A groundbreaking noninvasive method for measuring blood glucose levels, developed by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), promises to spare diabetes patients the discomfort of frequent finger pricks. The innovative approach utilizes Raman spectroscopy, a technique that analyzes the chemical composition of tissues by shining near-infrared or visible light on them, to create a device that can measure blood glucose levels without the need for needles.

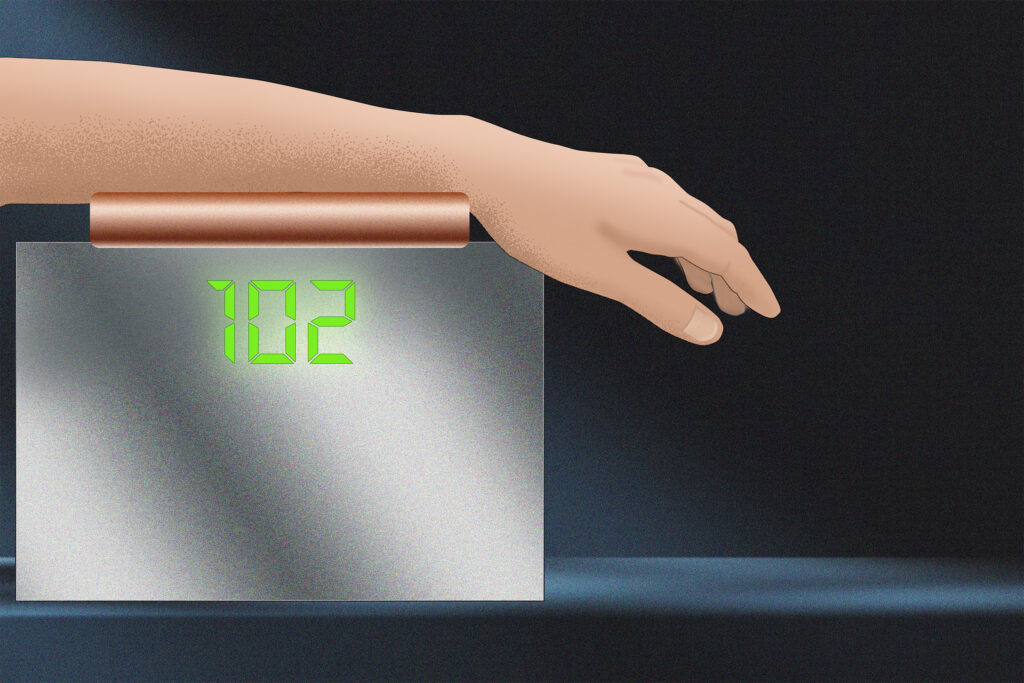

The MIT team has successfully tested a shoebox-sized prototype of this device, which demonstrated accuracy comparable to commercial continuous glucose monitoring sensors that require a wire to be implanted under the skin. Although the initial device is too large to be worn as a sensor, a wearable version has been developed and is currently undergoing testing in a small clinical study.

Breakthrough in Noninvasive Glucose Monitoring

Traditionally, diabetes patients have had to measure their blood glucose levels by drawing blood and testing it with a glucometer. Some have turned to wearable monitors that provide continuous glucose measurements via sensors inserted just under the skin. However, these sensors can cause skin irritation and require regular replacement.

In pursuit of a more comfortable alternative, researchers at MIT’s Laser Biomedical Research Center (LBRC) have been exploring noninvasive sensors based on Raman spectroscopy. This technique reveals the chemical composition of tissues by analyzing how near-infrared light is scattered as it encounters different molecules.

In 2010, LBRC researchers demonstrated that they could indirectly estimate glucose levels by comparing Raman signals from the interstitial fluid with reference blood glucose measurements. Although reliable, this method was not practical for developing a glucose monitor. A recent breakthrough allowed the team to directly measure glucose Raman signals from the skin, overcoming the challenge of isolating the glucose signal from other molecular signals.

Innovative Device Design and Testing

To achieve this, the researchers shone near-infrared light onto the skin at a different angle from which they collected the Raman signal, enabling them to filter out unwanted signals. The initial measurements were taken using equipment the size of a desktop printer, but the team has since reduced the device’s size by focusing on just three spectral bands in the Raman spectrum. This approach significantly reduces the equipment’s complexity and cost.

“By refraining from acquiring the whole spectrum, which has a lot of redundant information, we go down to three bands selected from about 1,000,” said Arianna Bresci, MIT postdoc and lead author of the study. “With this new approach, we can change the components commonly used in Raman-based devices, and save space, time, and cost.”

In a clinical study at the MIT Center for Clinical Translation Research, the device was used to take readings from a healthy volunteer over a four-hour period. The subject consumed glucose drinks to induce changes in blood glucose concentration, and the device’s accuracy was found to be on par with two commercially available invasive glucose monitors.

Future Developments and Implications

Following this successful study, the researchers have developed a smaller prototype, about the size of a cellphone, which is currently being tested as a wearable monitor in healthy and prediabetic volunteers. Plans are underway for a larger study involving diabetic patients at a local hospital next year.

The team is also working on further miniaturizing the device to the size of a watch and ensuring it can accurately read glucose levels from individuals with different skin tones. These advancements could revolutionize diabetes management, offering a painless, convenient alternative to traditional glucose monitoring methods.

The research, funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Korean Technology and Information Promotion Agency for SMEs, and Apollon Inc., represents a significant step forward in the quest for noninvasive medical technologies. As the global prevalence of diabetes continues to rise, innovations like this could improve the quality of life for millions of patients worldwide.

“If we can make a noninvasive glucose monitor with high accuracy, then almost everyone with diabetes will benefit from this new technology,” said Jeon Woong Kang, MIT research scientist and senior author of the study.