PROVIDENCE, R.I. — A groundbreaking study from Brown University has identified specific brain regions that exhibit heightened activity in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) during tasks requiring significant cognitive effort. This discovery holds promise for refining treatment approaches and assessment methods for OCD.

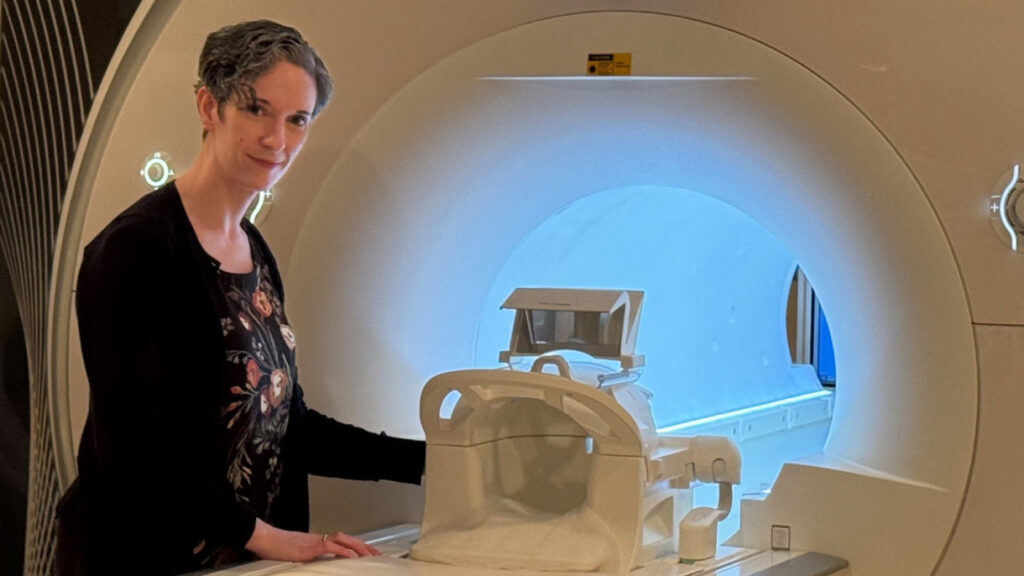

Published in the journal Imaging Neuroscience, the research was spearheaded by the team in Theresa Desrochers’ laboratory at Brown University’s Carney Institute for Brain Science. Desrochers, an associate professor of brain science and psychiatry, focuses her research on abstract sequential behavior, a type of behavior that follows a general sequence, such as dressing, despite variations in individual steps.

Linking Abstract Sequencing to OCD

The study explored potential connections between abstract sequencing and OCD, a prevalent psychiatric disorder characterized by intrusive thoughts and compulsive actions. “We started looking into OCD because symptoms of the condition suggest that patients lose track or get stuck where they are while performing sequences,” explained Hannah Doyle, the lead study author and a postdoctoral research associate in Desrochers’ lab.

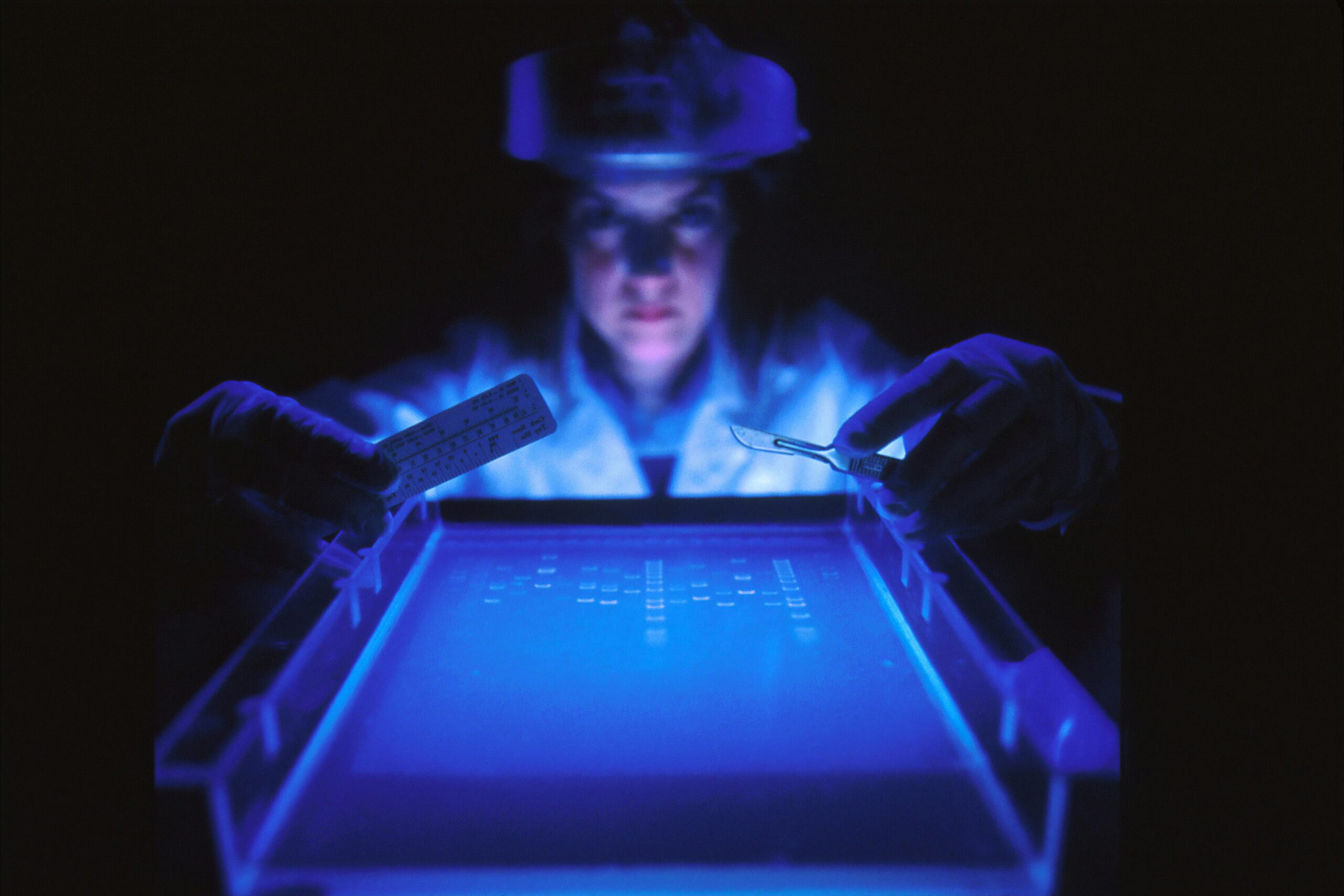

Participants were asked to perform a sequential cognitive task while undergoing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This task involved naming the color or shape of objects in a specific order. Although individuals with OCD performed the task comparably to a control group, MRI scans revealed distinct differences in brain regions related to motor and cognitive task control, working memory, and object recognition.

“Their behavior looked similar, but the brains of the participants with OCD recruited more brain regions than the people in the control group,” Doyle noted.

Uncovering New Brain Regions Associated with OCD

Intriguingly, some brain regions identified in the study had not been previously linked to OCD. These include the middle temporal gyrus, which plays a role in working memory, semantic memory retrieval, and language processing, as well as a region encompassing the occipital gyrus and the temporo-occipital junction, involved in visual stimulus processing and object recognition.

Nicole McLaughlin, a study co-author and an associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown, emphasized the potential implications of these findings. As a neuropsychologist at Butler Hospital, McLaughlin highlighted that these insights could lead to new treatment targets, particularly involving transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

Implications for Future OCD Treatments

TMS, a non-invasive procedure that uses magnetic pulses to stimulate specific brain regions, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an OCD treatment in 2018. Research indicates that TMS can lead to improvements in approximately 30-40% of OCD patients. The identification of new brain regions involved in OCD could enhance the efficacy of TMS by targeting these areas more precisely.

According to McLaughlin, “The findings may lead to new treatment targets for OCD, especially when involving transcranial magnetic stimulation.”

Looking Ahead: The Future of OCD Research and Treatment

This study represents a significant step forward in understanding the neural underpinnings of OCD. By identifying previously unassociated brain regions, researchers can develop more targeted therapies, potentially increasing the effectiveness of existing treatments like TMS.

As research continues, the hope is that these insights will not only improve treatment outcomes but also lead to a deeper understanding of OCD’s complex nature. Future studies may explore how these brain regions interact with other parts of the brain and contribute to the disorder’s symptoms, paving the way for innovative therapeutic approaches.

Ultimately, the study underscores the importance of continued research in the field of psychiatric disorders, emphasizing the potential for neuroscience to transform mental health treatment.