For centuries, nature has quietly outperformed human engineering. Octopuses and cuttlefish can vanish against coral, ripple their skin into spines, or flash patterns to communicate—sometimes all at once. Now, a team of researchers from Penn State and the Georgia Institute of Technology claims it has taken a major step toward replicating that biological magic in a synthetic material that behaves more like living skin than plastic.

In a new peer-reviewed study published in Nature Communications, engineers report a novel way to “print” multifunctional smart materials that can hide and reveal images, change texture, bend into complex shapes, and even embed information that can only be read under specific conditions. This innovative material, described as a cephalopod-inspired “smart synthetic skin,” is made from hydrogel and fabricated using a technique the team calls halftone-encoded 4D printing.

Revolutionizing Material Science

Most synthetic materials—even advanced ones—are designed to do just one thing well. A coating might change color, a polymer might bend when heated, or a gel might respond to moisture. However, combining multiple dynamic behaviors in a single, soft material has remained a major challenge. Researchers argue their approach overcomes that constraint by digitally embedding instructions directly into the material itself.

“Cephalopods use a complex system of muscles and nerves to exhibit dynamic control over the appearance and texture of their skin,” co-author and professor at Penn State, Dr. Hongtao Sun, said in a press release. “Inspired by these soft organisms, we developed a 4D-printing system to capture that idea in a synthetic, soft material.”

The Science Behind 4D Printing

The term “4D printing” refers to structures that change after printing. Unlike conventional 3D printing, where a shape is fixed once fabrication ends, 4D-printed materials are engineered to transform in response to external stimuli, such as heat, solvents, or mechanical stress. In this case, the researchers used a hydrogel—a water-rich, jelly-like material already known for its responsiveness—to create a film that can reconfigure itself in multiple ways.

The novel system is unusual in how it programs the material’s behavior. Instead of stacking various components or embedding electronics, researchers used a printing strategy borrowed from graphic design: half-toning. In newspapers and photographs, halftone dots create the illusion of continuous tones using only black and white ink. Here, the researchers used a similar logic to encode “binary” regions into the hydrogel.

“In simple terms, we’re printing instructions into the material,” Dr. Sun explained. “Those instructions tell the skin how to react when something changes around it.”

Applications and Demonstrations

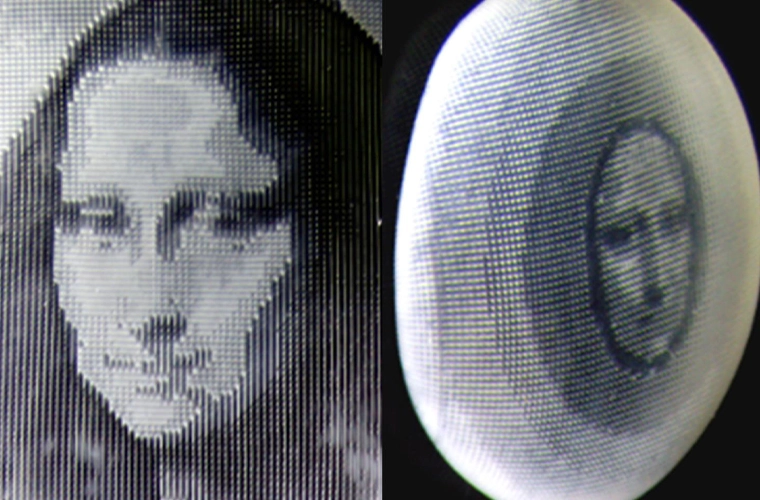

One of the most striking demonstrations described in the study involves hiding and displaying images. To showcase the effect, the team encoded a halftone version of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa into a thin hydrogel film. When washed with ethanol, the film became transparent, and the image disappeared entirely. When placed in ice water or gradually heated, the portrait re-emerged with high contrast as the gel swelled or contracted.

According to Haoqing Yang, a doctoral candidate in industrial and manufacturing engineering at Penn State and the paper’s first author, the choice of image was symbolic rather than technical. “This behavior could be used for camouflage, where a surface blends into its environment, or for information encryption, where messages are hidden and only revealed under specific conditions,” Yang said.

Crucially, the image does not simply fade in and out. It is revealed because different regions of the hydrogel scatter or transmit light depending on temperature and solvent exposure. The visual effect is reversible and repeatable, allowing the same material to cycle between hidden and visible states.

Beyond Optics: Mechanical Encoding

The study also demonstrates a second, less obvious layer of information encoding. Even when an image is optically invisible, it can still be recovered mechanically. By gently stretching the smart skin and measuring its deformation using digital image correlation, the researchers showed that invisible patterns can be reconstructed from strain maps. In other words, the information is still there—it just requires a different “key” to read it.

Beyond optics and encryption, the smart skin also exhibits controlled shape-morphing behavior. A flat sheet can curl into dome-like structures, saddles, or textured surfaces reminiscent of cephalopod skin. Unlike many other shape-changing materials, this transformation does not rely on multiple layers or composites. Instead, the geometry appears from how the halftone patterns are arranged within a single sheet.

“Similar to how cephalopods coordinate body shape and skin patterning, the synthetic smart skin can simultaneously control what it looks like and how it deforms, all within a single, soft material,” Dr. Sun said.

Future Implications and Applications

The ability to combine these behaviors—optical change, mechanical response, surface texture, and shape transformation—within one material system is what sets this breakthrough apart from other synthetic materials. Previous approaches often required stacking materials or sacrificing one function to achieve another. Here, the binary halftone strategy allows the functions to be co-designed digitally before printing.

Researchers emphasize that this work builds on earlier studies of smart hydrogels but significantly expands their capabilities. In prior efforts, the team concentrated on programming mechanical properties and shape changes. In the new study, they demonstrate that halftone-encoded printing enables multiple functions to be integrated and coordinated within a single film.

Going forward, Dr. Sun and his colleagues say the next step is scalability. They envision a general manufacturing platform that permits precise digital encoding of diverse functions into dynamic materials. While the technology is still at a laboratory stage, the implications could be significant. By borrowing ideas from octopus skin and combining them with digital manufacturing, the researchers have shown that materials can be programmed to behave more like systems than static objects.

This shift opens the door to a wide range of tangible applications. In everyday contexts, materials like this could lead to clothing or architectural surfaces that automatically adjust insulation, texture, or appearance in response to temperature and weather, or to packaging that reveals hidden information only under specific conditions. In more advanced settings, the same principles could enable soft robots that move and adapt without motors or electronics, medical implants that change stiffness or shape inside the body, or physical objects that store encrypted data not in chips but in how the material itself deforms or transmits light.

“This interdisciplinary research at the intersection of advanced manufacturing,” Dr. Sun explains. “Intelligent materials and mechanics opens new opportunities with broad implications for stimulus-responsive systems, biomimetic engineering, advanced encryption technologies, biomedical devices, and more.”

By embedding multiple functions directly into matter rather than layering components on top of one another, the approach hints at a future in which responsiveness, computation, and security are built into materials from the moment they are manufactured. If these capabilities can be scaled and adapted beyond hydrogels, future “smart skins” may blur the line between material and machine—much like their biological inspirations have done all along.