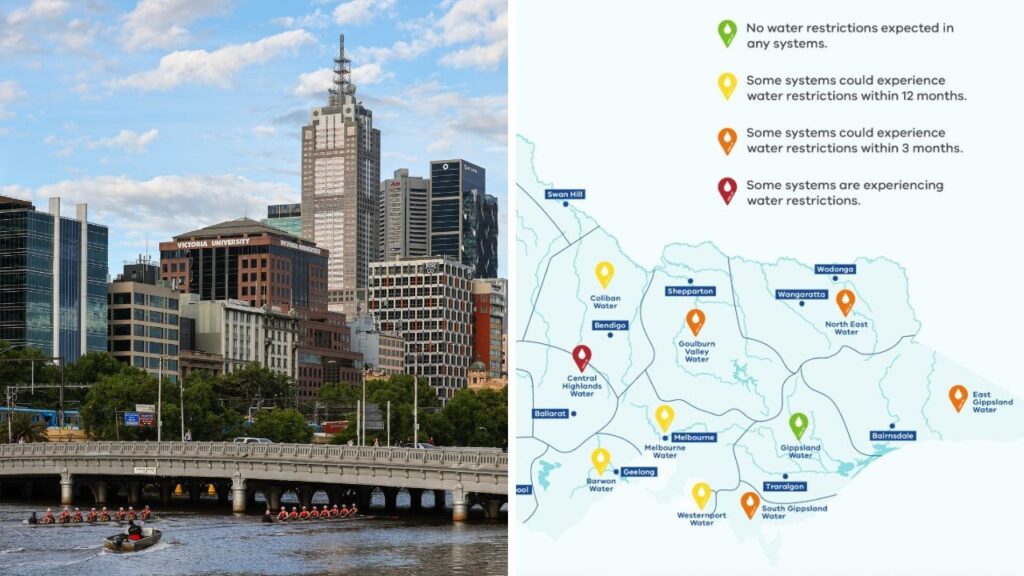

Melbourne is on the brink of a water crisis as population growth and the rise of data centers place unprecedented pressure on the city’s water supply. According to the state government’s Annual Water Outlook, Victoria experienced lower-than-average rainfall in 2025, leading to historically low water reserves. This month, major storage facilities across the state were only 61 percent full, a stark contrast to the 80 percent recorded at the same time in 2024.

Melbourne’s water storage levels have dropped to 76 percent capacity, marking a 12 percent decrease from the previous year. These levels would have been even lower if not for the government’s decision to order 50 billion liters of desalinated water from the Victorian Desalination Plant, which converts seawater into drinking water near Wonthaggi. Despite this intervention, the report warns that if dry weather persists, Melbourne and Geelong could face “severe” water restrictions by 2026, even with the desalination plant operating at full capacity.

Population Growth and Data Centers: A Double-Edged Sword

The water crisis comes as Victoria grapples with a resurgence in population growth following a period of decline during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the year leading up to June, the state experienced a net gain of 123,000 people, primarily due to overseas migration. Melbourne, now home to 5.4 million residents, is growing at a faster rate than Sydney in percentage terms.

Compounding the issue is the burgeoning demand from data centers, driven by the rise of artificial intelligence applications such as ChatGPT. These facilities, particularly those focused on AI, generate significant heat and require vast amounts of water for cooling, most of which is lost through evaporation. While some centers, like Firmus’ planned AI factory in Tasmania, utilize closed-loop cooling systems that do not rely on local water supplies, these remain exceptions.

In July, Greater Western Water was reviewing 19 applications from data centers that would collectively consume almost 19 billion liters of water annually—equivalent to the yearly usage of 330,000 Melburnians.

Saul Kavonic, head of energy research at MST Macquarie, noted that the sudden demand from data centers caught state governments “on the back foot.” He stated, “Policy makers appear to have not adequately planned for rising water demand from population growth, let alone new demand from data centers.”

Exploring Solutions: Desalination and Beyond

In response to the growing crisis, Water Minister Gayle Tierney has released a Water Security Plan supported by an expert task force. The plan includes considering an $840 million expansion of the Victorian Desalination Plant, which would allow the facility to add 50 billion liters of water to the system. Additionally, the task force is exploring the possibility of constructing a second facility in Melbourne’s west.

However, not everyone agrees that desalination is the optimal solution. Tim Fletcher, a professor of urban ecohydrology at the University of Melbourne, advocates for alternative approaches. “There are many better solutions to the problem,” he said, emphasizing the importance of planning for sustainable solutions well in advance of crises.

“There’s not a shortage of water, it’s just about using it effectively,” Fletcher explained. “There are billions of liters being generated by all these new surfaces, and we could be collecting that water.”

Fletcher argues that harnessing stormwater is a more cost-effective and environmentally friendly option. Unlike desalination, which is energy-intensive and demands significant electricity from an already strained grid, stormwater collection addresses issues such as erosion and flooding while providing a valuable water source.

The Path Forward: Balancing Growth and Sustainability

The challenge for Melbourne and Victoria at large is to balance the demands of a growing population and a thriving tech industry with the sustainable management of natural resources. As the state government weighs its options, the need for comprehensive planning and investment in water infrastructure becomes increasingly urgent.

While the Allan government has yet to commit to upgrading the Victorian Desalination Plant, a report by Oxford Economics Australia suggests that such work could begin in 2030 and conclude by 2034. Meanwhile, experts like Fletcher continue to advocate for innovative solutions that prioritize sustainability over short-term fixes.

As Melbourne navigates this complex landscape, the decisions made today will shape the city’s future resilience and its ability to support both its residents and its burgeoning tech sector.