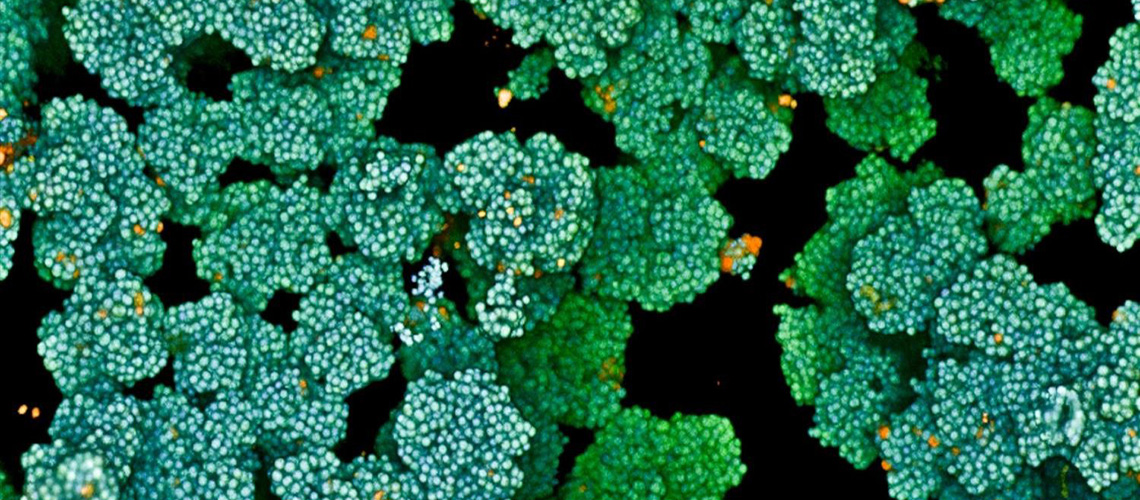

All neurons start from the same DNA blueprint, yet they develop distinct characteristics in the brain and body. A new study from MIT reveals that differences in gene transcription into RNA are crucial in determining neuron types. The research further uncovers that individual cells edit specific RNA sites at varying rates, offering new insights into neural biology.

The study, published in eLife, examined RNA editing across more than 200 individual cells, focusing on tonic and phasic motor neurons of the fruit fly. Contrary to previous assumptions of “all-or-nothing” editing, the findings indicate that most sites are edited at intermediate rates. This revelation could reshape our understanding of RNA editing’s role in neural function, according to senior author Troy Littleton, the Menicon Professor at MIT.

Exploring the Landscape of RNA Editing

Led by Andres Crane, PhD ’24, the research team delved into the RNA editing landscape of neurons, identifying hundreds of edits across numerous genes. From a genome of approximately 15,000 genes, they documented “canonical” edits at 316 sites in 210 genes, facilitated by the enzyme ADAR, which is also present in mammals.

Of these edits, 175 were found in protein-coding regions, with 60 likely altering amino acids significantly. Additionally, 141 edits occurred in non-coding areas, potentially impacting protein production levels. The discovery of “non-canonical” edits, not made by ADAR, suggests the presence of other enzymes involved in RNA editing, potentially opening new avenues for genetic therapies.

“In the future, if we can begin to understand in flies what the enzymes are that make these other non-canonical edits, it would give us broader coverage for thinking about doing things like repairing human genomes where a mutation has broken a protein of interest,” Littleton says.

Developmental Significance and Neuronal Individuality

The study also highlighted RNA edits specific to juvenile fly larvae, suggesting developmental significance. By examining full gene transcripts of individual neurons, the researchers identified previously undocumented editing targets. This finding underscores the potential for RNA editing to influence developmental processes.

Interestingly, the study observed that neurons of the same type could exhibit significant individuality in RNA editing. Some neurons showed nearly 100% editing at certain sites, while others displayed none. On average, any given site was edited about two-thirds of the time, with most edits falling between 20% and 70%.

“The vast majority of editing events we found were somewhere between 20 percent and 70 percent,” Littleton notes. “We were seeing mixed ratios of edited and unedited transcripts within a single cell.”

Implications for Neural Function and Future Research

One of the critical questions arising from this research is how RNA edits impact cellular function. Littleton’s lab previously investigated two edits in the gene complexin, which regulates neurotransmitter release. They discovered that different edit combinations produced various protein versions, significantly affecting synaptic activity.

The current study identifies 13 more edits in complexin, yet to be explored. Another protein of interest is Arc1, which experienced a non-canonical edit. Arc1 is crucial for synaptic plasticity, the ability of neurons to adjust synapse strength in response to activity, a process vital for learning and memory. Notably, Arc1 editing fails in fruit fly models of Alzheimer’s disease.

Littleton’s lab is now focused on understanding the functional implications of these RNA edits in fly motor neurons. This research could pave the way for advancements in genetic therapies and deepen our understanding of neural plasticity.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, The Freedom Together Foundation, and The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory. In addition to Crane and Littleton, authors include Michiko Inouye and Suresh Jetti.