Approximately 445 million years ago, a cataclysmic event reshaped life on Earth. During this brief geological period, glaciers formed over the supercontinent Gondwana, desiccating the vast, shallow seas and ushering in an ‘icehouse climate.’ This dramatic shift in climate and ocean chemistry led to the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction (LOME), wiping out about 85% of marine species, which constituted the majority of Earth’s life at the time.

In a recent study published in Science Advances, researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) have revealed that this mass extinction event gave rise to an unprecedented diversity of vertebrate life. According to the study, jawed vertebrates emerged as the dominant group during this period of upheaval, setting the stage for the evolution of modern vertebrates. “We have demonstrated that jawed fishes only became dominant because this event happened,” stated Professor Lauren Sallan of the Macroevolution Unit at OIST. “And fundamentally, we have nuanced our understanding of evolution by drawing a line between the fossil record, ecology, and biogeography.”

A Glimpse into the Ordovician World

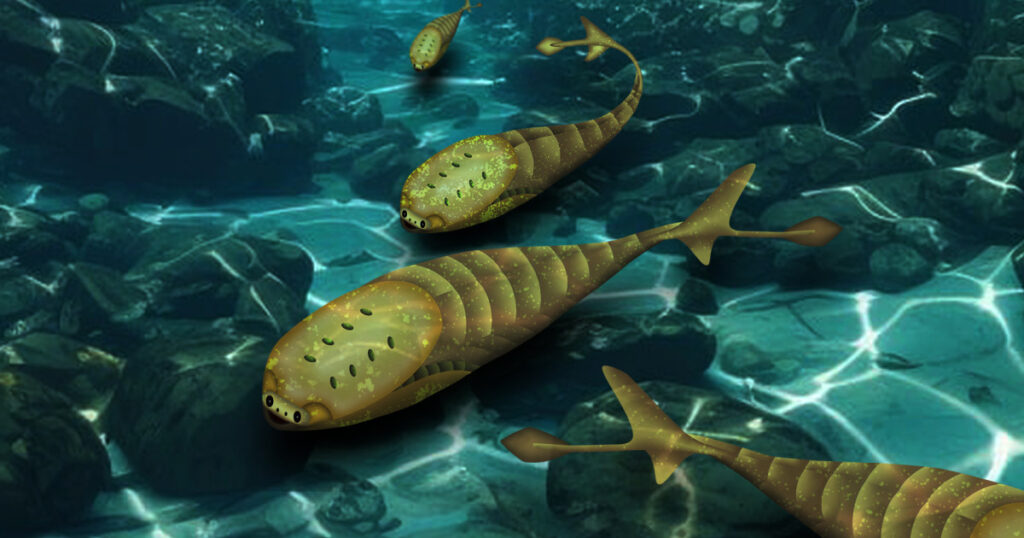

The Ordovician period, spanning from roughly 486 to 443 million years ago, presented a vastly different Earth. Dominated by the southern supercontinent Gondwana, the planet was surrounded by extensive shallow seas. The poles were free of ice, and the warm waters supported a greenhouse climate. Coastal regions were being slowly colonized by primitive plants and arthropods, while the oceans teemed with diverse and peculiar life forms.

Among these were large-eyed, lamprey-like conodonts, towering sea sponges, trilobites, and human-sized sea scorpions. Giant nautiloids with pointy shells patrolled the waters, preying on smaller creatures. Amidst these bizarre inhabitants were the early ancestors of gnathostomes, or jawed vertebrates, which would eventually rise to prominence.

The Impact of the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

While the ultimate causes of LOME remain uncertain, its impact is clearly documented in the fossil record. The extinction unfolded in two pulses: initially, the planet transitioned rapidly from a greenhouse to an icehouse climate, covering Gondwana with glaciers and drying up shallow ocean habitats. A few million years later, as biodiversity began to recover, the climate reversed, melting ice caps and flooding marine life with warm, sulfuric, and oxygen-depleted waters.

During and after these extinction pulses, surviving vertebrates found refuge in isolated biodiversity hotspots, known as refugia, separated by vast, deep oceans. These refugia provided a sanctuary for gnathostomes, giving them a competitive edge. “We pulled together 200 years of late Ordovician and early Silurian paleontology,” explained Wahei Hagiwara, the study’s first author and current OIST PhD student. “By creating a new database of the fossil record, we reconstructed the ecosystems of the refugia and quantified the genus-level diversity of the period. The trend is clear—the mass extinction pulses led directly to increased speciation after several millions of years.”

Tracing the Evolutionary Path of Vertebrates

The researchers constructed a comprehensive database of fossils from around the world, linking the rise in gnathostome biodiversity to LOME and geographical location. “This is the first time we’ve been able to quantitatively examine the biogeography before and after a mass extinction event,” noted Prof. Sallan. Hagiwara added, “For example, in what is now South China, we see the first full-body fossils of jawed fishes directly related to modern sharks. They were concentrated in these stable refugia for millions of years until they evolved the ability to cross open oceans to other ecosystems.”

By integrating the fossil record with biogeography, morphology, and ecology, the study provides new insights into evolutionary processes. “Did jaws evolve to create a new ecological niche, or did our ancestors fill an existing niche first and then diversify?” asked Prof. Sallan. “Our study points to the latter. Confined to geographically small areas with many open niches left by extinct jawless vertebrates and other animals, gnathostomes could suddenly occupy a wide range of different niches.” This pattern is reminiscent of Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands, which diversified their diet and evolved beak shapes to better suit their ecological niches.

Ecological Reset and the Rise of Jawed Vertebrates

While jawed fishes thrived in South China, their jawless counterparts continued to evolve elsewhere, dominating the wider seas for the next 40 million years. These jawless vertebrates diversified into various forms of reef fishes, some with alternative mouth structures. However, the reasons why jawed fishes eventually came to dominate remain a mystery.

The researchers discovered that LOME did not simply erase existing ecosystems but instead triggered an ecological reset. Early vertebrates occupied the niches left vacant by conodonts and arthropods, reconstructing similar ecological structures with new species. This recurring ‘diversity-reset cycle,’ as the team describes it, illustrates how evolution restores ecosystems by converging on the same functional designs after extinction events.

Prof. Sallan concluded, “By integrating location, morphology, ecology, and biodiversity, we can finally see how early vertebrate ecosystems rebuilt themselves after major environmental disruptions. This work helps explain why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates ultimately prevailed, and why modern marine life traces back to these survivors rather than earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites. Revealing these long-term patterns and their underlying processes is one of the exciting aspects of evolutionary biology.”