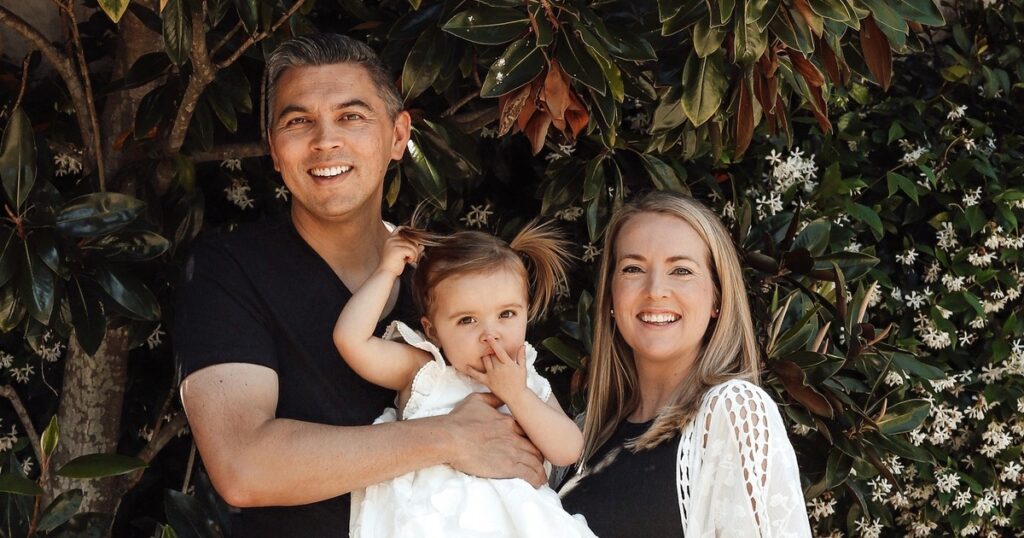

During a routine visit to her GP, new mother Marcelle Cooper was asked about her six-month-old baby girl. Replying that everything was great and she was loving motherhood, Marcelle was masking her real struggles, aware as she was speaking that she couldn’t bring herself to tell the truth. At home with her baby Skye the next day, she realized something was seriously wrong.

“I was bawling my eyes out, and I thought, ‘That was my golden opportunity, why did I not say something then to my GP?’” Marcelle told newsGP. “So, I picked up the phone and called the surgery, and told the receptionist, ‘This is urgent – I am a struggling new mother, and I’m in a really dark place. Can you please have the GP call me back?’”

That phone call marked a turning point in Marcelle’s journey with postnatal anxiety and depression, having mustered the strength to disclose what she was experiencing and seek the support she needed. The first three months after Skye was born, Marcelle describes as blissful – both mother and baby were well, with Skye meeting all her milestones. But a significant change around the 12-week mark brought uncontrollable crying “for no particular reason,” and she began to feel consumed by insomnia, a lack of appetite, and debilitating anxiety.

The Struggle with Postnatal Anxiety

“I felt a panic feeling when my husband would leave the house in the morning, and I knew I was going to be alone with the baby for the entire day and didn’t know what I was going to do with her,” Marcelle said. “And a real sense of overthinking, so even with simple everyday decisions I would overthink then it felt like no matter what decision I would make, it was going to disadvantage me, and the decision I’d make would be the wrong one. It was a really awful feeling because I felt like I couldn’t be the mother this beautiful baby deserves.”

Having seen her GP regularly throughout her fertility journey, which included years of trying to conceive and several miscarriages, Marcelle battled on her own with this anxiety and depression for the first three months after her baby was born.

Seeking Help and Finding Support

“Finally, I had the courage to tell my GP, ‘I’m a wreck, I’m not coping, and I was too ashamed to tell you,’ and she could tell straight away it was serious … and talked me through some of my options,” she said. “It was an instant sense of, ‘I’m not alone in this anymore,’ and having someone else to speak to about my feelings and my thoughts that wasn’t family, because I didn’t want to burden my family because they were trying so hard to support me already.”

As well as a mental health assessment plan and discussion around medication options, Marcelle’s GP referred her to the Gidget Foundation which offered 10 free sessions with a perinatal depression and anxiety specialist clinician. Starting with fortnightly appointments, Marcelle began to feel the weight lift and realization she had the support she needed.

“I felt like I was the only person in the world who had these thoughts and experiences, so knowing there was a network of professionals trained to help me was a real sense of relief,” she said. “That was an eye opener for me, because I thought, maybe I’m not the only person who feels this crazy.”

Understanding the Broader Context

Recent, yet-to-be-published data from the Gidget Foundation reveals that more than a quarter of Australian parents are unsure of what mental health support is available to them during the perinatal period, while a third believe their mental health symptoms are not severe enough to seek professional help. Perinatal depression and anxiety affects around one in five mothers and one in 10 fathers, impacting almost 100,000 parents each year.

“GPs can regularly enquire about the mental wellbeing of both parents during the pregnancy and the postnatal period,” said Dr. Ka-Kiu Cheung, Chair of RACGP Specific Interests Antenatal and Postnatal Care. “Framing these conversations as part of routine health checks can be helpful, and GPs can reassure families that adjustment to bringing home a newborn can include feelings of anxiety or mood changes – and that this is common.”

Dr. Cheung adds that GPs’ role in routine screening is aided by their regular contact with not just the parents, but usually the newborn in the first few months of life. “We can monitor how families bond and cope and provide information on both social and health supports. If mental health concerns are identified, GPs can screen for red flags whilst putting in place supports, offering treatment choices and providing referrals as required.”

A Call for Early Intervention

Now a proud Gidget Foundation ambassador, Marcelle is a lived experience advocate for early intervention and support during the perinatal and postnatal period. And while she recognizes now that recovery begins with talking, she wishes she’d asked for help sooner.

“I was putting on a very brave face for a very long time,” she said. “Knowing that if GPs are there with open minds and it’s taken a lot of courage for their patients to come and ask for help – just being taken seriously is really important. I’m very grateful for my GP, she’s been amazing.”

For GPs and other healthcare professionals – obstetricians, midwives or anyone in contact with potential, expectant and new parents – Marcelle has a simple ask to have on their radar to identify at-risk patients. “I often wonder if it was standard procedure I would have done these sessions, I would have spoken to a professional,” she said. “But because it was optional, by saying, ‘I need help’ it was almost like I was a failure, accepting defeat. I was too ashamed to accept that I couldn’t cope. And I wonder if I had had the support earlier, if my outcomes after Skye was born would be quite different because I would have been armed with the tools.”