Caleb Pitt-Cook, a 24-year-old Ngarluma man, drifts just above the ocean floor, his fingers sifting through the soft sand in search of ancient stone tools used by his ancestors thousands of years ago. “If you told me I’d be doing this work two years ago, I would have laughed in your face,” he admits. “It’s one of the coolest parts of our job. I’d say it’s my favourite part right now.”

Pitt-Cook is a ranger with the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation, contributing to groundbreaking research that has already made history. “There’s only ever been two submerged Aboriginal archaeological sites mapped in Australia,” notes Flinders University maritime archaeologist John McCarthy. “Those were found by our team here.”

Uncovering Submerged History

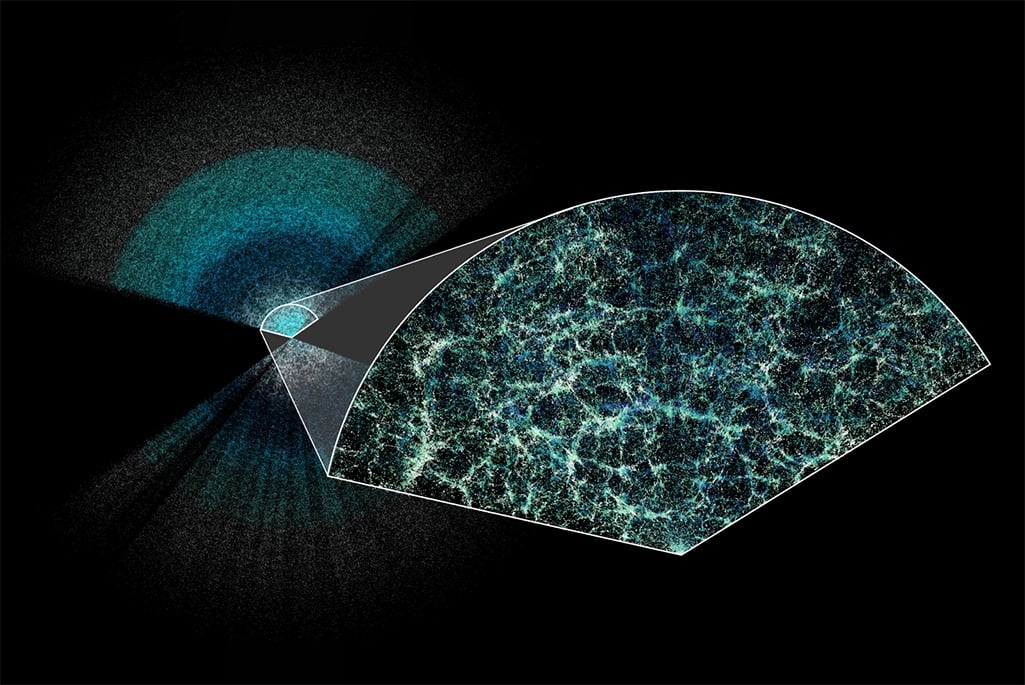

When humans first populated the Australian continent about 65,000 years ago, the sea level was significantly lower. “There’s a huge area of archaeological landscape that’s been lost to sea level change,” explains Dr. McCarthy. “Back then, you could have walked all the way to Indonesia.”

Since 2019, Dr. McCarthy’s team has been searching for artefacts from that era, submerged off the coast of the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia, known to its traditional custodians as Murujuga. “The initial discoveries made in Murujuga were stone tools. They’re very common — the sort of knives and forks of their day,” Dr. McCarthy says. “They survive very well through sea-level change because they’re made of igneous rock, which is very hard and durable.”

Rangers Find Purpose Underwater

This year’s underwater surveys mark the first time Indigenous rangers have joined maritime archaeologists in Australia. This collaboration is the result of over a year of training for several Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation rangers. Ngarluma ranger Malik Churnside describes the experience: “First, you start off with pool dives, and it’s a big jump up to actually get out on the water. Once you’re out there in the water and there’s actually animals … sharks swimming around, it can be quite a scary sight, at first.”

One of the submerged sites Churnside surveyed was once a freshwater spring, referenced in a Ngarluma cultural song still sung by elders today. “It’s just like evidence and a connection to something they’ve talked about and sung about for such a long time,” he says. “It’s purpose and meaning; you get a sense of belonging to this whole landscape and the people that were here before.”

Technology Bridging Past and Present

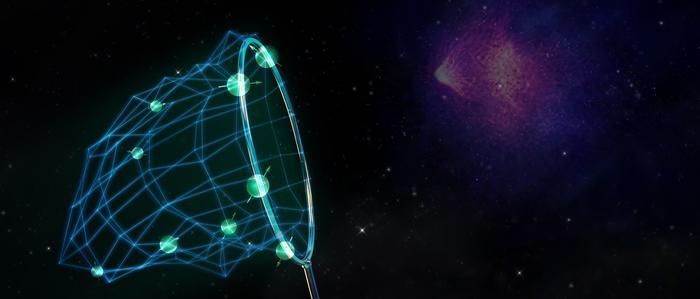

Back at camp, Yindjibarndi man and Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation director Vincent Adams dons a virtual reality headset, transporting him from the hot Pilbara afternoon to the silty depths of Murujuga. The headset connects to a live feed from a remote-operated vehicle (ROV), allowing elders to identify artefacts in real time. “It’s like 20 years ago when the mobile phone came out and they were all frightened of it,” Adams laughs. “This headset? They were frightened of it … [then] you couldn’t get them off it.”

Adams notes that several artefacts trace back to ancient hunting, crafts, and ceremonies, practices that persist today. “When they bring this up from under water, we can see that this is history from here, culture from here,” he says. This technology also offers an opportunity to inform researchers about the local lore and rules behind the tools. “If it’s men’s stuff [that] comes up, women can’t see this, kids can’t see it. Only men that have been through law,” Adams explains.

Implications for Cultural Heritage and Industry

The ROV enables the team to survey larger, more challenging areas rapidly. Mapping these sites is crucial for cultural heritage protections, especially in waters frequented by bulk carriers and offshore pipelines. Murujuga intersects with the Carnarvon basin, home to Australia’s largest gas reserves. Geoff Bailey, a world authority on submerged landscapes, emphasizes the importance of robust information for industry navigation. “If somebody puts a hole in the seabed … they’re quite likely to expose something that is of relevance and interest to the environmental history of the landscape and the cultural history of that landscape,” he says. “The key to this is good communication and understanding.”

Earlier this month, the Murujuga Cultural Landscape was granted World Heritage status by the United Nations in recognition of its outstanding universal value. UNESCO’s unanimous ruling highlighted the underwater archaeological work as a critical component of the nomination and called for further study.

Vincent Adams underscores the research’s importance as more gas projects emerge. “This has popped up a lot of times in conversations with elders, saying what about the pipeline?” he says. “There’s no law, there’s no rule for any of this. We’re paving the way for this to happen.”

For Caleb Pitt-Cook, the underwater exploration is a time of reflection. “Our culture is an oral-based tradition so it’s all passed down through generations of speaking, songs, and teaching,” he explains. “A lot of people are really sceptical because we don’t have anything written down on paper. But to actually go out and explore these places where the stories originate from is really special. It’s a whole different world under the water.”