be as much a priority as maintaining a healthy diet and exercise routine. The research has been published in the journal Nature Communications Biology.