TARTU, Estonia — New research from the University of Tartu reveals that medications prescribed years ago may still be influencing the bacteria living in your gut today. This groundbreaking study challenges the long-held belief that drug effects cease once treatment ends.

Researchers analyzed gut bacteria samples from 2,509 Estonian participants and found that various medications leave detectable fingerprints on the microbiome long after discontinuation. Beta-blockers, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, and benzodiazepines showed effects lasting for years, with some changes visible three or more years after last use.

The gut microbiome, a collection of trillions of bacteria in the digestive system, plays a crucial role in digestion, immunity, and overall health. Alterations to this ecosystem can impact everything from nutrient absorption to infection susceptibility.

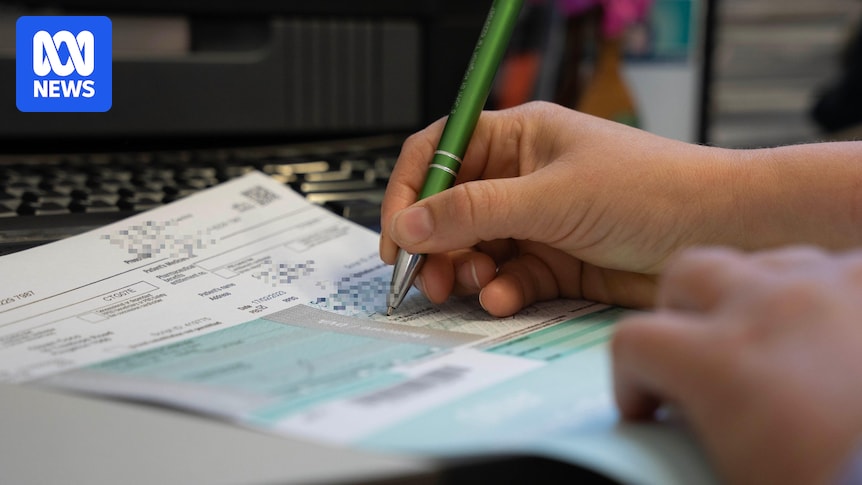

Tracking Medication History Through Electronic Health Records

The research team leveraged detailed electronic health records, a resource often lacking in microbiome studies, to track prescription histories over a five-year period. This allowed them to correlate past medication use with current gut bacteria composition.

Participants who had used certain drugs more than one, two, three, or even four years before providing stool samples were compared with those who hadn’t used those drugs in the preceding five years. Despite modest size, the differences were consistent across drug classes.

Out of 186 medications analyzed, 167 were associated with changes in the gut microbiome when actively used. Notably, 78 of them—roughly 42 percent—displayed “carryover effects” lasting beyond the treatment period.

Beta-Blockers and Anxiety Medications Leave Lasting Marks

While antibiotics predictably left long-term effects, medications targeting human biology rather than bacteria also had surprisingly durable impacts. Beta-blockers, prescribed for high blood pressure and heart conditions, were linked to gut bacteria changes detectable years after cessation. Benzodiazepine derivatives like Xanax and Valium, used for anxiety and sleep disorders, showed similar persistence.

Antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and proton pump inhibitors, commonly used for acid reflux, also demonstrated carryover effects. An “additive” pattern emerged, suggesting that medication history compounds over time rather than dissipating post-treatment.

Anxiety Drugs Rival Antibiotics in Gut Health Impacts

Benzodiazepines stood out, with gut bacteria composition effects rivaling those of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Alprazolam had a broader impact than diazepam, despite treating similar conditions.

Variations were also observed within medication classes. Among beta-blockers, metoprolol caused stronger microbiome changes than nebivolol. Among proton pump inhibitors, omeprazole showed different patterns compared to pantoprazole or esomeprazole. Such differences could eventually influence clinical prescribing decisions.

Which Bacterial Species Are Most Affected

Specific bacterial species exhibited consistent patterns across multiple drug classes. Members of the Clostridiales order increased among people taking beta-blockers, macrolide antibiotics, biguanides like metformin, and proton pump inhibitors.

Proton pump inhibitors were linked to increases in oral bacteria like Streptococcus parasanguinis and Veillonella parvula, which can colonize the gut when stomach acid is reduced. This finding aligns with previous research and helps explain why PPIs sometimes lead to gut infections.

Many medications were negatively correlated with overall bacterial diversity. Participants taking more unique medications had lower microbial richness, meaning fewer different bacterial species.

Researchers analyzed a subset of 328 people who provided stool samples twice, about four years apart. Observing changes when medications were started or stopped confirmed a likely causal relationship between drug use and microbiome alterations.

Why This Matters for Gut Health Research

The study has significant implications for microbiome research. Scientists need to consider not just current medication use, but also prescriptions from months or years earlier to avoid confusing medication effects with disease effects.

Researchers demonstrated this by showing that several disease-microbiome associations were confounded by long-term drug usage. When past medication history was accounted for, some apparent disease signals disappeared.

For clinical medicine, the findings raise questions about the cumulative effects of medications over time. If drugs leave lasting marks on the microbiome, and if the microbiome influences health, then today’s medication decisions could have far-reaching consequences.

The study also suggests that gut bacteria might not fully recover after antibiotic courses. Participants who had used antibiotics years earlier still showed lower bacterial diversity than those who avoided antibiotics during the five-year observation window.

While conducted in Estonia, the medications analyzed are globally used. Beta-blockers, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, and benzodiazepines rank among the most commonly prescribed drugs worldwide.

The research doesn’t suggest stopping prescribed medications, as they treat serious conditions and their health benefits generally outweigh potential microbiome disruptions. However, the findings indicate that medication effects are more layered and longer-lasting than previously recognized.

Future research will need to determine whether these microbiome changes have functional health consequences and explore ways to minimize long-term impacts while maintaining therapeutic benefits.

Disclaimer: This article summarizes peer-reviewed research and is intended for general informational purposes only. It should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before making medication or treatment changes.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The study analyzed shotgun metagenomic sequencing data from 2,509 participants in the Estonian Microbiome Cohort, ages 23 to 89. Researchers linked microbiome data with electronic health records, tracking medication purchases over five years before stool sample collection. A subset of 328 participants provided a second sample after approximately four years, allowing analysis of medication initiation and discontinuation effects. Multiple statistical approaches identified drug-microbiome associations while controlling for age, gender, and body mass index.

Results

Of 186 medications analyzed, 167 (89.8%) were associated with changes in gut microbiome composition, bacterial diversity, or abundance of specific species. Seventy-eight medications (41.9%) exhibited carryover effects detectable more than one year after last use. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, beta-blockers, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, proton pump inhibitors, and biguanides left enduring effects.

Limitations

The study used prescription data rather than direct observation of medication consumption, so researchers assumed people took medications they purchased. Sample sizes for specific medications were limited, though adequate for broader drug classes. The cohort was predominantly Estonian and female (70.3%), which may limit generalizability. Transportation time between stool collection and freezing varied and was associated with beta diversity at the second time point.

Funding and Disclosures

The study was funded by Estonian Research Council grant PRG1414, EMBO Installation grant 3573, Biocodex Microbiota Foundation, and Estonian Center of Genomics/Roadmap II project 16-0125. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Publication Details: Aasmets O, Taba N, Krigul KL, Andreson R, Estonian Biobank Research Team, Org E. A hidden confounder for microbiome studies: medications used years before sample collection. mSystems. Published online September 5, 2025. doi:10.1128/msystems.00541-25