(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – December 22, 2025) A groundbreaking study from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital has unveiled how different ligands, or protein-binding chemicals, can variably activate G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). These findings, published today in Nature, could significantly impact the development of drugs targeting these crucial proteins, which include a third of all FDA-approved medications.

GPCRs are pivotal in transmitting signals from outside to inside cells, primarily through G proteins, influencing vital processes such as growth, metabolism, and neurotransmitter signaling. Despite their importance, the complexity of how different ligands affect the same GPCR has long puzzled scientists, hindering drug development. The study highlights that the speed at which ligands, known as agonists, push the mu-opioid receptor through its activation steps explains their varied effects.

Understanding the Kinetic Trap

The concept of a kinetic trap is central to this discovery. It refers to intermediate shapes that a GPCR adopts during activation, which require significant energy to overcome. The study likens this to a small ball rolling down a hill, slowed by a divot, while a larger ball rolls uninterrupted. This analogy illustrates how different agonists navigate the kinetic traps at varying speeds, despite reaching the same end state.

“We found that for partial agonists of a GPCR, the system slows down as it gets stuck in specific steps while changing conformations during activation,” said Georgios Skiniotis, PhD, director of the St. Jude Center of Excellence for Structural Cell Biology.

These insights were achieved by capturing ‘molecular movies’ of drugs affecting the mu-opioid receptor, a well-known GPCR targeted by pain management drugs like morphine and codeine. These findings could lead to the development of more effective pain relievers, addressing the ongoing opioid crisis.

Capturing Molecular Dynamics

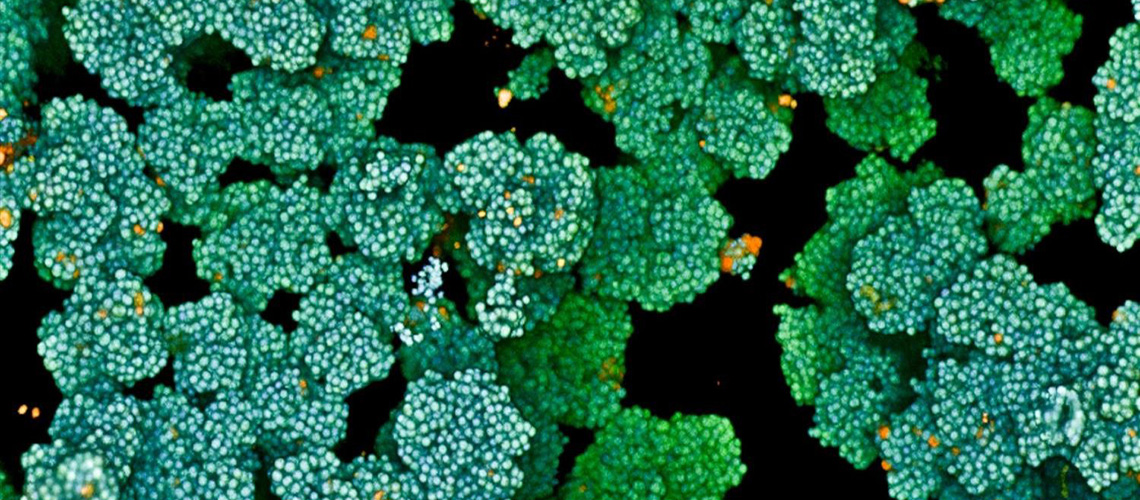

Researchers used cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) to obtain images of G-protein activation over time. By comparing partial, full, and super agonists of the mu-opioid receptor, they observed that partial agonists remained stuck in a kinetic trap longer than their more potent counterparts.

“Super and full agonists pushed through to G-protein dissociation quickly, but partial agonists spent longer in a pseudo-stable form before G-protein release,” Skiniotis explained.

This mechanism was corroborated by single-molecule imaging, conducted in collaboration with Scott Blanchard, PhD, director of the St. Jude Single-Molecule Imaging Center. The study demonstrated that full and super agonists enable the GPCR to be more dynamic, quickly overcoming energy barriers, while partial agonists result in a more rigid structure.

Implications for Drug Development

The implications of these findings are profound. By understanding how different agonists affect GPCR activation, researchers can engineer next-generation drugs that maximize safety and efficacy. This could revolutionize treatments for conditions ranging from pain management to metabolic disorders.

“We showed that different agonists act like different people pushing a sticky dimmer switch,” Skiniotis said. “All are moving it from off to on, but those of higher strength are pushing it faster, while those of lower strength get slowed or ‘trapped’ along the way.”

The study’s authors include Makaia Papasergi-Scott and Maria Claudia Peroto from Stanford University, and Arnab Modak, Miaohui Hu, and Ravi Kalathur from St. Jude, among others. The research was supported by grants from the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Collaborative Research Consortium on GPCRs, the National Institutes of Health, and the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas.

As the scientific community digests these findings, the potential for new, more effective drugs looms large, promising advancements in medical treatments that could transform lives.