CHICAGO – A groundbreaking study has revealed that the brain’s waste-clearing system, known as the glymphatic system, significantly declines in function with repeated head impacts. This research, focusing on cognitively impaired professional boxers and mixed martial arts fighters, will be presented at the upcoming annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Sports-related traumatic brain injuries contribute to up to 30% of all brain injury cases, with boxing and mixed martial arts being significant contributors. Repeated head impacts are known risk factors for neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, raising concerns about the long-term health of athletes in these sports.

Understanding the Glymphatic System

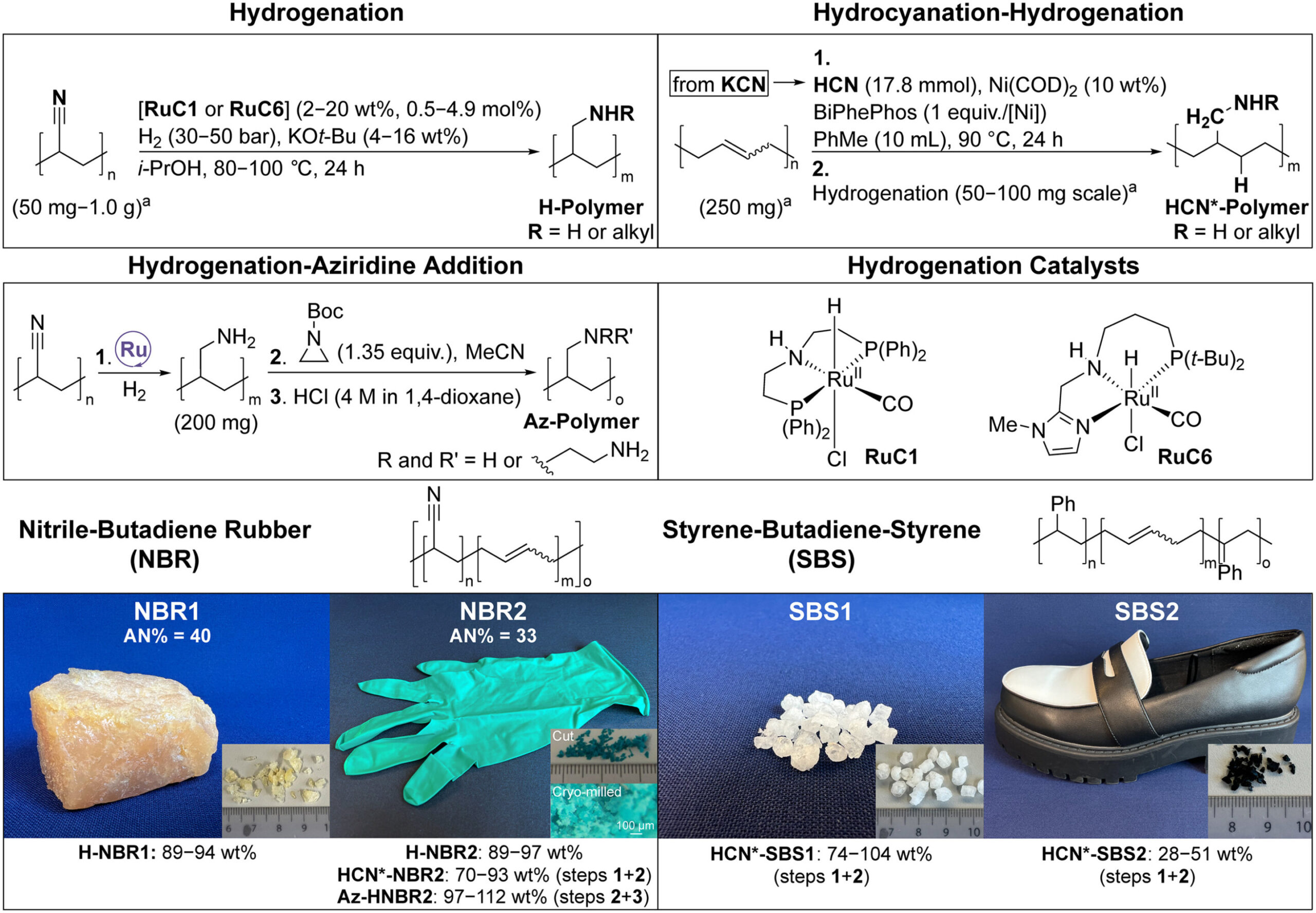

The glymphatic system is a network of fluid-filled channels that plays a crucial role in clearing waste products from the brain. It is often compared to the lymphatic system in other parts of the body. “The recently discovered glymphatic system is like the brain’s plumbing and garbage disposal system,” explained Dr. Dhanush Amin, the lead author of the study conducted by researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Cleveland Clinic Nevada. “It’s vital for helping the brain flush out metabolites and toxins.”

Diffusion tensor imaging along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) is a specialized MRI technique used to measure and analyze water movement in and around the spaces that surround the channels of the glymphatic system. These spaces are essential for regulating fluid balance, transporting nutrients and immune cells, and protecting the brain from damage.

Research Findings and Implications

The study utilized the DTI-derived ALPS index, a non-invasive biomarker that assesses glymphatic function. An impaired DTI-ALPS index can indicate cognitive decline and is associated with conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. “When this system doesn’t work properly, damaging proteins can accumulate, which have been linked to Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia,” noted Dr. Amin, now an assistant professor of neuroradiology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

The researchers analyzed baseline data from Cleveland Clinic’s Professional Athletes Brain Health Study (PABHS), a longitudinal study involving approximately 900 active fighters. The study included data from 280 fighters, 95 of whom were cognitively impaired at baseline, alongside 20 demographically matched healthy controls.

“We thought repeated head impacts would cause lower ALPS in cognitively impaired fighters compared to non-impaired fighters,” Dr. Amin said. “We also expected the ALPS measurement to be significantly correlated with the total number of knockouts in the impaired fighters.”

Contrary to their hypothesis, the researchers observed a significantly higher glymphatic index among impaired fighters that deteriorated over time with the total number of knockouts. In athletes with continued trauma, glymphatic function significantly declined.

Brain’s Response to Trauma

“We believe that the glymphatic index was initially high in the impaired athlete group because the brain initially responds to repeated head injuries by ramping up its cleaning mechanism, but eventually, it becomes overwhelmed,” Dr. Amin explained. “After a certain point, the brain just gives up.” Non-impaired fighters had a significantly lower right and total glymphatic index compared to impaired fighters. The relationship between the glymphatic index and knockout history was markedly different between the two groups.

Dr. Amin emphasized the importance of understanding the impact of repeated head impacts on the glymphatic system for the early detection and management of neurodegenerative risks in contact sport athletes. “If we can spot glymphatic changes in the fighters before they develop symptoms, then we might be able to recommend rest or medical care or help them make career decisions to protect their future brain health,” he said.

Looking Ahead

The findings of this study could have significant implications for the management of athletes in contact sports. By identifying changes in the glymphatic system early, there is potential to intervene before irreversible damage occurs. This could lead to new guidelines for rest periods, medical care, and even career decisions for athletes at risk.

Co-authors of the study include Gaurav Nitin Rathi, M.S., Charles Bernick, M.D., and Virendra Mishra, Ph.D. As the research community continues to explore the intricacies of the glymphatic system, the hope is that these insights will pave the way for better protective measures and treatment options for athletes worldwide.