Scientists have long observed that Black women with estrogen-receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer, particularly those residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods, face more aggressive forms of the disease and poorer survival rates. However, the precise factors connecting these outcomes to the environments in which these women live have remained elusive—until now.

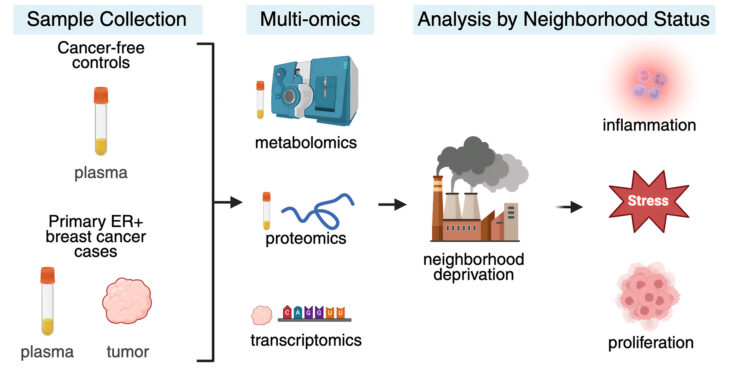

In a groundbreaking study, researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the University of Illinois Chicago have uncovered molecular signatures associated with neighborhood disadvantage. By analyzing plasma and tumor samples from women in the Chicago area with ER+ breast cancer, the team identified elevated levels of proteins, metabolites, and genes linked to inflammation and tumorigenesis in patients from disadvantaged neighborhoods compared to those from more affluent areas.

Exploring the Molecular Landscape

The research team, which included scientists from Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, conducted a comprehensive analysis of plasma from 91 pretreatment patients with ER+ breast cancer. This was compared with samples from 141 healthy control group participants who had no history or symptoms of breast cancer. The study focused on steroid hormone levels, global metabolite changes, and metabolites related to chronic stress and inflammatory proteins.

“The study sample included women who lived in very affluent neighborhoods as well as those from extremely disadvantaged areas,” said first author Hannah Heath, a predoctoral fellow in food science and human nutrition at Illinois. “We found that women who were living in disadvantaged neighborhoods—both those with cancer and the healthy controls—had extremely high levels of inflammatory proteins.”

Within the tumor samples, the researchers also noted dysregulated expression of genes related to DNA repair, both of which are associated with worsened prognoses. Participants were patients from three Chicago-area hospitals, and their addresses at the time of enrollment were used alongside data from the Area Deprivation Index to classify them into groups based on neighborhood disadvantage.

Neighborhood Disadvantage and Tumor Aggression

The study further analyzed 71 tumor samples from cancer patients, classifying the tumors by grade, with higher grades indicating more aggressive disease. Even among tumors of the same grade, those from women in disadvantaged neighborhoods showed increased inflammation compared to those from affluent areas.

“This is important because tumor grade is often what is used to determine how aggressive patients’ cancers are and what type of treatment they should receive,” Heath explained. “But based on these results, that protocol might not be benefitting people who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods because they still have much higher levels of inflammation.”

Interestingly, cancer patients from the most affluent neighborhoods exhibited increased levels of cortisol metabolites, while those from the most deprived areas had decreased levels, alongside significantly elevated levels of testosterone and cholesterol.

“We know that, generally, cortisol hormones are necessary to reduce inflammation. But when those hormones become dysregulated, they have the opposite effect and can increase inflammation. And that appears to be what’s happening with those living in disadvantaged areas,” Heath noted.

Implications for Future Research and Treatment

According to co-author Zeynep Madak-Erdogan, a nutrition professor and associate director for education at the Cancer Center at Illinois, the study’s findings establish a biological pathway linking social determinants of health to tumor aggression. This research not only documents disparities in breast cancer outcomes but also identifies specific, potentially modifiable molecular mechanisms—such as chronic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation—that may drive these inequities and represent actionable targets for intervention.

“Our analyses show that neighborhood disadvantage correlates with upregulation of inflammatory and proliferation-related gene expression within tumors themselves,” said Madak-Erdogan.

The study, published in the Journal of Proteome Research, was co-written by a team of experts from various institutions, including the University of Illinois College of Medicine, the University of Illinois Cancer Center in Chicago, and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. The research was supported by several organizations, including the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

As the scientific community continues to unravel the complex interplay between environment and health, this study highlights the critical need for targeted interventions that address the root causes of health disparities. By understanding the molecular underpinnings of these disparities, researchers hope to develop more effective treatments and improve outcomes for all patients, regardless of their socioeconomic status.