Christianity, Rob Norman tells worshippers at a church in Adelaide’s inner southern outskirts, is a “sleeping giant” in politics. It is a Sunday morning in May 2021. The charismatic pastor with a buzz cut is one of several leaders at Pentecostal and evangelical churches in the area who have begun encouraging followers to get active in politics, prompted by the South Australian parliament’s plans to decriminalize abortion.

“Some people say it’s a dirty business, but we’ve got to be there,” Norman, who would later join the Australian Christian Lobby as its Queensland director, says. At the end of his 30-minute sermon, Norman name-drops Alex Antic, a first-time Liberal senator with a minimal profile in Canberra, who watches on from the crowd. “Drop Alex an email. It’s easy to find him. He’ll start sending his newsletter to you. You’ll start to get enlightened,” he says.

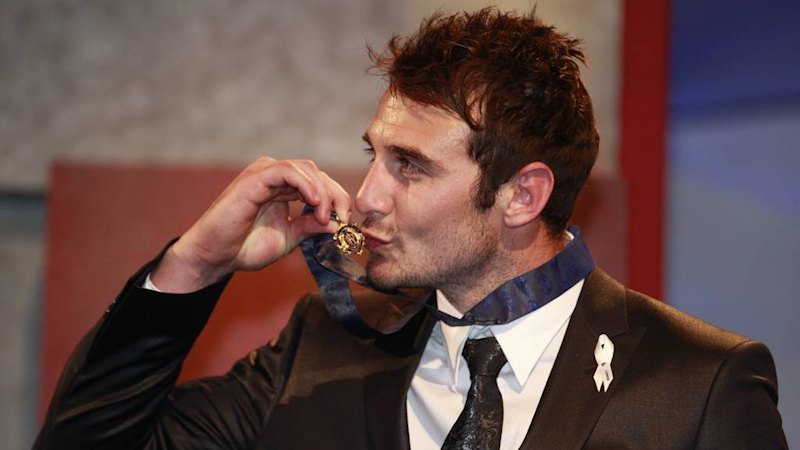

In the four years since, Antic, a former lawyer turned city councillor, has risen from an influential up-and-comer in the state to South Australia’s top factional warlord. Through his efforts recruiting Christian activists and anti-government skeptics into the state’s Liberal regional and metropolitan branches, the once fringe conservative senator now wields considerable influence over the state division’s policy and preselection processes.

Antic’s Ascendancy in South Australian Politics

Antic’s world, however, is not one of broad church Liberalism. His vision leaves little room for moderates and centrists, contrasting sharply with the inclusive creed of former Prime Minister John Howard. “It’s not even factional warfare … it’s a takeover,” says one senior South Australian Liberal.

The federal Liberal party, facing an existential crisis, now views South Australia as a roadmap—or a cautionary tale—for its other divisions. When Antic watched Norman’s impassioned “call to the political realm” in 2021, his supporter base of Pentecostal and evangelical churchgoers around the state had already tallied around 500.

Antic’s pitch to local churches was that the party needed more conservatives in its membership following changes in South Australia to decriminalize abortion. His opposition to “woke” views on gender and sexuality also appealed to social conservatives. In a podcast with former Hillsong preacher Pat Mesiti in January 2022, Antic lamented the lack of “God-fearing, conservative people” in politics.

Building “Alex’s Army”

Antic’s strategy was clear: recruit disenfranchised individuals frustrated with COVID-19 vaccine mandates and lockdowns, who had drifted towards more conservative and far-right minor parties. With key allies, including backbencher Tony Pasin, Antic’s strategy to reshape the party from the grassroots was in full force.

Longstanding Liberal officeholders in state and federal branches were among the first to witness the shift in dynamics. With hundreds of new members, Antic’s supporters quickly outnumbered the established members in several annual general meetings.

“We signed up to help Alex Antic,” new members would often say, reflecting the senator’s growing influence.

A Party Vulnerable to Manipulation

South Australia’s moderate faction had been in the Liberal party’s driver’s seat for decades. However, the departure of Christopher Pyne in 2019 left a leadership vacuum. Antic recognized this and filled a “market niche,” according to a state Liberal speaking anonymously.

“[Liberal state] council is extremely easy to manipulate. I’m a moderate. My side did it for years and years and years,” another says. But the party’s vulnerability allowed Antic to capitalize on the situation, recruiting what some describe as “angry activist Christians.”

Antic’s membership drive in state and federal electorate conventions provided him with allies on various councils, giving him a respectable voting bloc. This influence allowed him to determine important state executive roles and endorse Liberal candidates for elections.

Impact and Controversy

Antic’s strategy has already borne fruit. Ahead of the 2025 election, he secured the top spot on the party’s federal Senate ticket, displacing Liberal frontbencher Anne Ruston and stirring controversy over the party’s “women problem.”

Policy consequences of this shift are evident. Last year, Antic allies in the state parliament introduced a bill requiring South Australians seeking an abortion from 28 weeks to give birth, which was narrowly defeated in a conscience vote. At a state council meeting in late May, the council voted to urge the federal Liberal party to repeal its net zero by 2050 policy—a position not adopted by the state parliamentary party.

Future Prospects and Challenges

Antic’s management of his allies revolves around a simple newsletter, “Truth to Power.” It provides followers with insights into his priorities and directions for upcoming factional battles. In a May newsletter following the federal election, Antic urged supporters not to be “despondent” about the results and not to abandon the Liberals for right-wing minor parties.

Antic’s rise has coincided with several state MPs exiting the party, while moderates and traditional conservatives have opted not to renew their memberships. Some describe the state party as a “hard right, religious political vehicle” that is Liberal only in name.

Despite his influence, Antic has struggled to convert state success into federal victories. All Antic-backed lower house candidates failed in the May federal election, while a moderate candidate, Tom Venning in Grey, was the Liberal party’s only success story in South Australia.

Efforts to reclaim the party are underway. In a recent AGM in Sturt—a moderate stronghold—more than 300 local members attended, and the moderate faction successfully gained officeholder positions.

“We really have to get back to being a Liberal party, not a pseudo Family First party or an anti-vaccines party. You know, that’s not us,” one Liberal member stated.

The consequences of failing to reclaim the party could be devastating. “There comes a point where it becomes harder and harder to come back. And I think that’s what’s happening in South Australia,” a former state MP warns.