Scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have reached a significant milestone in the realm of quantum technology. By achieving unprecedented control over molecules, they have opened new possibilities for advancements in quantum technology, chemical research, and the exploration of new physics. This breakthrough, detailed in a recent publication in Physical Review Letters, involves manipulating a calcium hydride molecular ion with near-perfect precision.

The achievement marks a leap from the manipulation of obedient atoms to the more complex and unruly molecules. Molecules, unlike atoms, can rotate and vibrate, making them more sensitive to environmental changes such as temperature. As NIST physicist Dietrich Leibfried explains,

“If you’re sensitive to something, it can be a curse, because you would like to not be sensitive, or it can be a blessing. You can use that sensitivity to your advantage.”

Quantum Peekaboo: The Challenge of Molecular Control

Molecules present a unique challenge due to their complex structure and behavior. Unlike a single atom, which can be likened to a simple ball, a molecule such as calcium hydride resembles a lopsided dumbbell. This complexity arises from the molecule’s ability to exist in numerous rotational and vibrational states, as Dalton Chaffee, the lead author of the study, notes,

“To control a particle, we need to pinpoint it in one specific state. A molecule has a large number of states it can be in because of its rotation and vibration.”

To tackle this complexity, NIST physicists employed a technique known as quantum logic spectroscopy. Initially developed to enhance the precision of atomic clocks, this method involves using a calcium ion as a helper to communicate with the molecular ion. The charged calcium hydride molecule and the calcium ion are trapped together, naturally repelling each other like a loaded spring.

While the calcium hydride molecule does not interact well with lasers, the calcium ion does. By cooling the calcium ion with lasers, researchers can slow its motion, which in turn slows the molecule. This cooling process is crucial, as it allows the molecular state to remain unchanged for significantly longer periods than at room temperature.

Observing Quantum Leaps

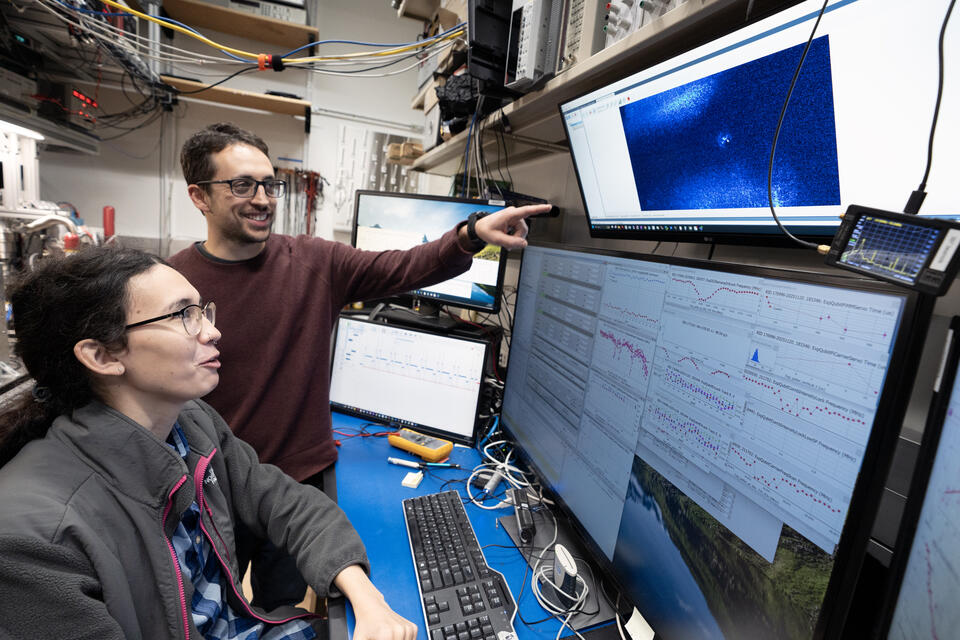

Once the molecule is cooled, researchers use a laser to alter its rotation. Although they cannot directly observe the molecule’s rotation, the calcium ion acts as an indicator. When the molecule’s rotation changes, the calcium ion emits a tiny flash of photons, visible as a bright dot. This double flash signifies two quantum leaps, or state changes, within the molecule.

Baruch Margulis, a NIST postdoctoral fellow, describes the satisfaction of witnessing quantum mechanics in action,

“That’s quantum mechanics. In our lab, we can see with the camera if our ion is in one quantum state or another, which I find super cool. It’s captivating to see it with your own eyes.”

The molecule can maintain its rotational state for approximately 18 seconds before thermal radiation forces a state change, ceasing the ion’s flashes. This duration allows researchers thousands of opportunities to measure the molecule’s state, providing a robust demonstration of control with a 99.8% success rate.

Implications for Quantum Technology and Beyond

This breakthrough has far-reaching implications. The experiment demonstrated that molecules could serve as microscopic thermometers, offering more accurate readings of thermal radiation than conventional thermometers. Such quantum thermometers could enhance atomic clocks by mitigating the effects of thermal radiation fluctuations.

Furthermore, precise molecular control opens the door to a vast array of molecular species for quantum technologies. While current quantum computing and sensing technologies primarily utilize a limited selection of charged atoms, the techniques developed by NIST are adaptable to other molecules. This adaptability could revolutionize fields such as quantum sensing, quantum information science, and chemical studies.

As Margulis points out,

“It’s not just a one-off, but it’s a demonstration of a protocol that can be used for many other molecules. When you think about a periodic table, it has a finite number of elements. Molecules are more diverse. So, although they are hard to control, there’s a huge pool of molecules. If you had perfect control, you could select a candidate based on which technology you’re interested in.”

While the path to fully harnessing molecular control remains long, the NIST team’s achievement represents a pivotal step forward. As scientists continue to refine these techniques, the potential for groundbreaking discoveries in quantum technology and beyond grows ever closer.