There is a significant and unresolved tension in cosmology concerning the rate at which the universe is expanding. Resolving this could potentially unveil new physics. Astronomers are continually seeking innovative methods to measure this expansion, in case unknown errors exist in data from traditional indicators like supernovae. Recently, researchers, including those from the University of Tokyo, have measured the universe’s expansion using novel techniques and fresh data from the latest telescopes. Their approach leverages the way light from extremely distant objects travels multiple pathways to reach us. Differences in these pathways enhance models of events on the largest cosmological scales, including expansion.

The universe is vast, and it is expanding. But how vast is it? The exact size remains unknown. However, the rate of its expansion is measurable. It’s not straightforward, as the expansion appears faster the further away we observe. For every 3.3 million light years (or one megaparsec) from us, objects seem to be moving away at increasing multiples of about 73 kilometers per second. This rate of expansion, known as the Hubble constant, is 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/s/Mpc).

New Methods in Measuring Cosmic Expansion

There are various methods to determine the Hubble constant, but traditionally, these have relied on “distance ladders” such as supernovae or Cepheid variable stars. These objects are considered well-understood enough to provide accurate distance measurements, even in other galaxies. Over decades, these observations have increasingly constrained the Hubble constant. However, doubts about this method persist, making cosmologists eager for improvements. In their latest paper, a team of astronomers, including Project Assistant Professor Kenneth Wong and postdoctoral researcher Eric Paic from the University of Tokyo’s Research Center for the Early Universe, successfully demonstrated a method known as time-delay cosmography. This technique aims to reduce reliance on distance ladders and could have implications in other cosmological areas as well.

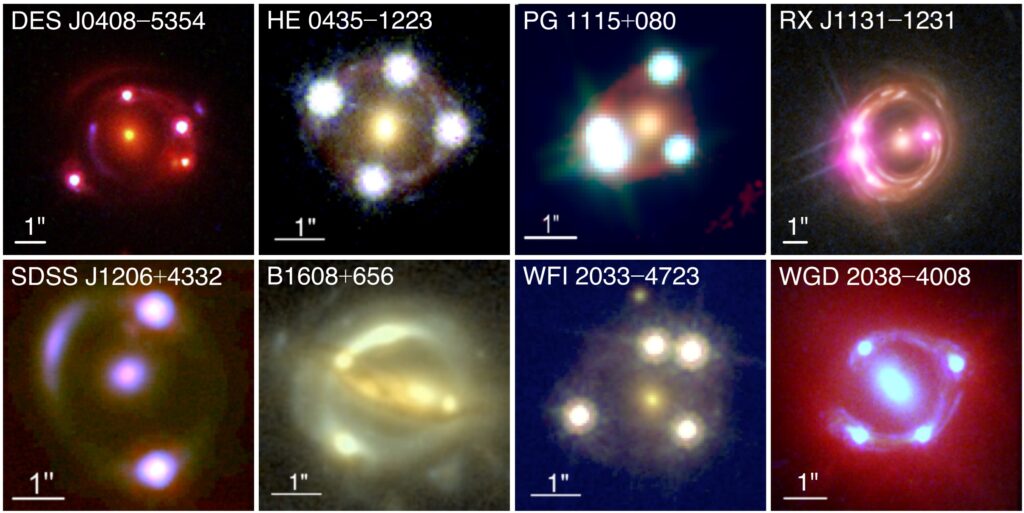

“To measure the Hubble constant using time-delay cosmography, you need a really massive galaxy that can act as a lens,” said Wong. “The gravity of this ‘lens’ deflects light from objects hiding behind it around itself, so we see a distorted version of them. This is called gravitational lensing. If the circumstances are right, we’ll actually see multiple distorted images, and each will have taken a slightly different pathway to get to us, taking different amounts of time. By looking for identical changes in these images that are slightly out of step, we can measure the difference in time they took to reach us. Coupling this data with estimates on the distribution of the mass of the galactic lens that’s distorting them is what allows us to calculate the acceleration of distant objects more accurately. The Hubble constant we measure is well within the ranges supported by other modes of estimation.”

Understanding the Hubble Tension

The quest to find a precise Hubble constant is not just academic. It is crucial for understanding the universe’s history, which remains unresolved. The value of 73 km/s/Mpc for the Hubble constant is consistent with observations of nearby objects. However, other methods, such as analyzing the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—the radiation from the Big Bang—yield a lower value of 67 km/s/Mpc. This discrepancy is known as the Hubble tension. The work of Wong, Paic, and their collaborators helps clarify this tension, as there remains doubt about whether it is merely due to experimental error.

“Our measurement of the Hubble constant is more consistent with other current-day observations and less consistent with early-universe measurements. This is evidence that the Hubble tension may indeed arise from real physics and not just some unknown source of error in the various methods,” said Wong. “Our measurement is completely independent of other methods, both early- and late-universe, so if there are any systematic uncertainties in those methods, we should not be affected by them.”

Future Directions and Implications

“The main focus of this work was to improve our methodology, and now we need to increase the sample size to improve the precision and decisively settle the Hubble tension,” said Paic. “Right now, our precision is about 4.5%, and in order to really nail down the Hubble constant to a level that would definitively confirm the Hubble tension, we need to get to a precision of around 1-2%.”

The team is optimistic that such precision gains are achievable. The current study utilized eight time-delay lens systems, each obscuring a distant quasar—a supermassive black hole accreting gas and dust, causing it to shine brightly—and new data from the latest space-based and ground-based telescopes, including the James Webb Space Telescope. The team plans to increase the sample size and improve various measurements to rule out any unaccounted systematic errors.

“One of the largest sources of uncertainty is the fact that we don’t know exactly how the mass in the lens galaxies is distributed. It is usually assumed that the mass follows some simple profile that is consistent with observations, but it is hard to be sure, and this uncertainty can directly influence the values we calculate,” said Wong. “The Hubble tension matters, as it may point to a new era in cosmology revealing new physics. Our project is the result of a decades-long collaboration between multiple independent observatories and researchers, highlighting the importance of international collaboration in science.”

This development follows years of research and collaboration, representing a significant step forward in understanding the universe’s expansion. As astronomers continue to refine their methods and expand their datasets, the potential for groundbreaking discoveries in cosmology looms large, promising a deeper understanding of the cosmos and its origins.