In a comprehensive study leveraging Sweden’s extensive population registers, researchers have uncovered a complex relationship between genetic predisposition and the onset of alcohol use disorder (AUD) in women during pregnancy and early motherhood. The study, conducted by a team based in Lund, Sweden, analyzed data from nearly 1.8 million women born between 1960 and 1995, focusing on those who experienced their first onset of AUD between the ages of 15 and 40.

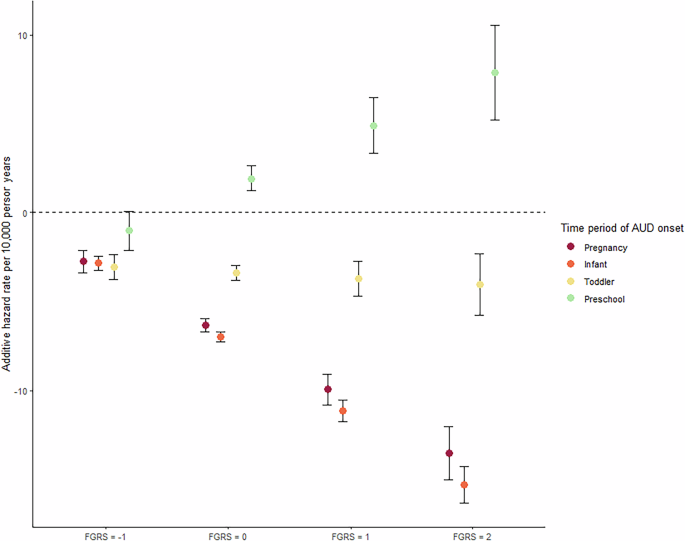

The research, which received ethical approval from the regional ethical review board in Lund, examined how genetic liability, measured by a family genetic risk score (FGRS), interacts with various maternal stages—pregnancy, infancy, toddlerhood, and preschool years—to influence AUD risk. The findings suggest that these maternal stages can have both protective and predisposing effects on AUD risk, depending on the level of genetic liability.

Understanding the Genetic Risk

The study utilized the family genetic risk score (FGRS) to estimate an individual’s genetic liability to AUD. This score is derived from the morbidity risks in relatives, offering insights into how genetic predispositions might influence AUD onset. The FGRS was scaled within the total cohort of men and women, ensuring a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, facilitating comparisons across the population.

Crucially, the study revealed that women with higher FGRS are more susceptible to developing AUD at a younger age and are more likely to experience their first pregnancy earlier. This genetic predisposition was found to interact significantly with the maternal stages, altering the risk of AUD onset.

Maternal Stages and AUD Risk

The research identified four key maternal stages: pregnancy, infancy (child aged 0–12 months), toddlerhood (13–36 months), and preschool years (37–60 months). Each stage was analyzed for its impact on AUD risk, revealing nuanced interactions with genetic liability.

“The protective effect of being pregnant or having an infant is stronger in individuals with high genetic risk for AUD,” the study noted, highlighting a significant interaction between genetic predisposition and maternal status.

Interestingly, the study found that being pregnant or caring for an infant generally reduced the risk of AUD onset, with the protective effect intensifying in those with higher genetic risk. Conversely, having a preschooler was associated with an increased risk of AUD, particularly in mothers with high genetic liability.

Age and Maternal Status: A Dynamic Relationship

The study further explored how these relationships varied with maternal age, dividing participants into five age groups: 15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, and 35–39. The findings indicated that younger mothers, particularly those aged 20–24, were more sensitive to the AUD predisposing effects of having a preschooler, while older mothers exhibited more muted effects across all maternal stages.

For teenage mothers, the protective effects of pregnancy and infancy were only marginally present, whereas the risk associated with having a toddler increased significantly with rising genetic risk. This dynamic shifted in older age groups, where the protective effects of having a toddler became more pronounced, especially in those at high genetic risk.

Implications and Future Directions

The study’s findings have significant implications for public health strategies and interventions aimed at reducing AUD risk in new mothers. The protective effects of pregnancy and infancy, particularly in those with high genetic risk, underscore the potential for targeted interventions during these stages. Moreover, the increased risk associated with preschool years highlights the need for continued support and screening for alcohol problems in mothers with young children.

“Routine screening for alcohol problems in women with toddlers and preschoolers is crucial, especially if they are young and have a positive family history for AUD,” the researchers emphasized.

While the study provides valuable insights, it also acknowledges several limitations, including the reliance on registry data and the exclusion of paternal influences. Future research could expand on these findings by incorporating a broader range of covariates and exploring the role of fathers in AUD risk.

Overall, this study contributes to a growing body of literature on gene-environment interactions in psychiatric and substance use disorders, offering new perspectives on the complex interplay between genetic risk and maternal status in shaping AUD outcomes.