Last year, astronomers were captivated by a runaway asteroid zipping through our solar system from a distant realm, traveling at an astounding speed of 68 kilometers per second—over twice the speed of Earth’s orbit around the sun. Now, imagine an even more formidable cosmic traveler: a black hole moving at a staggering 3,000 kilometers per second. Such an entity could remain undetected until its immense gravitational forces began to disrupt the orbits of the outer planets.

This scenario, while seemingly far-fetched, is gaining credibility. In the past year, mounting evidence suggests that runaway supermassive black holes, capable of tearing through galaxies, are not just theoretical. Astronomers have identified clear signs of these cosmic phenomena, and there is growing evidence that smaller, undetectable runaways may also exist.

Theoretical Foundations of Runaway Black Holes

The concept of runaway black holes has its roots in the 1960s when New Zealand mathematician Roy Kerr found a solution to Einstein’s general relativity equations, describing spinning black holes. This led to two pivotal discoveries about black holes.

Firstly, the “no-hair theorem” posits that black holes are characterized solely by their mass, spin, and electric charge. Secondly, according to Einstein’s famous equation E = mc², energy possesses mass. Kerr’s solution indicates that up to 29% of a black hole’s mass can be rotational energy.

English physicist Roger Penrose theorized 50 years ago that this rotational energy could be released. A spinning black hole acts like a colossal battery, capable of discharging vast amounts of spin energy. In fact, a black hole can harbor about 100 times more extractable energy than a star of the same mass. When two black holes merge, much of this energy can be unleashed in mere seconds.

“If the spins of the two colliding black holes are aligned the right way, the final black hole can be rocket-powered to speeds of thousands of kilometers per second.”

From Theory to Observation: Detecting Runaway Black Holes

The theoretical framework laid the groundwork for real-world observations. The LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave observatories began detecting gravitational waves from colliding black holes in 2015. Among the most thrilling discoveries were black hole “ringdowns,” akin to a tuning fork’s resonance, revealing insights into their spin. The faster they spin, the longer they resonate.

Enhanced observations of coalescing black holes disclosed that some pairs had randomly oriented spin axes and substantial spin energy. This reinforced the plausibility of runaway black holes. Traveling at 1% of light speed, their trajectories would be nearly linear, unlike the curved orbits of stars in galaxies.

Runaway Black Holes in the Cosmos

The final piece of the puzzle emerged with the actual discovery of runaway black holes. While detecting smaller runaway black holes remains challenging, those of a million or billion solar masses create significant disturbances in their wake, affecting stars and gas as they traverse a galaxy.

These black holes are predicted to leave contrails of stars, formed from interstellar gas, similar to the cloud contrails left by jet planes. Stars form from collapsing gas and dust attracted to the passing black hole, a process that could span tens of millions of years as the runaway black hole crosses a galaxy.

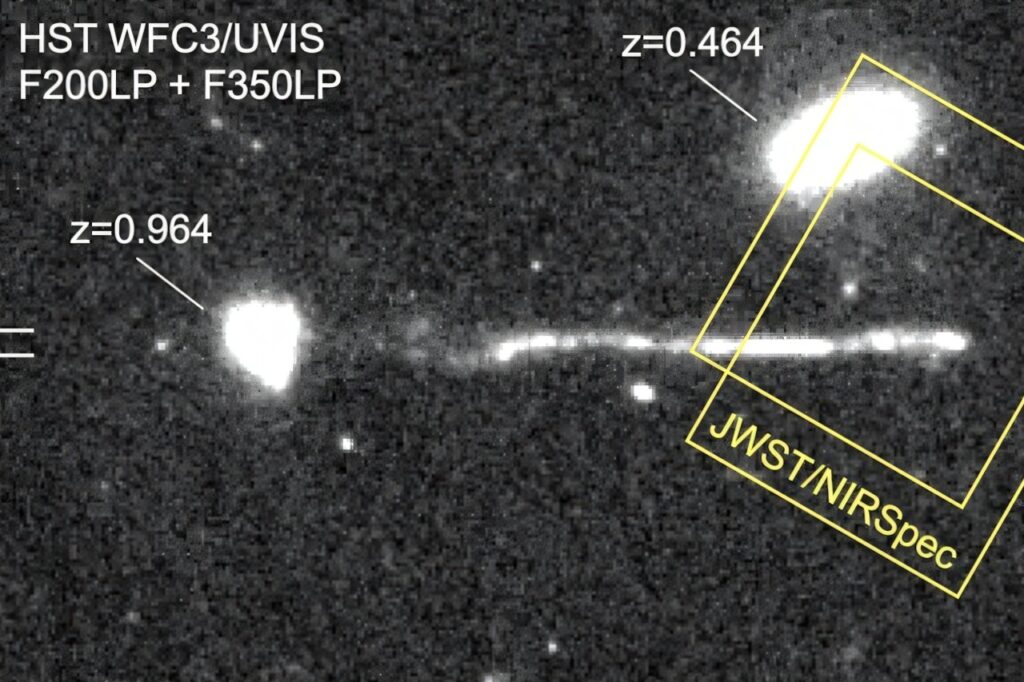

“In 2025, several papers showed images of surprisingly straight streaks of stars within galaxies. These seem to be convincing evidence for runaway black holes.”

Implications and Future Prospects

One notable study, led by Yale astronomer Pieter van Dokkum, described a distant galaxy imaged by the James Webb telescope, featuring a bright contrail 200,000 light years long. The contrail suggested a black hole with a mass 10 million times that of the sun, traveling at nearly 1,000 kilometers per second.

Another study highlighted a long, straight contrail across a galaxy called NGC3627, likely caused by a black hole about 2 million times the mass of the sun, moving at 300 kilometers per second. Its contrail extended approximately 25,000 light years.

If these massive runaway black holes exist, smaller counterparts should also be present. Gravitational wave observations suggest that some black holes merge with the opposing spins necessary to create powerful kicks, enabling them to travel between galaxies.

Runaway black holes, traversing and between galaxies, are a new facet of our universe’s complexity. While the odds of one entering our solar system are minuscule, the discovery enriches our understanding of the cosmos, adding a layer of excitement and intrigue to the story of our universe.