In a famous remark, Albert Einstein once asked whether the Moon continues to exist when nobody is looking. This startling comment stemmed from Einstein’s deep distrust of a branch of physics called quantum mechanics, the mind-bending theory that brilliantly describes the atomic microworld. Celebrating its centenary, quantum mechanics has become the most successful scientific theory of all time, accurately explaining the behavior of matter from subatomic particles to stars. It has given us technological marvels such as lasers, transistors, MRI machines, superconductors, and artificial intelligence.

Despite underpinning much of modern technology, the foundations of quantum mechanics defy everyday notions of reality and intuition. A century on, scientists remain divided over its interpretation. These interpretational woes have been highlighted by the emergence of a second quantum revolution: “Quantum 2.0” or quantum information science, promising even greater technological and economic advancements. In May 2023, Minister Ed Husic announced Australia’s National Quantum Strategy, emphasizing the need to maintain the country’s globally recognized edge as quantum technologies are expected to grow by 33% over the next five years.

The Enigma of Quantum Mechanics

Quantum mechanics was discovered in the mid-1920s, revealing a microworld riddled with uncertainty. Unlike the familiar uncertainty of daily life, quantum uncertainty denies the existence of a pre-existing reality. Atoms and subatomic particles lack well-defined properties, such as position or speed, in the absence of observation. Measuring an atom’s position, for instance, projects it into a concrete existence from a state of ill-defined positionlessness.

This concept challenges the notion of reality, suggesting that quantum measurements create physical reality rather than merely disclose it. The quantum domain can be visualized as an amalgam of alternative realities, blended into a superposition. For example, an atom might be in many places at once, or moving in multiple directions simultaneously. Erwin Schrödinger, a founder of quantum mechanics, illustrated this with the famous thought experiment of a cat in a box, simultaneously alive and dead until observed.

Einstein’s Challenge and the Rise of Entanglement

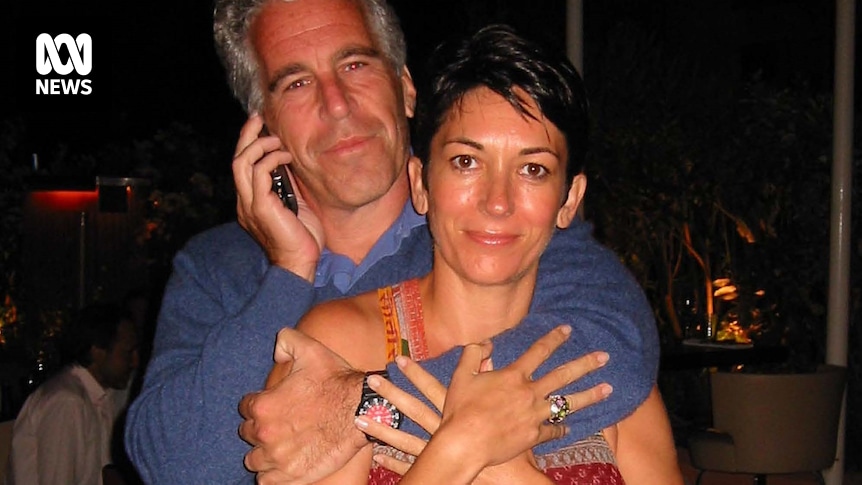

Einstein was skeptical of quantum mechanics, believing in a world of sharply defined properties beneath the quantum blur. He famously stated, “God does not play dice with the universe,” opposing the views of Niels Bohr, who embraced the theory’s peculiarities. In 1935, Einstein, along with Nathan Rosen and Boris Podolsky, proposed an experiment to challenge quantum mechanics, introducing the concept of entanglement.

Entanglement suggests that two particles can remain connected, influencing each other instantaneously across distances. Einstein dismissed this as “spooky action at a distance,” as it seemed to violate relativity, which forbids faster-than-light influences. However, experiments in the 1980s, notably by Alain Aspect, confirmed entanglement, disproving Einstein’s notion of pre-existing reality and establishing entanglement as a critical quantum property.

Quantum Information Science and Technological Frontiers

Entanglement, initially used by Einstein to undermine quantum mechanics, has become a valuable resource in technology. Quantum teleportation, for instance, allows the transmission of quantum bits (qubits) without traversing space, laying the groundwork for a quantum internet. China holds the record for long-range entanglement, having sent an entangled photon 1200 kilometers to a satellite.

Quantum computing, a burgeoning multibillion-dollar industry, exploits quantum states to process information exponentially faster than classical computers. The concept dates back to a 1981 lecture by Richard Feynman, but gained traction in 1994 when Peter Shor demonstrated that a quantum computer could break encryption codes. This spurred a race to develop quantum computers and quantum-proof sensitive data.

Quantum computing’s potential extends beyond code-breaking, with applications in climate modeling, financial analysis, and drug design. Quantum cryptography, leveraging the irreversible nature of quantum measurements, offers secure information transfer. Despite technical challenges, such as the fragility of quantum states, quantum computing promises transformative impacts across industries.

Quantum Sensing and the Future

Quantum sensing, the most advanced branch of Quantum 2.0, exploits the fragility of quantum states to detect external disturbances. Quantum gravity gradiometers, for example, measure minute variations in gravity, aiding industries like construction, mining, and hydrology. Quantum accelerometers offer precise navigation without GPS, crucial for applications vulnerable to jamming.

Quantum clocks, outperforming mechanical counterparts, provide unparalleled accuracy, essential for navigation and timing. Gravitational wave detection, achieved using massive quantum detectors, has opened a new window into cosmic events. In healthcare, quantum sensing promises advancements in diagnostics and brainwave monitoring, with potential applications in controlling prosthetics and robots.

The integration of quantum information science with artificial intelligence (AI) heralds the dawn of Quantum AI (QAI), potentially elevating intelligence to unprecedented levels. While AI’s evolution towards general intelligence remains debated, QAI could lead to “quantum intelligence,” a mind beyond human comprehension. This raises profound philosophical questions about coexisting with such entities.

As Quantum 2.0 technologies advance, the foundational questions of quantum mechanics persist. The many-worlds interpretation, treating quantum superpositions as real parallel worlds, offers one perspective. While Einstein might have resisted, the idea that countless versions of reality exist is gaining traction among physicists.

In the end, whether the Moon exists when nobody is looking remains a philosophical puzzle, with quantum mechanics suggesting a reality far richer and more complex than our everyday experiences. As the field continues to evolve, its implications for science, technology, and society are boundless.