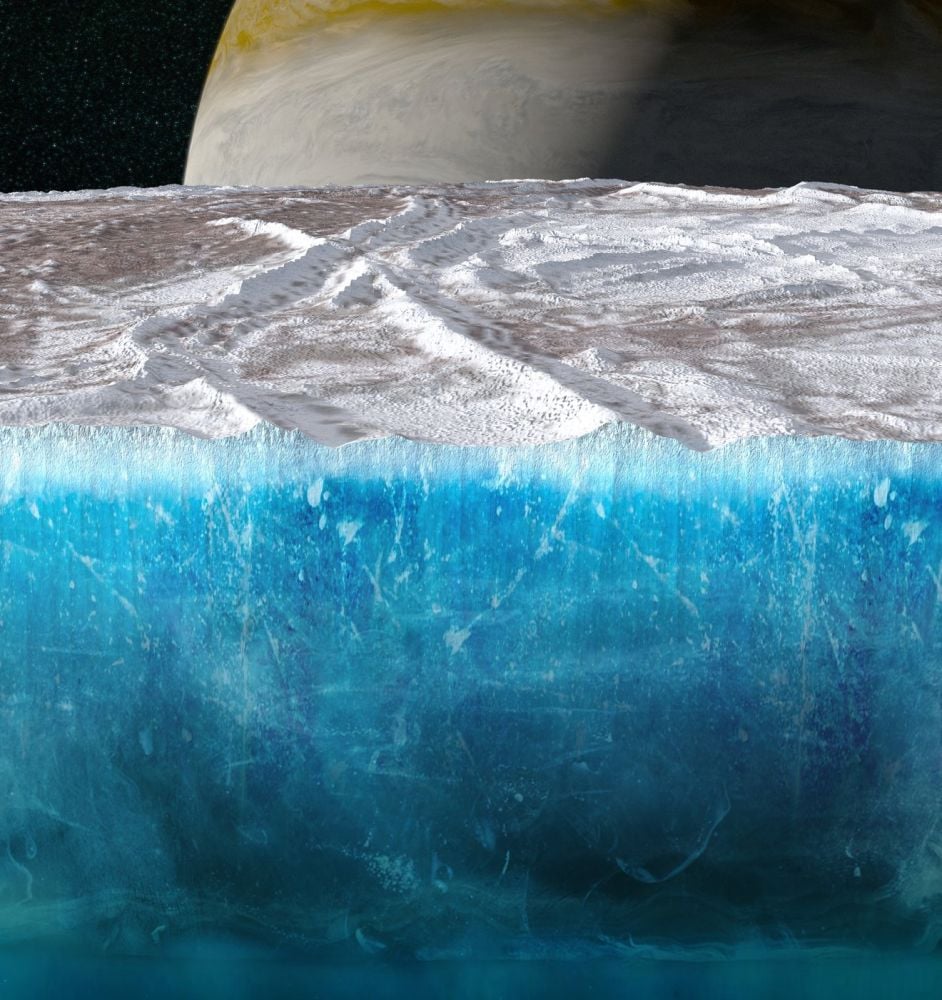

Recent observations of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa have revealed a thick ice shell covering a warm, chemically-rich ocean, sparking significant interest in its potential for hosting life. This has made Europa a prime target for exploration, with NASA’s Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency’s JUICE missions poised to investigate the moon in greater detail.

Speculation about Europa’s subsurface ocean dates back to the Voyager missions, which captured images of the moon’s cracked icy surface. These images led scientists to hypothesize the existence of a hidden ocean. Subsequent missions, including Galileo and observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, provided further evidence, such as plumes of water vapor erupting through the ice, suggesting a dynamic subsurface ocean.

Challenges in Understanding Europa’s Ice Shell

Despite these promising observations, many questions remain about Europa’s habitability. One key question concerns the thickness of its ice shell and the nature of the fissures and cracks within it. Scientists believe that for Europa’s ocean to support life, there must be pathways through the ice allowing for chemical exchange between the ocean and the surface.

Europa’s surface is bombarded by Jupiter’s intense radiation, driving chemical reactions that could produce life-supporting substances. If the ice is thin or contains fissures acting as chemical conduits, these substances could potentially reach the ocean.

Charged particles from Jupiter strike Europa’s surface, splitting frozen water molecules and potentially allowing oxygen to reach the subsurface ocean, enabling life.

New Findings from Juno’s Observations

While the Europa Clipper and JUICE missions are still years away, NASA’s Juno spacecraft has been studying the Jovian system, including Europa, for nearly a decade. Recent research published in Nature Astronomy presents findings from Juno’s observations, led by Steve Levin from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The study, titled “Europa’s ice thickness and subsurface structure characterized by the Juno microwave radiometer,” utilized Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) to probe Europa’s ice. The MWR, with its six antennae, measures ice temperatures at varying depths, providing insights into the ice shell’s thickness and the nature of its fissures.

Estimates of Europa’s ice-shell thickness range from 3 km to over 30 km, with evidence of subsurface cracks, faults, and pores.

The MWR’s measurements suggest that Europa’s ice shell could be as thick as 29 ± 10 km, with cracks and pores extending hundreds of meters below the surface. These findings imply that the ice may be a more formidable barrier to chemical exchange than previously thought.

Implications for Europa’s Habitability

The new data suggests that Europa’s thick ice shell could hinder the exchange of life-supporting chemicals between the surface and the ocean. This revelation dampens some of the enthusiasm about Europa’s habitability. Other research indicates that the observed plumes might originate from pockets of water within the ice rather than the ocean itself, further questioning the ocean-surface connection.

However, the possibility of life on Europa is not entirely ruled out. Life could still exist, relying on tidal heating and hydrothermal vents, with its ocean seeded with nutrients during formation. Without active chemical exchange, sustaining life would be challenging once the ocean’s nutrients are depleted.

“How thick the ice shell is and the existence of cracks or pores within the ice shell are part of the complex puzzle for understanding Europa’s potential habitability,” said study co-author Scott Bolton.

Future Exploration and Research

The Europa Clipper and JUICE missions will provide crucial data to further our understanding of Europa. The Europa Clipper, equipped with ice-penetrating radar, will map the boundary between the ocean and ice, offering a near-global view through nearly 50 close flybys. JUICE, while focused on multiple moons, will also contribute with its radar observations during Europa flybys.

The Europa Clipper is scheduled to arrive in 2030, followed by JUICE in 2031. These missions are expected to yield significant insights into Europa’s ice shell and its potential for habitability, helping scientists answer long-standing questions about this intriguing moon.