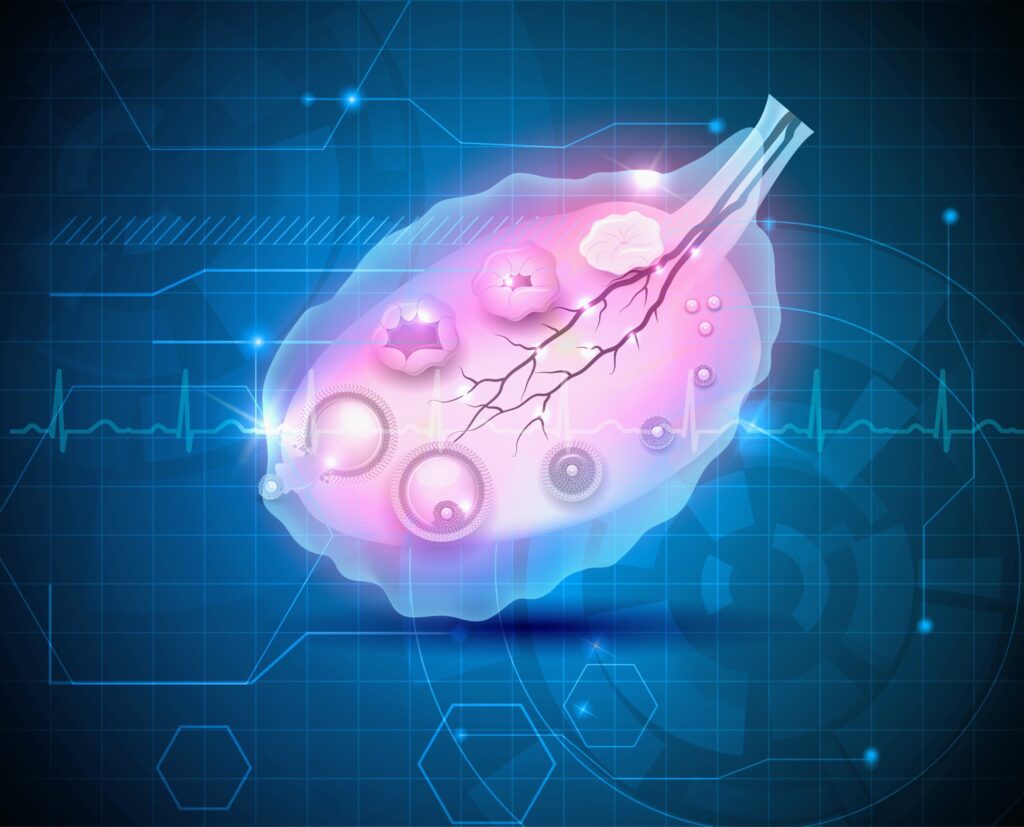

For decades, the prevailing belief among scientists was that fertility declines primarily because eggs age and deteriorate. However, groundbreaking research from the University of California, San Francisco, and the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub reveals a more complex narrative. This study uncovers the intricate biological ecosystem within the ovary, highlighting how its aging impacts fertility and overall health.

The research team discovered that the ovary is far more than a mere repository for eggs. It is a dynamic environment of cells, nerves, and tissues that interact and influence each other. This hidden network plays a critical role in how eggs mature and how the ovary itself ages over time.

Understanding Ovarian Aging

Utilizing advanced imaging and gene sequencing techniques, researchers examined ovaries in both humans and mice. Dr. Diana Laird, senior author and professor at UCSF, explained,

“We’ve long thought of ovarian aging as simply a problem of egg quality and quantity. What we’ve shown is that the environment around the eggs – the supporting cells, nerves, and connective tissue – is also changing with age.”

This revelation has implications that extend beyond reproduction. As the ovary ages and slows down, it can trigger a cascade of changes in other organs, potentially leading to increased risks of heart disease, bone loss, and metabolic issues post-menopause. The research team aims to leverage these insights to develop strategies that could extend both fertility and overall health.

Visualizing the Living Ovary

To delve deeper into the aging process, the researchers developed a novel 3D imaging technique that allows them to observe the entire ovary without dissection. This approach brought the ovary to life in vivid color and detail. In young mice, eggs were evenly distributed throughout the tissue. However, older mice exhibited fewer eggs and faced challenges with conception, even with in vitro fertilization. In humans, eggs clustered into small “pockets” surrounded by empty zones, which thinned over time.

Dr. Laird noted,

“This was a surprise – we assumed eggs would be distributed more evenly based on what we see in the developing ovary. These pockets suggest that even within one ovary, the environment around an egg may influence how long it lasts and how well it matures.”

Cellular Changes and Aging

The team conducted single-cell sequencing on nearly 100,000 ovarian cells from mice and humans, identifying 11 main cell types, including glia, a type of support cell typically found in the brain. Fibroblasts and endothelial cells, crucial for structural integrity and blood flow, showed significant age-related changes, appearing inflamed and scarred in older samples.

Interestingly, scarring in the ovaries appeared much earlier than in other organs like the lungs or liver, suggesting that ovarian aging begins subtly, long before menopause. Norma Neff, Ph.D., director of the Genomics Platform at the Biohub, emphasized,

“By combining the Laird lab’s cutting-edge imaging with the Biohub’s expertise in two kinds of single-cell sequencing, we were able to understand the ovary in unprecedented detail.”

The Nervous System’s Role

An unexpected finding was the presence of dense networks of sympathetic nerves, which regulate the body’s “fight or flight” response, within the ovaries. These nerve networks increased with age. Experiments showed that blocking these nerves in mice resulted in more dormant eggs but fewer maturing ones, indicating that nerves play a role in egg activation.

Glial cells appeared to guide and protect these nerve fibers, forming a communication system within the ovary. This network may provide insights into how stress, hormones, and aging are interconnected over time.

Comparative Insights: Mice and Humans

Despite differences, mice and humans shared many ovarian characteristics. Both species exhibited the same basic cell types, though humans showed stronger fibrosis and nerve growth with age. Dr. Laird remarked,

“Until now, it was somewhat unclear whether we could use mice as a model for humans when it comes to the ovaries – we have quite different reproductive windows. But the similarities we saw in this study make us confident that we can move forward in mice and apply those lessons to humans.”

These comparisons are crucial for determining when animal studies can accurately reflect human fertility and when they cannot.

Future Directions in Ovarian Health

This study redefines the understanding of ovarian life, illustrating that the organ is not merely running out of eggs but is evolving as an ecosystem. The interactions between cells, nerves, and hormones are constant, and when one component weakens, the entire system is affected.

Eliza Gaylord, Ph.D., co-first author of the study, suggested,

“The fountain of youth may actually be the ovary. Delaying ovarian aging could promote healthier aging overall.”

By mapping out these cellular connections, researchers hope to maintain the ovarian environment, potentially unlocking longer fertility and improved health throughout life.

The study is published in the journal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.