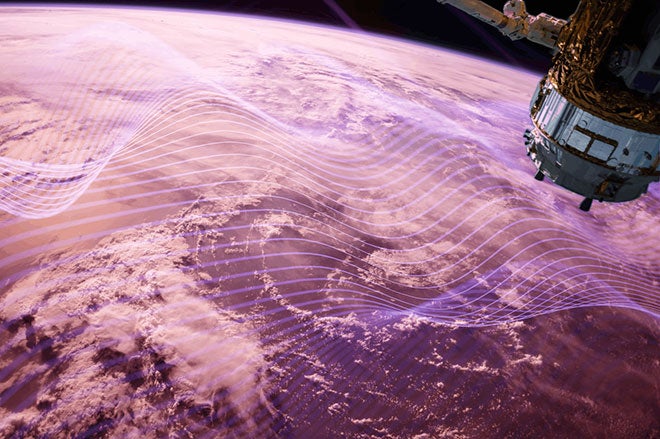

Far above the Earth, in the thin atmosphere that bridges our planet and outer space, an invisible but significant process is unfolding. The increasing concentration of carbon dioxide is manifesting its impact far beyond the familiar consequences of heatwaves, melting ice caps, and rising sea levels. It is quietly altering the ionosphere, a region critical for global communication, according to a recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters.

The study, conducted by researchers from Kyushu University and Japan’s National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, reveals how rising CO₂ levels are affecting the ionosphere—a layer filled with charged particles that is essential for long-distance radio communication. This research introduces a new dimension of climate change that is often overlooked.

The Hidden Mirror in the Sky

The E region of the ionosphere, located about 60 miles above the Earth’s surface, is a thin layer of metallic ions composed of elements like iron, magnesium, and calcium. Under certain conditions, these ions form a sporadic-E layer (Es), which acts as a natural mirror reflecting radio waves back to Earth. This phenomenon is crucial for pilots, ship crews, and emergency workers who rely on radio communication over long distances.

However, the sporadic-E layer can also disrupt signals from navigation systems, leading to poor-quality reception. Professor Huixin Liu from Kyushu University explains, “Es are sporadic, as the name indicates, and are unpredictable. But when they occur, they can disrupt HF and VHF radio communications.” Her recent simulations suggest that as global temperatures rise, these disruptions may become more frequent.

Simulating the Atmosphere of the Future

Using the GAIA whole-atmosphere model, Liu’s team simulated the effects of doubling carbon dioxide levels from pre-industrial levels of 315 parts per million to 667 ppm—a concentration scientists expect by 2100. For context, the global average in 2024 was approximately 423 ppm. The simulations focused on the summer months when the Es layers are most dynamic, examining the vertical ion convergence (VIC) that influences the thickness and duration of these layers.

The results showed that with doubled CO₂ levels, VIC increases globally at altitudes between 100 and 120 kilometers. Metallic “hotspots” where ions cluster shift downward by about five kilometers, forming closer to the atmospheric surface. These layers also become thicker and last longer, particularly overnight.

Why More Carbon Means a Cooler Sky

While it may seem counterintuitive, increased CO₂ cools the upper atmosphere while warming the surface. Closer to Earth, carbon dioxide traps heat, but at higher altitudes, it radiates heat into space, cooling the thin air above 60 miles. As the thermosphere cools, its density decreases, leading to fewer collisions between ions and neutral particles. “With fewer collisions, metallic ions move more freely,” Liu explains. “That enables them to build up into stronger and denser layers.”

These changes also alter the pattern of daily high-altitude winds that move east and west, sweeping metallic ions into bands. With more CO₂, these winds change, driving ions into new zones of convergence, enhancing the Es layer.

Testing Patterns from the Model Around the World

To validate their findings, the team modeled simulations for Kokubunji, Japan, and Arecibo, Puerto Rico, which are at different geomagnetic longitudes. Both locations showed the same general trend. In Japan, Es activity that typically peaked during the day began to persist into the night under high CO₂ levels. In Puerto Rico, the layers became denser and appeared at lower altitudes.

Globally, if emissions continue on their current trajectory, the Es phenomenon will likely strengthen in other parts of the world as well.

The Ripple Effect of Climate Change

While these changes in the ionosphere may go unnoticed by the general public, they are significant for pilots, radio operators, and space agencies. Sporadic-E layers can distort radio waves, interfering with high-frequency signals used in aviation, military radar, and maritime communication.

“This cooling does not necessarily mean all is good,” Liu cautions. “It shrinks the air density in the ionosphere and strengthens the wind circulation. This can also change the orbit and lifetime of satellites and space debris and disrupt radio communications from localized small-scale plasma irregularities.”

For everyday individuals, this is a reminder that climate change’s impact extends beyond the Earth’s surface, affecting even the uppermost layers of the atmosphere.

A Delicate Balance in the Ionosphere

The physics of the Es layer is complex yet fascinating. Metallic ions move along Earth’s magnetic field lines in an invisible dance of electric and wind forces. As the air thins, collisions between ions and neutral particles decrease, allowing ions to respond more strongly to magnetic and wind forces.

In the GAIA simulations, this led to a distinct transition from slow to fast movement, intensifying the vertical convergence of ions that generates the sporadic E layer. It’s akin to cream swirling into coffee, where changing viscosity creates unexpected patterns.

What Lies Ahead

Researchers plan to refine their model by integrating GAIA simulations with real satellite and radar data. Future work will address local chemistries and gravity waves and their influence on metallic layers in the ionosphere. The goal is to improve forecasting capabilities for sporadic E events, which could have serious implications for aviation and telecommunications industries.

For Liu, the work has broader implications. “Global warming not only affects the ground but goes well into space,” she notes, highlighting that the climate narrative extends beyond where the air thins out, reaching into the fragile boundary where our technology meets the atmosphere.

Practical Implications of the Research

Understanding how carbon dioxide affects the ionosphere could help protect communication systems dependent on radio waves. Future air traffic control communications, maritime networks, and emergency broadcast systems may need redesigning due to a stronger and lower sporadic E layer.

The study also suggests changes in satellite orbits and the lifetime of space debris with the cooling of the thermosphere. As global reliance on satellite and radio infrastructure grows, these findings could help engineers design more resilient systems to ensure that as the atmosphere changes, the connections underpinning modern life remain robust.

Research findings are available online in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.