In a groundbreaking study conducted in Sweden, researchers have explored the relationship between neighborhood-level social capital and the incidence of major psychiatric disorders. The study, which tracked a cohort of over 1.4 million people in Stockholm County for up to 15 years, sheds light on how social cohesion can influence mental health outcomes, particularly non-affective psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder without psychosis.

The research, published recently, highlights the protective role that neighborhood social capital, specifically personal trust, can play in reducing the incidence of severe mental illnesses. However, the study also reveals that these protective effects are not uniformly experienced across different demographic groups, emphasizing the complex interplay between social environments and mental health.

Understanding Social Capital and Mental Health

Social capital refers to the shared resources, values, and connections within a community that enable individuals to achieve common goals. It is often seen as a multidimensional construct that can belong to individuals, groups, or both. In the context of mental health, social capital is theorized to protect against mental health issues by fostering strong social ties and acting as a buffer during times of adversity.

Previous research has suggested that social capital might be linked to lower risks of non-affective psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, which tend to show strong social gradients based on socioeconomic status, neighborhood deprivation, and social fragmentation. However, the evidence has been largely cross-sectional, and the specific role of social capital in mental health has remained unclear.

Key Findings from the Swedish Study

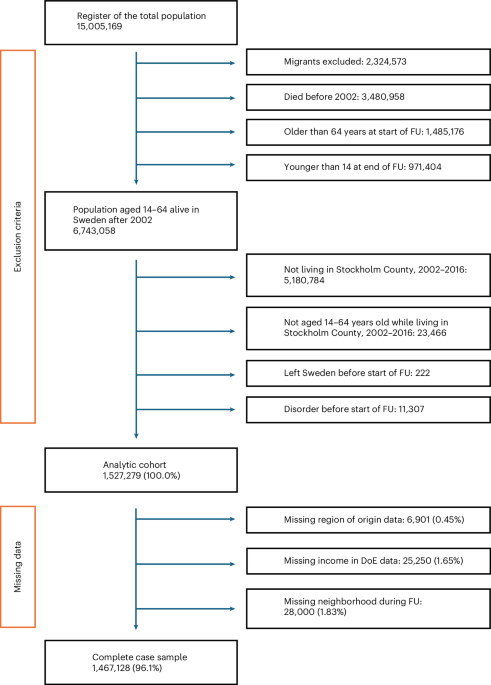

The Swedish study utilized data from Psychiatry Sweden, a linked database of Swedish population registers, and neighborhood social capital data derived from the Stockholm Public Health Cohort (SPHC) survey conducted in 2002. The study aimed to investigate whether time-varying exposures to different domains of social capital were associated with the incidence of psychiatric disorders.

“The study finds protective effects of greater exposure to neighborhood-level personal trust on subsequent lower rates of severe mental illness, including non-affective psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder without psychosis,” the researchers noted.

Importantly, the study found that the protective effects of social capital, particularly personal trust, were more pronounced for the majority Swedish-born population and those of European or mixed heritage. In contrast, individuals of African and Middle Eastern heritage experienced increased rates of these outcomes in neighborhoods with higher levels of personal trust, suggesting that social capital can have both protective and harmful effects depending on perceived group membership.

Implications for Public Policy

The findings of this study have significant implications for public policy, particularly in terms of addressing mental health disparities and promoting social cohesion. The researchers suggest that promoting bonding or relational social capital for the majority population may not be protective for all groups and could exacerbate risks for some, thereby widening inequalities.

To address these challenges, the study advocates for strategies that promote positive intergroup contact and the development of inclusive social capital that bridges different sociodemographic groups. This could involve community-based interventions that foster cooperation and connectivity between migrant and non-migrant communities, enhancing opportunities for employment and collective action.

“Facilitating bridging ties between migrant and Swedish groups could be prioritized in line with a group inclusion model,” the study suggests.

Expert Opinions and Future Research

Experts in the field of social psychology and public health have weighed in on the study’s findings, emphasizing the need for further research to understand the mechanisms through which social capital influences mental health. They highlight the importance of considering the role of intergroup contact theory and the potential for social capital to either mitigate or exacerbate stress and mental health outcomes.

Future research should explore the impact of bridging social capital, which promotes positive intergroup contact, and examine whether unbiased, group-specific measures of social capital exert protective effects for different demographic groups. Additionally, there is a need to investigate the potential causal mechanisms at play, including the role of stress reactivity and neurobiological factors in the development of psychiatric disorders.

Conclusion

The Swedish study provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between social capital and mental health, highlighting both the protective and potentially harmful effects of social cohesion. As policymakers and researchers continue to explore ways to improve mental health outcomes, the findings underscore the importance of fostering inclusive communities that support diverse populations and promote positive intergroup interactions.

As the world grapples with rising mental health challenges, understanding the role of social environments and community support systems will be crucial in developing effective interventions and policies that benefit all members of society.