There’s a persistent saying within the type 1 diabetes community that a cure has been “just five years away” for as long as anyone can remember. Despite decades of promises and research, the elusive cure remains out of reach. But is there truly a cure for type 1 diabetes? The short answer is no. Even if a groundbreaking discovery were made tomorrow, it would likely take much longer than five years to become widely available.

However, there are reasons to remain hopeful. While a single, miraculous solution seems improbable, researchers have made significant strides in developing therapies that could one day liberate many patients from the need for insulin.

Understanding What a ‘Cure’ Means for Type 1 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the insulin-producing islet cells in the pancreas. For most, a cure would mean restoring the body’s ability to produce its own insulin, maintaining normal blood sugar levels without insulin injections or ongoing management.

Camillo Ricordi, MD, director emeritus of the Diabetes Research Institute in Miami, emphasizes that a true cure must restore normal blood sugar levels “without antirejection drugs or any toxic interventions that may introduce other problems.” He asserts, “You cannot replace diabetes with another disease.”

Over the past two decades, significant progress has been made toward therapies that could restore insulin independence, even if they do not reverse the underlying autoimmunity. These therapies often involve pancreas and stem cell transplants, which still require immunosuppressive drug regimens, raising questions about their status as true cures.

Pancreas Transplants: A Complex Solution

Some individuals who undergo pancreas transplants no longer need insulin or blood sugar monitoring, effectively putting their type 1 diabetes into remission. However, this option is not practical for most patients due to several factors:

- The necessity of lifelong antirejection drugs

- Only about half of recipients achieve true insulin independence

- The surgery is intense, costly, and risky

- Donor pancreases are scarce

Consequently, pancreas transplants are typically reserved for those receiving kidney transplants due to end-stage diabetic kidney disease or individuals facing severe management challenges.

Islet Cell Transplants: A Less Invasive Approach

Islet cell transplants involve transplanting only the insulin-producing cells, rather than the entire pancreas. This less invasive procedure has shown promising results, with some recipients enjoying insulin-free blood sugar control for over a decade. However, challenges persist:

- Antirejection medication is still required

- Some recipients need multiple infusions

- The procedure was only recently approved in the U.S.

- Limited availability due to donor pancreas scarcity

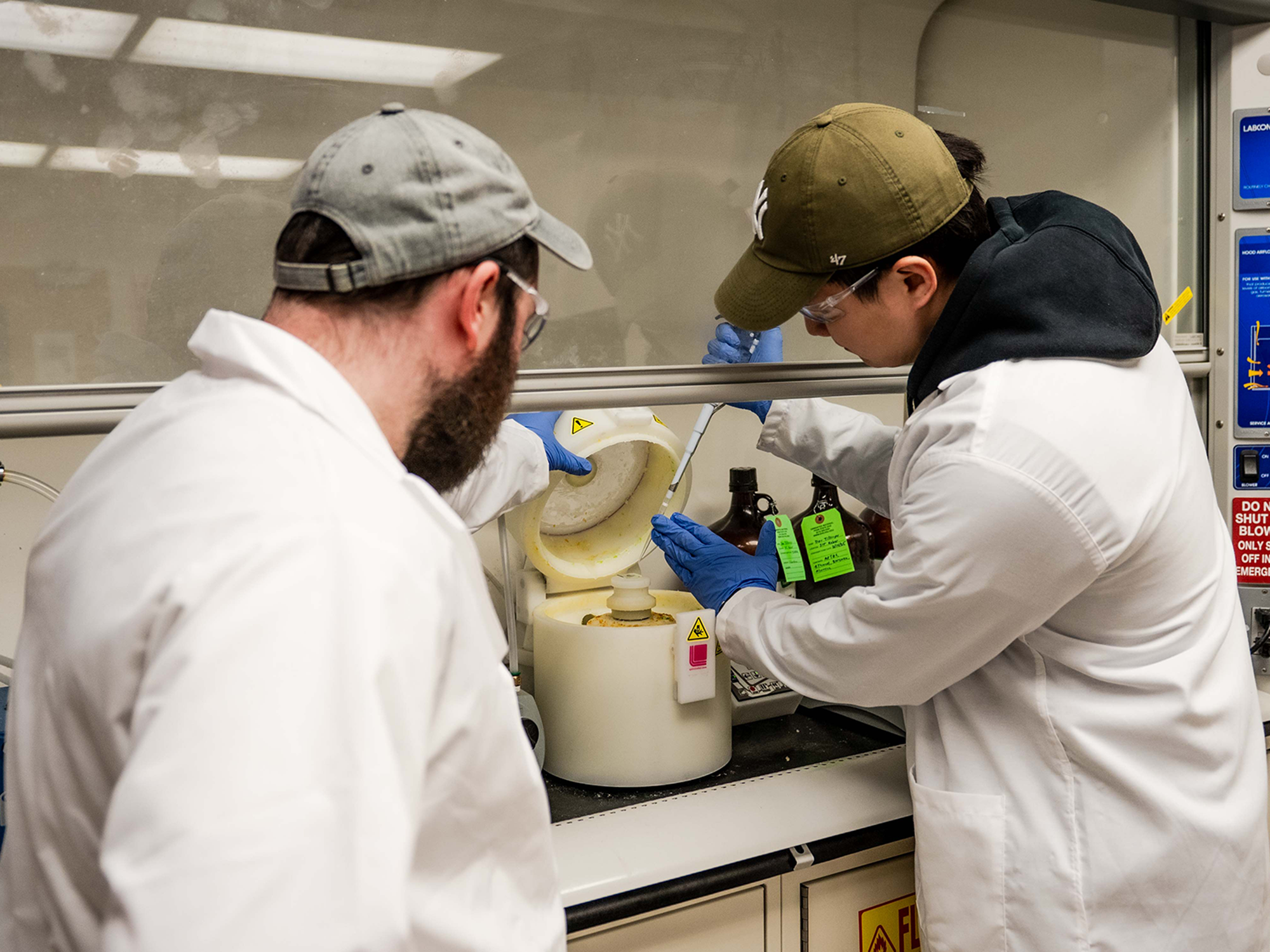

Lab-Grown Islet Cells: A Promising Future

To address the shortage of donor organs, researchers have developed a method to grow human islet cells in a laboratory using stem cells, potentially providing an unlimited supply for transplantation. Although still in experimental trials, the results have been encouraging. A new therapy, zimislecel, has shown that ten out of twelve volunteers achieved full insulin independence after one year.

This experimental therapy could be the closest to a practical cure, but it must undergo extensive stage 3 testing to assess safety and efficacy. Even if successful, its availability remains uncertain.

The Challenge of Immunosuppression

Dr. Ricordi highlights the importance of developing a therapy that eliminates the need for antirejection drugs, which can cause significant side effects and health risks. “The ultimate goal is to do these transplants without immunosuppression,” he states.

Current research is focused on protecting or hiding islet cells from the immune system, exploring various innovative approaches:

- Gene-editing techniques to conceal islet cells

- Physical barriers to encapsulate cells

- Immunosuppressive microgels mixed with islet cells

- Nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery

While some technologies are still in early development, others have faced setbacks, such as a recently discontinued physical pouch designed to shield lab-grown islet cells.

Alternative Paths: Islet Cell Regeneration

Beyond transplantation, researchers are exploring therapies to regenerate the body’s natural insulin production. This involves activating progenitor cells or encouraging beta cell duplication. However, these therapies would still require a method to prevent autoimmune attacks on newly created beta cells.

Dr. Ricordi advocates for a multifaceted approach, stating, “I believe in a combination strategy. I’m not sure there will ever be a silver bullet that will be 100 percent successful for everybody.”

Timeline and Financial Implications

Dr. Ricordi, a veteran in diabetes research, believes we may be only years away from experimental proof of a real cure. Yet, even in the best-case scenario, it could take many more years to make such a cure widely available. He warns, “It will take five years to follow up on the initial group,” and scaling up production could be a lengthy process.

Furthermore, the cost of advanced cell therapies could be prohibitive, potentially limiting access to a small subset of patients. “Advanced cell therapies can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars,” Ricordi notes.

While progress is promising, it’s crucial not to create false hope. The journey to a cure is ongoing, and the condition remains easier to manage than ever before.

Automated Insulin Delivery Systems: A Technological Aid

Though not a cure, automated insulin delivery (AID) systems offer significant improvements in diabetes management. These systems combine continuous glucose monitors with insulin pumps, using algorithms to adjust insulin delivery automatically. While they enhance quality of life, they still require manual insulin dosing for meals and sugar intake to counter hypoglycemia.

Future advancements may lead to AID systems that operate so efficiently that patients can temporarily forget about their diabetes. However, these systems remain a management tool rather than a cure.

In conclusion, while a cure for type 1 diabetes remains elusive, ongoing research and technological advancements offer hope for improved management and potential future breakthroughs.