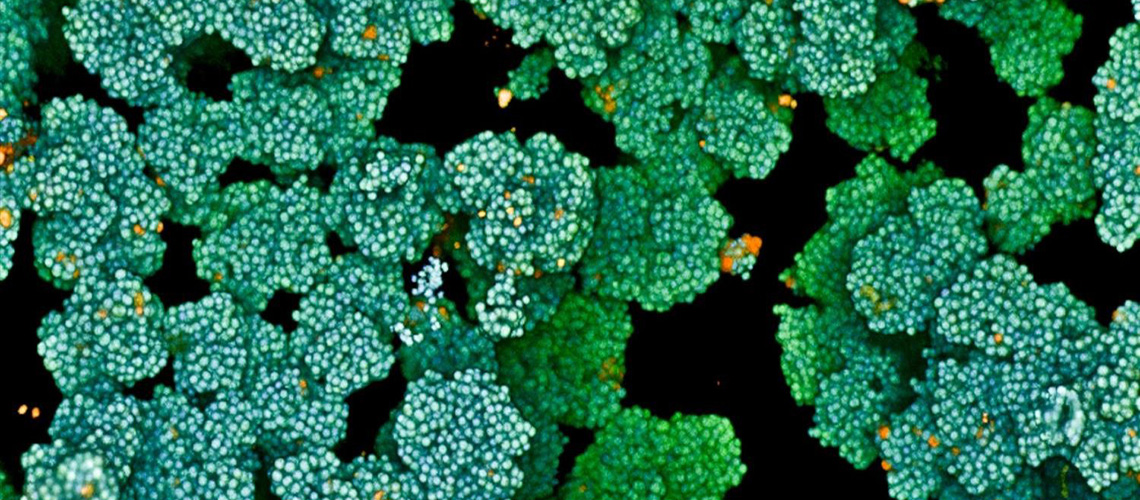

During the earliest stages of development, tissues and organs form through the dynamic processes of cell shifting, splitting, and growth. A team of engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has now devised a method to predict, minute by minute, the behavior of individual cells during the initial growth phase of a fruit fly embryo. This breakthrough, detailed in a study published today in Nature Methods, could pave the way for predicting the development of more complex tissues and organisms, and potentially aid in identifying cell patterns linked to early-onset diseases like asthma and cancer.

The MIT team introduced a deep-learning model that learns and predicts changes in the geometric properties of individual cells as a fruit fly develops. By analyzing videos of developing fruit fly embryos, each beginning as a cluster of approximately 5,000 cells, the model demonstrated a 90 percent accuracy rate in forecasting how these cells fold, shift, and rearrange during the first hour of development.

Revolutionizing Developmental Biology

This new approach is spearheaded by Ming Guo, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. “This very initial phase is known as gastrulation, which takes place over roughly one hour, when individual cells are rearranging on a time scale of minutes,” Guo explains. “By accurately modeling this early period, we can start to uncover how local cell interactions give rise to global tissues and organisms.”

The research team envisions extending their model to predict cell-by-cell development in other species, such as zebrafish and mice, to identify common patterns across species. Moreover, the method holds promise for discerning early disease patterns. For instance, the development of lung tissue in asthma patients, which differs significantly from healthy tissue, could be better understood through this model.

Dual-Graph Model: A New Approach

Traditionally, scientists have modeled embryo development in one of two ways: as a point cloud, where each point represents a cell, or as a “foam,” where cells are depicted as bubbles that slide against each other. Guo and his colleague Haiqian Yang, an MIT graduate student, decided to integrate these approaches into a “dual-graph” model.

“There’s a debate about whether to model as a point cloud or a foam,” Yang notes. “But both are essentially different ways of modeling the same underlying graph, which is an elegant way to represent living tissues. By combining these as one graph, we can highlight more structural information, like how cells are connected to each other as they rearrange over time.”

This dual-graph structure allows for a detailed representation of developing embryos, capturing properties such as the location of a cell’s nucleus and its interactions with neighboring cells.

High-Quality Data: The Key to Success

The researchers applied their model to high-quality videos of fruit fly gastrulation provided by collaborators at the University of Michigan. These videos, which capture the development of fruit flies at single-cell resolution, are rare and provide crucial data for training the model.

After training the model with data from three fruit fly embryo videos, the team tested it on a new video and achieved high accuracy in predicting cell changes. “We end up predicting not only whether these things will happen, but also when,” Guo says. “For instance, will this cell detach from this cell seven minutes from now, or eight? We can tell when that will happen.”

Future Implications and Challenges

The potential applications of this model extend beyond fruit flies. The researchers believe it could predict the development of other multicellular systems, including human tissues and organs. However, the availability of high-quality video data remains a significant challenge.

“From the model perspective, I think it’s ready,” Guo asserts. “The real bottleneck is the data. If we have good quality data of specific tissues, the model could be directly applied to predict the development of many more structures.”

This groundbreaking work, supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, represents a significant advancement in developmental biology and offers exciting possibilities for future research and medical applications.