The smart response to a set of made-up rules is to tweak them before anyone knows you will break them. We do it with diets. Treasurers do it with budgets. I did it with books. About a year ago, I was nearing certain failure in my attempt to read my way around the world. I was supposed to be on the latest leg of a journey that began during the travel bans of the pandemic, when I aimed to read 52 books from 52 countries in 52 weeks.

My daughter set me the challenge, and it was almost effortless in the first two years, when I escaped Australia with every turn of a title page, and wrote about it here. By the end of 2024, I was stuck. Sometimes it took me weeks to get through a book. Then it took me forever to choose the next one. That’s why this column is about reading 52 books from 52 countries in 52 fortnights.

If this was reality television, I would have been voted off the island. Luckily, this challenge had no jury and only one judge. So I bent the rules. It wasn’t that all the books were bad. It’s just that I was slow, like an exhausted traveller missing a flight.

Exploring New Worlds Through Pages

I loved my time in Tokyo with a strange narrator in Convenience Store Woman, by Sayaka Murata. And in colonial Malaysia during a visit by Somerset Maugham in The House of Doors, by Tan Twan Eng. I was immersed in Santo Domingo and New Jersey in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by Junot Díaz. I was moved by the tale of a young boy in Libya thanks to Hisham Matar and his novel, In The Country of Men.

The thing about the arbitrary list, however, is that I could land in a place I was desperate to leave. I regretted stopping in North Korea to read about Kim Jong-un and his family in The Sister, by Sung-Yoon Lee. This took an academic approach to what should be an engrossing story of dynastic politics and totalitarian cruelty.

“Thank goodness for great writers such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Her collection, The Thing Around Your Neck, landed me in short stories from Nigeria, but many will know her as a powerhouse who roams across national borders.”

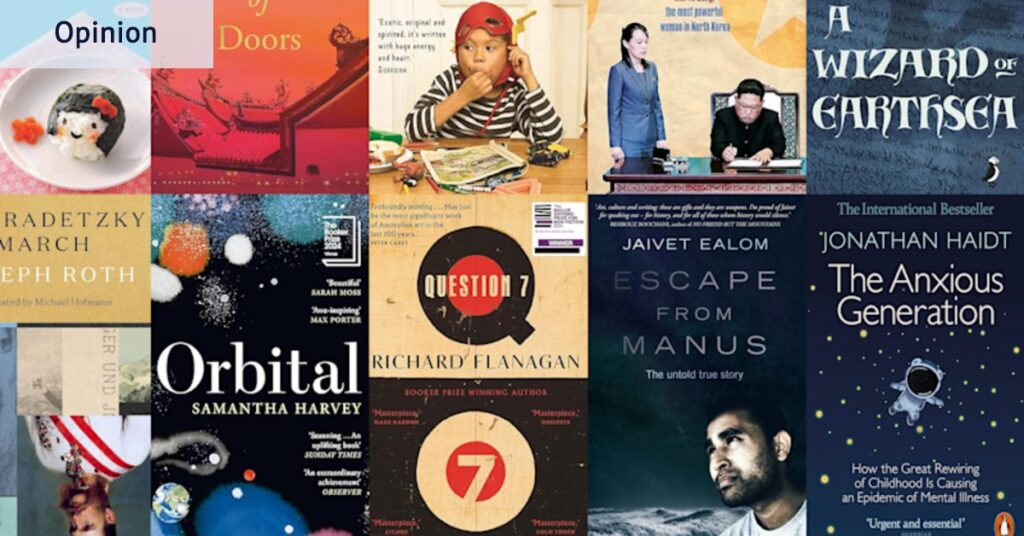

I experimented with stories from worlds that were invented or no longer existed. One was The Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula Le Guin. The other was The Radetzky March, by Joseph Roth, set during the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Challenging Comfort Zones

Returning to Australia, at least for a short while, I was glad I chose Question 7, by Richard Flanagan, a meditative memoir. Another book was impossible to label with a single country: Escape From Manus, by Jaivet Ealom, a Rohingya refugee, moved rapidly from Myanmar to Papua New Guinea and beyond. He assumed a false identity to escape, and it is a fascinating tale.

I know the target of 52 books can seem unserious, almost like a contest we should grow out of after school. In fact, it has two great qualities. First, it makes movement essential: you change landscapes and characters with each new title. Second, it forces risk: there can be a sameness to the stories from your own country, and there is a lot to be said for leaping out of your comfort zone.

There was not much comfort in my visit to Albania in Broken April, by Ismael Kadare, a bleak novel of a blood feud. Nor in the killing fields of Cambodia, in Surviving Year Zero, by Savonnora Ieng, a clear account of an ugly history. And not in Some People Need Killing, by journalist Patricia Evangelista, about political murder in the Philippines.

Discoveries and Reflections

I had time for only a single title from the US, something of a travesty, but at least I chose well: The Anxious Generation, by Jonathan Haidt, is an essential analysis of children and mental health in the iPhone era. I was engrossed in Caledonian Road, by Scottish author Andrew O’Hagan, who brought the modern class structure alive in a big story that ranged across elite and squalid London.

Then I was off to the valleys of Wales in The Life of Rebecca Jones, by Angharad Price. This short novel was a wonderful discovery for the way it evoked village life over generations. Soon afterwards I was in Ireland (and elsewhere) in Barcelona, a brilliant collection of short stories by Mary Costello.

“The more I read, the more sceptical I became about prizes for global fiction. I’ve had mixed success with the recent winners of The International Booker Prize, but I’ve loved some that did not even make the shortlist.”

What stood out were the books that offered insight into the world as it is. One of the best books of these 52 fortnights also missed out on the Booker. This was Lullaby, by Leila Slimani – an unsettling and absorbing account of a Moroccan nanny in Paris. It should have won in 2023.

One was The Death of a Soldier Told by His Sister, by Olesya Khromeychuk, a story of the war in Ukraine, and a family from Lviv, that avoided false heroics. Another was Necropolis, by Boris Pahor, a Slovenian writer who took me into parts of the Holocaust I had not known. When the year ended with the horror of the Bondi attack, it seemed to me even more necessary to read and remember the accounts that show where hatred leads.

Concluding Thoughts

Without a target, I might not have read Born A Crime, by Trevor Noah, who used to host The Daily Show. His memoir of growing up in South Africa is funny and thoughtful, which is why it has sold by the millions. The star of the tale is his mother, who made him go to church three times on Sundays.

Without a deadline, I would not have picked up a very, very short book to race through Denmark. This was The Emperor’s New Clothes, by Hans Christian Andersen, a tale we all know but can all read again. It skewers political vanity with a smile – and we all know the modern ruler who wears the same old fashion.

The best of the books? Looking back, I think of Homegoing, by Ghanaian-American writer Yaa Gyasi, as the perfect reason to read fiction. It took me somewhere I had never been, it brought characters alive, and it did this with light but perceptive prose. It’s the kind of book you give to friends in the hope they will love it, too.

Thank you for reading and subscribing. I wish you the best for the year ahead. We cannot be sure where the world is heading, so it might help to get lost in a good book.

“52 books from 52 countries in 52 fortnights”

- Nathacha Appanah, The Last Brother, Mauritius, 2007

- Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Nomad, Somalia / Holland / USA, 2010

- Joseph Roth, The Radetzky March, Austro-Hungarian Empire, 1932

- Ursula le Guin, The Wizard of Earthsea, US / Earthsea, 1968

- Hila Blum, How to Love Your Daughter, Israel, 2023

- Margaret Atwood, Surfacing, Canada, 1972

- Sallust, The Conspiracy of Cataline, Rome, 40BC

- Jaivet Ealom, Escape From Manus, Myanmar / Australia / PNG / Canada, 2021

- Patricia Evangelista, Some People Need Killing, The Philippines, 2023.

- Murong Xuecon, Deadly Quiet City, China, 2022

- Faysal Khartash, Roundabout of Death, Syria, 2017

- Leo Vardiashvili, Hard By A Great Forest, Georgia, 2023

- Eleanor Catton, Burnam Wood, New Zealand, 2023

- Olga Tokarczuk, Flights, Poland, 2007

- Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation, USA, 2024

- Ramita Navai, City of Lies, Iran, 2014

- Kapka Kassabova, Border, Bulgaria, 2017

- Ia Genberg, The Details, Sweden, 2022

- Anna Funder, Wifedom, Australia, 2023

- Soname Yangchen, Child of Tibet, Tibet / UK, 2006

- Junot Diaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Santo Domingo, 2007

- Hisham Matar, In The Country of Men, Libya, 2006

- Nilima Rao, A Disappearance in Fiji, Australia / Fiji, 2023

- Savannora Ieng, Surviving Year Zero, Cambodia, 2014

- Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing, Ghana, 2016

- Tan Twan Eng, The House of Doors, Malaysia, 2023

- Leila Slimani, Lullaby, Morocco / France, 2018

- Sung-Yoon Lee, The Sister, North Korea, 2023

- Andrew O’Hagan, Caledonian Road, UK, 2024

- Jenny Erpenbeck, Kairos, Germany, 2023

- Willem Frederik Hermans, An Untouched House, The Netherlands, 1951

- Thomas Bernhard, The Rest Is Slander, Austria, 2022

- Angharad Price, The Life of Rebecca Jones, Wales, 2002

- Veronica Raimo, Lost On Me, Italy, 2022

- Hans Christian Andersen, The Emperor’s New Clothes, Denmark, 1837

- Fred Charles Ikle, Every War Must End, Switzerland / US, 1971

- Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes From Underground, Russia, 1864

- Oliver Lovrenski, Back In The Day, Norway, 2023

- Ismael Kadare, Broken April, Albania, 1978

- Georges Simenon, The Man From London, Belgium, 1934

- Mary Costello, Barcelona, Ireland, 2024

- Milan Kundera, 89 Words and Prague, A Disappearing Poem, Czechia, 2025

- Richard Flanagan, Question 7, Australia, 2023

- Sayaka Murata, Convenience Store Woman, Japan, 2016

- Samantha Harvey, Orbital, UK and Low Earth Orbit, 2023

- Olga Ravn, The Employees, Denmark, 2018

Note: The list has 56 books, which reflects my indecision at times. It has two from Australia: Question 7, by Richard Flanagan, and Wifedom, by Anna Funder. It has two authors from Denmark: Hans Christian Andersen, but also Olga Ravn. This was because counting The Emperor’s New Clothes as a book felt like cheating. There are two from the US, also, because Fred Charles Ikle was born in Switzerland but spent most of his life in the US. I include his book, Every War Must End, because it is so good.

David Crowe is Europe correspondent for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.