Irvine, Calif., Jan. 22, 2026 — Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, in collaboration with Jefferson Health in Philadelphia, have unveiled critical differences in the structural and functional causes of mitral valve stenosis. This condition, which restricts blood flow through the heart, has been traditionally understood through a singular lens. However, the new findings suggest that current diagnostic approaches may need reevaluation to better serve an expanding patient demographic.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, utilized advanced 3D ultrasound heart imaging alongside patient-specific laboratory modeling. This innovative approach revealed that stenosis resulting from mitral annular calcification (MAC) is structurally and functionally distinct from rheumatic mitral stenosis, the latter being the basis for many existing diagnostic standards.

Reevaluating Diagnostic Approaches

The research indicates that employing diagnostics tailored for rheumatic disease might lead to underestimations or mischaracterizations of MAC-related mitral stenosis. This could significantly impact clinical decision-making and treatment strategies. Mitral annular calcification affects approximately 8 to 15 percent of the general population, predominantly older adults, those with chronic kidney disease, and individuals with a history of chest radiation.

Despite its prevalence, MAC-related mitral stenosis has not been thoroughly characterized and is often assessed using frameworks developed for rheumatic heart disease. This is problematic, given the substantial differences between the two conditions, particularly concerning valve structure and blood flow constraints.

Innovative Research Methodology

The research team, led by senior co-author Arash Kheradvar, a professor at UC Irvine, adopted a two-phase strategy to explore these differences. Initially, they analyzed 3D transesophageal echocardiography data from 70 patients, comparing healthy mitral valves with those affected by MAC-related and rheumatic mitral stenosis.

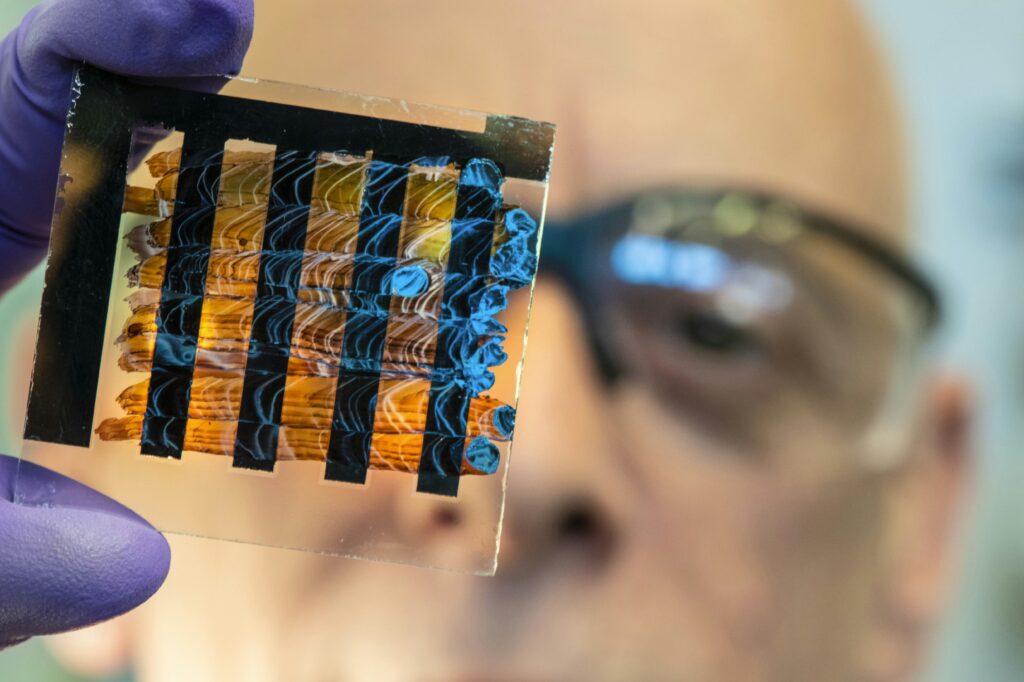

In the second phase, they employed 3D printing to create patient-specific silicone models of healthy, rheumatic, and MAC-affected valves. These models were evaluated in a heart flow simulator replicating human heart conditions. This controlled environment allowed researchers to isolate the impact of valve geometry on blood flow and pressure gradients, factors that are challenging to discern in routine clinical imaging.

“For decades, mitral stenosis has been assessed using a one-size-fits-all approach,” said Arash Kheradvar. “But MAC-related stenosis behaves differently. The valve structure is different and blood flow patterns are different, and the relationship between anatomy and severity doesn’t follow the same rules.”

Key Findings and Clinical Implications

Compared with rheumatic mitral stenosis, MAC-related stenosis demonstrated several distinct characteristics:

- Smaller overall valve dimensions and reduced valve volume.

- Distinct leaflet motion and apically displaced hinge points.

- Disproportionately high pressure gradients across the valve.

- Greater kinetic energy loss during blood flow.

- Unique flow behavior despite a relatively larger geometric orifice area.

“What’s striking is that patients with MAC-related stenosis can appear to have a reasonably sized opening on imaging yet experience pressure gradients and energy losses that indicate much more severe obstruction,” said Gregg Pressman, Jefferson Health professor of medicine.

The findings underscore the need for clinicians to exercise caution when applying rheumatic-based diagnostic thresholds to patients with MAC-related mitral stenosis. The study advocates for disease-specific diagnostic criteria and management guidelines, which could inform future transcatheter and surgical therapies tailored for MAC-related stenosis.

Broader Implications and Future Directions

Beyond its impact on the mitral valve, MAC is recognized as a marker of broader cardiovascular risk, associated with adverse outcomes such as stroke and increased mortality. The detailed structural and flow characterization from this study may pave the way for more precise interventional strategies that account for the distinct anatomy and hemodynamics of calcification-driven stenosis.

The study’s first author, Mohammad Saber Hashemi, now an assistant professor at Kansas State University, conducted this research as a postdoctoral scholar at UC Irvine. The work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

As the medical community continues to grapple with the complexities of heart valve diseases, this research represents a significant step forward in understanding and treating mitral valve stenosis. The implications of these findings may extend beyond individual patient care, potentially influencing broader diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in cardiology.