In a groundbreaking revelation, scientists have uncovered the reproductive secrets of the giardia parasite, a notorious organism responsible for infecting millions worldwide. This discovery, led by Australian researchers, not only solves a decades-old mystery but also offers new insights into how infections can jump from animals to humans, potentially giving rise to zoonotic diseases.

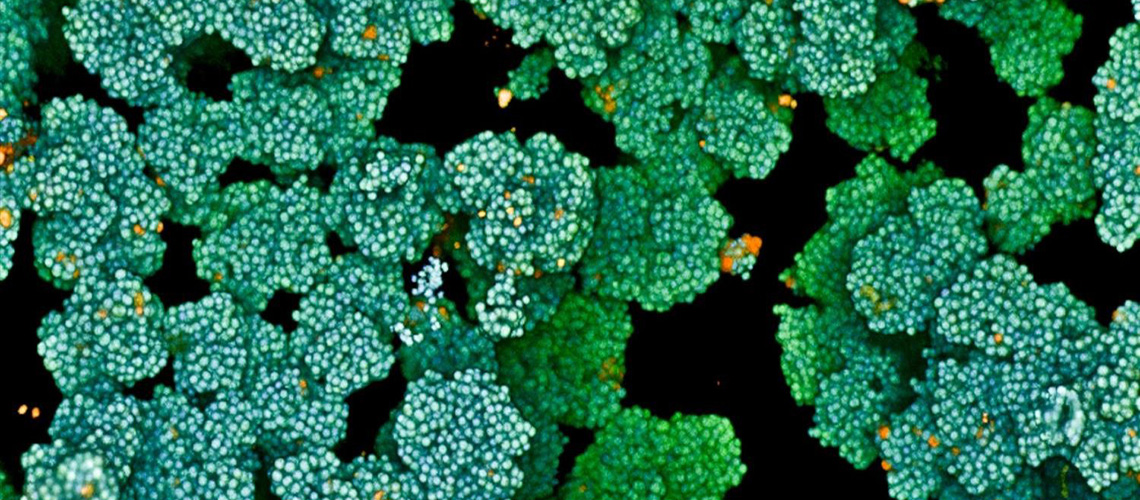

Giardia, often referred to as “beaver fever,” has been a public health concern for years. The parasite infects approximately 280 million people annually, including 600,000 Australians, by colonizing the small intestine and causing symptoms such as cramping, bloating, and diarrhea. The infection spreads through hardy cysts that can survive in water for months, even resisting chlorine treatment. These cysts are ingested through contaminated water or food, allowing the parasite to jump between hosts, including pets and their owners.

Giardia’s Reproductive Enigma

For decades, a significant question has lingered over giardia: does it reproduce sexually or asexually? Understanding this is crucial as it impacts the parasite’s evolution and spread, particularly given its growing resistance to frontline drugs, with 20% of cases now untreatable by major medicines. The mystery has not only been a public health concern but also a challenge to evolutionary biology.

Professor Aaron Jex, head of the parasite lab at Melbourne’s WEHI research center, alongside international colleagues, has finally put this evolutionary enigma to rest. By employing advanced genetic screening techniques on 100 different isolates from humans and various animals, they discovered both sexual and asexual types of giardia.

The Red Queen Hypothesis and Asexual Scandals

This discovery ties into the Red Queen hypothesis, inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, which suggests that species must constantly evolve to survive. While simple organisms like bacteria reproduce quickly through cloning, more complex organisms rely on sexual reproduction to shuffle genes, shedding bad mutations and accelerating natural selection.

Giardia has long been considered one of the last true “asexual scandals,” as it appeared to persist without sex, defying the typical evolutionary strategy. However, Jex’s research revealed that the sexual form of giardia was present only in humans, while the asexual version infected a broader range of hosts.

“This was another piece of evidence into how zoonoses may arise,” said Professor Aaron Jex.

A New Theory for Zoonotic Diseases

The findings suggest a new theory for how pathogens can jump from animals to humans. Sexual parasites tend to adapt quickly to a single host, discarding bad mutations. In contrast, asexual organisms accumulate these mutations, potentially allowing them to infect a wider range of hosts as they lose specificity.

This theory posits that as asexual giardia loses evolutionary fitness, it gains the ability to infect diverse hosts, a process that may have implications for understanding zoonotic disease emergence, similar to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Asexual lineages basically became like a tool species could use that would allow them to relax evolutionary selection and infect new hosts,” noted Jex.

Implications for Public Health

The study’s findings are significant for public health, offering insights that could inform the development of more effective treatments for giardia. While the asexual, species-jumping type of giardia causes about half of human infections, it is ultimately doomed due to accumulated mutations, a phenomenon known as “mutation meltdown.”

This research underscores the essential nature of sexual reproduction in maintaining genetic health and adaptability, echoing the Red Queen’s warning about the relentless race for survival.

The discovery not only advances our understanding of giardia but also highlights the broader implications for zoonotic diseases, one of humanity’s greatest threats. As scientists continue to explore these dynamics, the findings may pave the way for new strategies in combating infectious diseases.