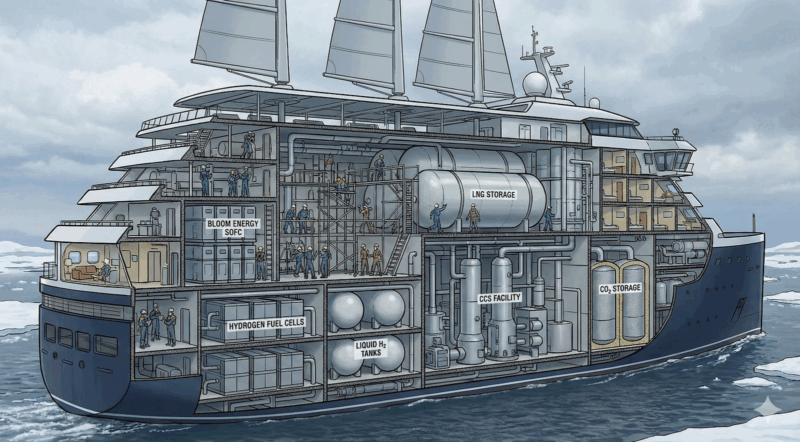

The maritime industry is at a crossroads, confronted with the challenge of balancing innovative propulsion technologies with practical needs. A recent concept cruise vessel by Ponant, GTT, and Bloom Energy proposes a combination of hard wing sails, LNG-fed Bloom solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs), hydrogen fuel cells, and onboard carbon capture. While ambitious, this configuration raises questions about its feasibility and alignment with the maritime sector’s practical requirements.

Maritime propulsion is a complex issue due to the unique demands placed on ships, which must operate continuously and reliably across vast distances under varying conditions. The proposed vessel’s reliance on multiple novel technologies prompts a critical examination of what the maritime sector truly needs, what shipyards can construct, and what ports can support.

Challenges of Complex Maritime Technologies

The introduction of Bloom Energy’s SOFCs into maritime applications has sparked debate. These cells, which run on natural gas or biogas, are touted for their high efficiency. However, they present significant challenges when adapted for maritime use. The modules are bulky and operate at high temperatures, necessitating extensive insulation and thermal management. This creates engineering challenges in confined ship machinery spaces.

Moreover, the SOFC modules degrade rapidly, with a median replacement cycle of around five years. In stationary applications, modules can be swapped with cranes, but on ships, this would require significant structural modifications, such as large openings in decks for heavy lifts—an approach not currently feasible in standard ship design.

“A ship with a 10 MW requirement might need thirty or more Bloom modules arranged in banks, with substantial spacing and significant cooling and ventilation. The result is a machinery volume several times larger than a traditional dual fuel engine installation.”

Comparing Fuel Options: LNG, Methanol, and Hydrogen

When evaluating energy density and efficiency, LNG-fed SOFCs fall short compared to traditional marine engines. While LNG is less energy-dense than VLSFO, the process of converting it to hydrogen for use in SOFCs results in significant energy loss. In contrast, methanol engines utilize both hydrogen and carbon energy without discarding a substantial portion of the fuel’s potential.

Hydrogen fuel cells, another component of the proposed vessel, introduce further complications. Hydrogen’s low volumetric energy density requires large storage solutions, which impose penalties on naval architecture. The integration of hydrogen systems alongside LNG increases the complexity and safety requirements, stretching the capabilities of current maritime operations.

“Marine hydrogen systems must meet strict safety rules including double wall piping, specialized sensors, and large exclusion zones.”

Onboard Carbon Capture: A Complex Addition

The inclusion of carbon capture systems adds another layer of complexity. While Bloom’s SOFCs produce a relatively concentrated CO2 exhaust, the process of converting this to a high-purity CO2 stream involves substantial equipment and energy consumption. The storage and handling of liquid CO2 present logistical challenges, as few ports are equipped to manage these operations.

Each of these technologies, when combined, multiplies the risk and complexity of the vessel’s operation. The need for specialized knowledge and training for crew members further complicates the integration of these systems into the maritime industry.

A Practical Path Forward: Methanol and Battery Hybrid Systems

In contrast to the multi-technology approach, hybrid biomethanol and battery systems offer a more practical solution for maritime decarbonization. Methanol engines are already commercially available and are being installed on various vessel types. Methanol’s liquid state at ambient temperatures allows for straightforward storage and handling, fitting well within existing maritime practices.

Batteries complement methanol engines by providing peak shaving, hotel load support, and zero-emission operation in ports. They can be easily integrated into ship designs, offering a scalable and maintainable solution that aligns with current maritime engineering training.

“Shipping tends to adopt technologies that lower operational risk and simplify compliance. The solutions that succeed will be those that deliver reliability and practicality first and emissions reductions as a consequence.”

Conclusion: Navigating the Future of Maritime Propulsion

The maritime industry must prioritize solutions that are buildable, maintainable, and scalable. While the concept vessel proposed by Ponant, GTT, and Bloom Energy is innovative, it does not align with the practical needs of the sector. The complexity and risks associated with integrating multiple novel technologies make it an unlikely candidate for widespread adoption.

Hybrid biomethanol and battery systems, on the other hand, offer a viable path forward. They integrate seamlessly with existing maritime infrastructure and provide a practical approach to reducing emissions. As the industry navigates the challenges of decarbonization, these solutions represent a balanced approach that respects the operational realities of shipping.