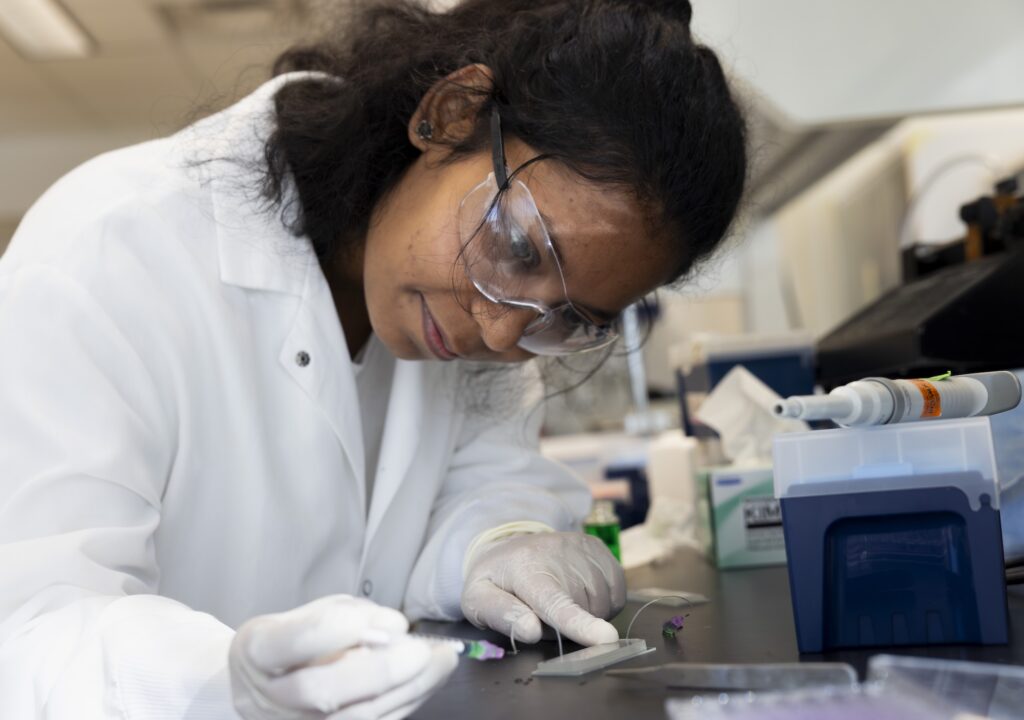

Abha Kumari, Chemical Engineering Doctoral Student, injects a sample into a micro-fluid chip used for capturing vesicles from Glioblastoma patients while at the Biointerfaces Institute located in the North Campus Research Complex in Ann Arbor, MI on November 19, 2025. Researchers at Northwestern Medicine and the University of Michigan, led by Michigan Engineering’s Sunitha Nagrath, are developing a diagnostic chip that can be used to confirm the effectiveness of chemotherapy on brain cancer patients. The chip collects cancer tumor vesicles that can show whether cancer cells died during chemotherapy infusion. The new technique could help patients with the brain cancer glioblastoma decide whether to continue with a particular chemotherapy drug, switch drugs or stop treatment. Photo: Jeremy Little/Michigan Engineering, Communications & Marketing

Researchers at Northwestern Medicine and the University of Michigan have developed a groundbreaking diagnostic chip that can determine the effectiveness of chemotherapy for brain cancer through a simple blood test. This innovative approach could significantly impact the treatment of glioblastoma, a notoriously aggressive brain cancer, by allowing doctors to assess treatment success after just one dose.

The study, published in Nature Communications, demonstrates that by opening the blood-brain barrier, tumor content can leak into the bloodstream, enabling the monitoring of chemotherapy effectiveness via blood draws. This advancement could help in deciding whether to continue, switch, or halt chemotherapy treatments for glioblastoma patients.

Revolutionizing Glioblastoma Treatment

Glioblastoma is a devastating diagnosis, with most patients succumbing to the disease within two years. The tumor infiltrates the brain, making complete surgical removal impossible, and the blood-brain barrier often prevents chemotherapy drugs from reaching the tumor site. However, the new diagnostic chip offers a potential lifeline by providing real-time feedback on treatment efficacy.

“Instead of waiting months, after one dose we can know if a given treatment is working,” said Dr. Adam Sonabend, a neurosurgeon at Northwestern Medicine and co-corresponding author of the study. “That is huge for glioblastoma patients. It could potentially prevent patients from getting prolonged treatments that are ineffective, thus also avoiding unnecessary side effects.”

Innovative Technology and Methodology

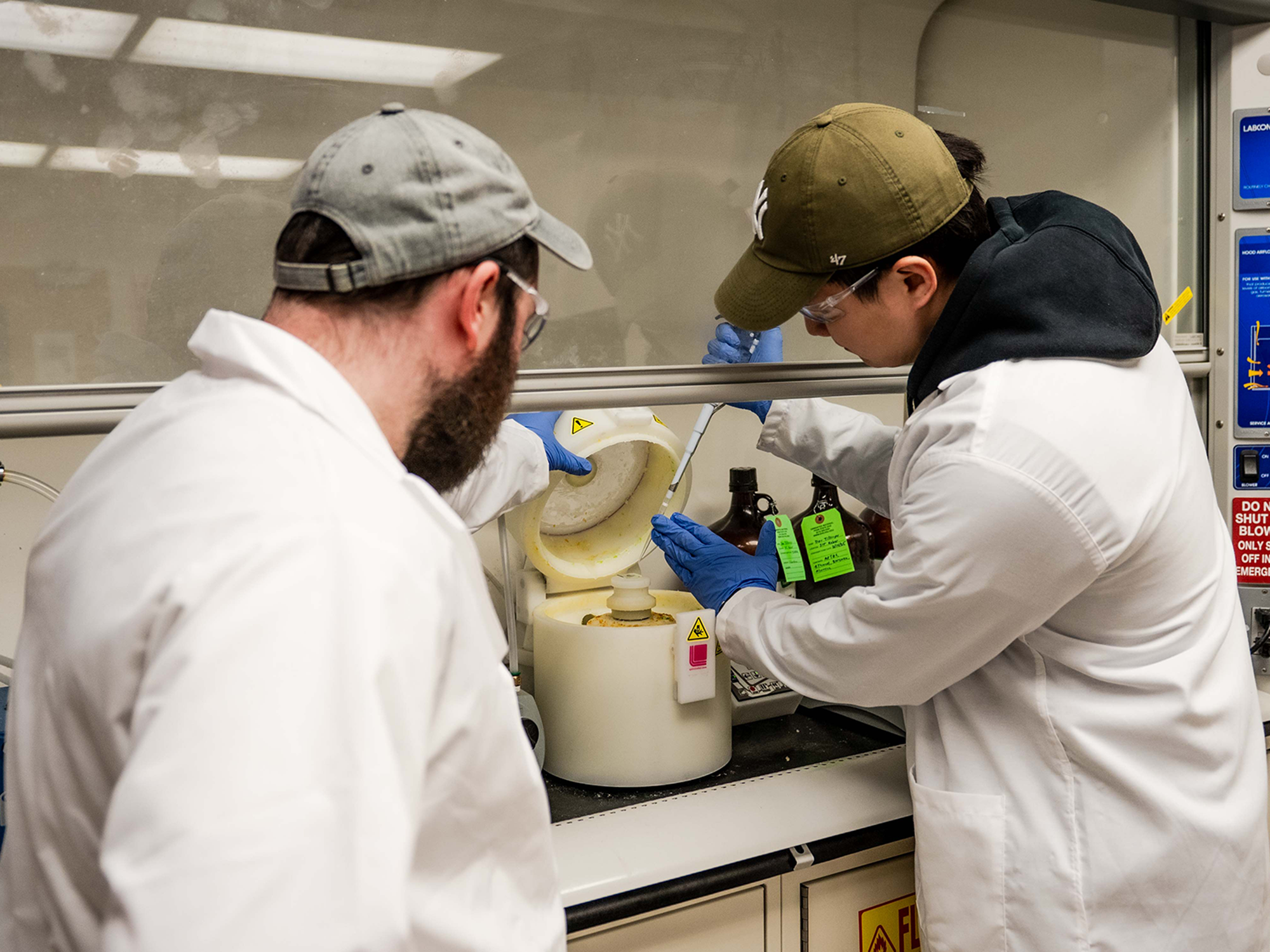

The research involved using the SonoCloud-9, a therapeutic ultrasound device from Carthera in Lyon, France, to temporarily open the blood-brain barrier. This allowed the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel to penetrate the tumor site. The study further tested a diagnostic technology from the University of Michigan that captures extracellular vesicles and particles (EVPs) from cancer cells.

“There are tiny particles floating in patient blood, called extracellular vesicles, that have been released by the cancer cells,” explained Sunitha Nagrath, the Dwight F. Benton Professor of Chemical Engineering at U-M. “These particles act as messengers, carrying special bits of genetic tumor material and proteins.”

Cells use extracellular vesicles and particles for communication, and EVPs can be hijacked for disease progression. It is exciting to be a part of this technology that can successfully leverage EVPs for monitoring treatment response in tumors.

The Michigan team developed the GlioExoChip, which isolates EVPs from blood plasma, turning blood draws into “liquid biopsies.” This method allows researchers to calculate a ratio of extracellular vesicles before and after chemotherapy, indicating treatment success or failure.

Implications for Future Cancer Treatments

Mark Youngblood, a neurosurgery resident at Northwestern Medicine and co-first author of the study, highlighted the potential of this technology: “The GlioExoChip provides a quick and minimally invasive way to monitor treatment response in a disease where MRI scans often give misleading results.”

The research team plans to validate their findings with other glioblastoma therapies and explore the use of extracellular vesicles in assessing treatments for other cancers. The study received support from various institutions, including the National Institutes of Health, the Lou and Jean Malnati Brain Tumor Institute, and the U.S. Department of Defense.

As the team seeks patent protection and partners to bring this technology to market, the potential for transforming cancer treatment monitoring is significant. This development represents a promising step forward in the fight against one of the deadliest forms of brain cancer.