A groundbreaking study from Bar-Ilan University has unveiled that one of sleep’s core functions originated hundreds of millions of years ago in jellyfish and sea anemones, some of the earliest creatures with nervous systems. This research traces the mechanism back to these ancient animals, demonstrating that protecting neurons from DNA damage and cellular stress is a fundamental, ancient function of sleep that predates the evolution of complex brains.

Although sleep is universal among animals with nervous systems, it poses significant survival risks: during sleep, awareness of the environment diminishes, leaving animals more vulnerable to predators and interrupting essential behaviors such as feeding and reproduction. The persistence of sleep across evolutionary history has long puzzled biologists. According to this study, sleep’s indispensable function emerged early in animal evolution and is so crucial that it outweighed its inherent dangers.

Tracing Sleep’s Ancient Roots

The study was jointly led by Prof. Lior Appelbaum’s and Prof. Oren Levy’s laboratories at Bar-Ilan University. Previous research by the Appelbaum Lab showed in zebrafish that neurons accumulate DNA damage during wakefulness and require sleep to recover, underscoring the need to reduce DNA damage as a fundamental driver of sleep. DNA damage can arise from various sources, including neuronal activity, oxidative stress, metabolism, and radiation. While DNA damage can be detrimental to all cells, neurons require sleep to avoid genome insults, possibly because they are unique non-dividing excitable cells.

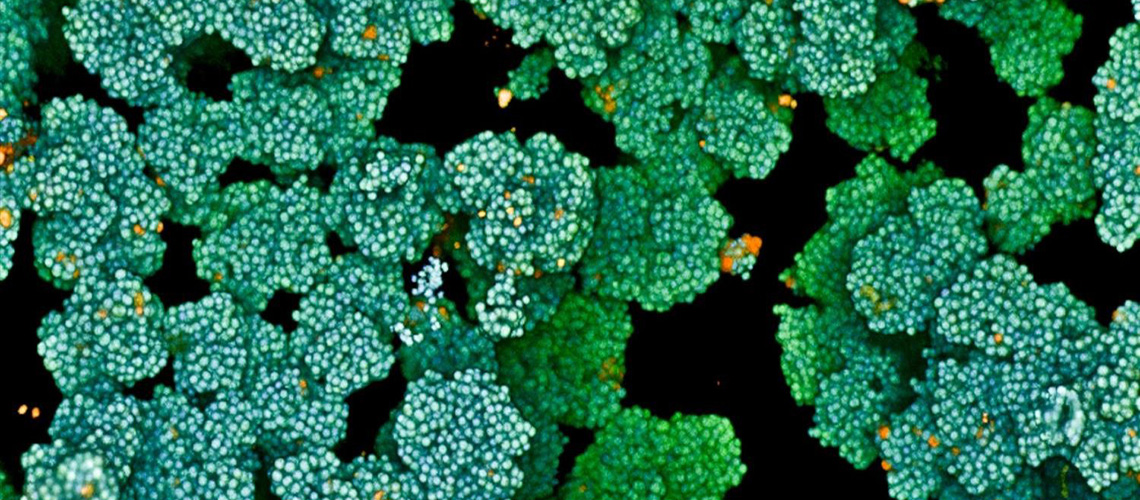

In the current study, published in Nature Communications, Dr. Raphael Aguillon, Dr. Amir Harduf, and colleagues from the Appelbaum and Levy labs defined and characterized sleep patterns in two ancient animal lineages: diurnal, symbiotic jellyfish that sleep at night and nap briefly at mid-day, and crepuscular, non-symbiotic sea anemones that sleep from dawn through the first half of the day. Using infrared video tracking and behavioral analysis, they observed that both creatures sleep roughly eight hours daily, similar in duration to human sleep.

Mechanisms of Sleep Regulation

Despite their different lifestyles and mechanisms controlling sleep, jellyfish and sea anemones share a common pattern: DNA damage accumulates in neurons during wakefulness and is reduced during sleep. When the animals were kept awake and DNA damage increased, they slept longer afterward. This behavior, known as sleep rebound, enabled recovery and reduction of DNA damage levels.

The study also showed that increasing DNA damage, either through UV radiation or exposure to a DNA-damaging chemical, triggered recovery sleep in both species. Conversely, promoting sleep with the hormone melatonin reduced DNA damage. These findings reveal a bidirectional relationship in which DNA damage increases sleep need, and sleep, in turn, facilitates damage reduction, suggesting that protecting neurons from daily cellular stress and DNA damage may have been the evolutionary driver of sleep.

Implications for Human Health

The two basal animals also reveal how sleep is regulated differently. While homeostatic sleep pressure regulates sleep in both species, sleep is mainly controlled by the light-dark cycle in the jellyfish. In contrast, the sea anemone relies mostly on its internal circadian clock. However, despite these differences, both animals depend on sleep to reduce DNA damage and cellular stress, whether their sleep/wake cycle is driven by sunlight or internal timing.

“Our findings suggest that the capacity of sleep to reduce neuronal DNA damage is an ancestral trait already present in one of the simplest animals with nervous systems,” said Prof. Lior Appelbaum, principal investigator of the Molecular Neuroscience Lab at the Faculty of Life Sciences and Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center at Bar-Ilan University. “Sleep may have originally evolved to provide a consolidated period for neural maintenance, a function so fundamental that it may have been preserved across the entire animal kingdom.”

The study also has important implications for human health. Sleep disturbances in humans are associated with cognitive decline and an increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, which may involve chronic accumulation of neuronal DNA damage. The evolutionary evidence provided by this research strengthens the link between sleep quality and long-term brain resilience.

“Sleep is important not just for learning and memory, but also for keeping our neurons healthy. The evolutionary drive to maintain neurons that we see in jellyfish and sea anemones is perhaps one of the reasons why sleep is essential for humans today,” concluded Prof. Appelbaum.

This development follows a growing body of research emphasizing the critical role of sleep in maintaining neurological health. As scientists continue to unravel the mysteries of sleep, these insights could lead to improved treatments for sleep disorders and neurodegenerative diseases, highlighting the profound impact of evolutionary biology on modern medicine.