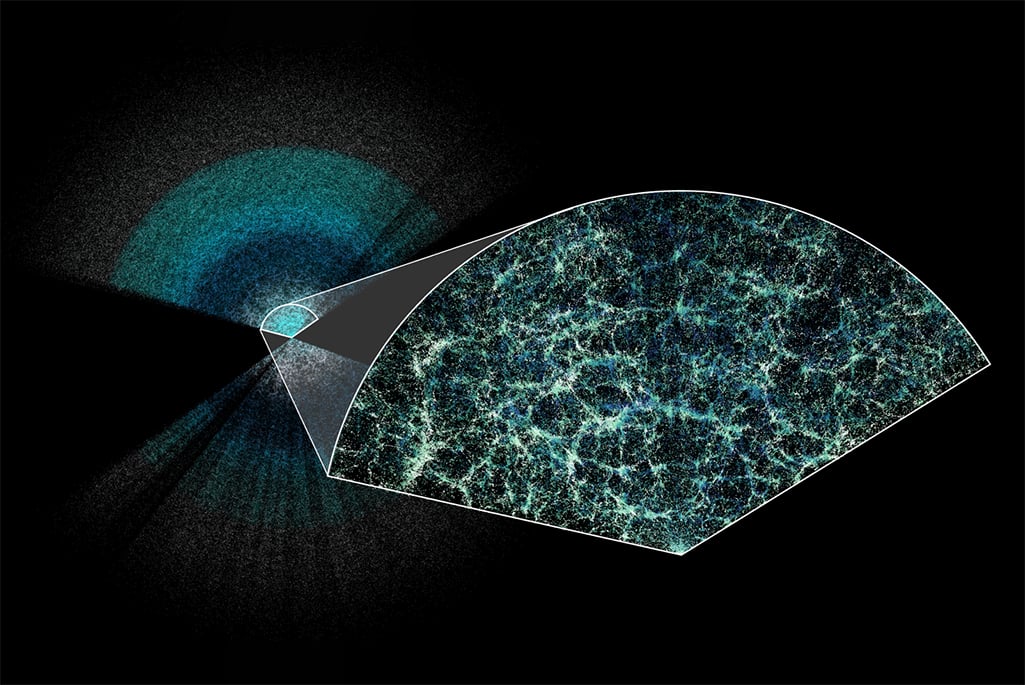

LONDON — Imagine all of Earth’s oceans, which cover approximately 70% of the planet and are predominantly composed of hydrogen. Now, multiply that volume by nine. This is the estimated amount of hydrogen that might be contained within Earth’s core, potentially making it the planet’s largest hydrogen reservoir, according to recent research.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, suggests that the core could hold between nine to 45 oceans’ worth of hydrogen. This translates to hydrogen comprising roughly 0.36% to 0.7% of Earth’s total core weight. The findings challenge previous theories that Earth acquired most of its water through comet impacts, proposing instead that the planet’s water was acquired as it formed. Lead author Dongyang Huang, an assistant professor at Peking University, emphasized, “Earth’s core would store most of the water in the first million years of Earth’s history.”

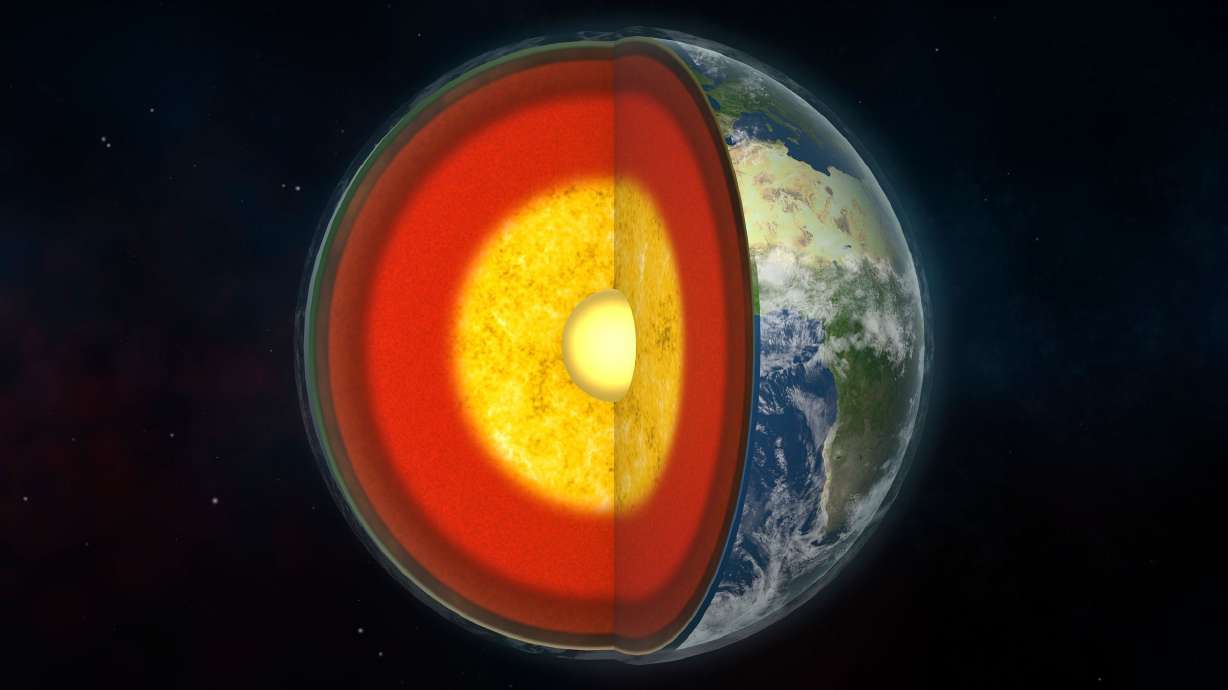

Formation of Earth’s Core

More than 4.6 billion years ago, the young Earth was formed from the collision of rocks, gas, and dust surrounding the sun. These collisions gradually shaped the planet’s core, mantle, and crust. Deep within Earth’s interior, under immense pressure, a dense, hot, and fluid metal core began to form. Composed mainly of iron and nickel, this core is responsible for generating Earth’s protective magnetic field.

Rajdeep Dasgupta, a professor at Rice University who was not involved in the study, noted, “Hydrogen can only enter the core-forming metallic liquid if it was available during Earth’s main growth phases and participated in core formation.”

Challenges in Measuring Hydrogen

Understanding the origin and distribution of hydrogen is crucial for comprehending planetary formation and the evolution of life on Earth. However, measuring hydrogen in Earth’s core is challenging due to its depth and the extreme conditions that are difficult to replicate in laboratories. Moreover, hydrogen’s lightness and small size make it elusive to standard analytical methods.

“Hydrogen is difficult to quantify because it is the lightest and smallest element, meaning its quantification is beyond the capacities of routine analytical methods,” Huang explained.

Previous studies have inferred the amount of hydrogen in the core by examining the lattice structure of iron crystals, which expand when hydrogen is present. However, these estimates have varied widely, from 10 parts per million to 10,000 parts per million, equating to between 0.1 and over 120 oceans’ worth of hydrogen.

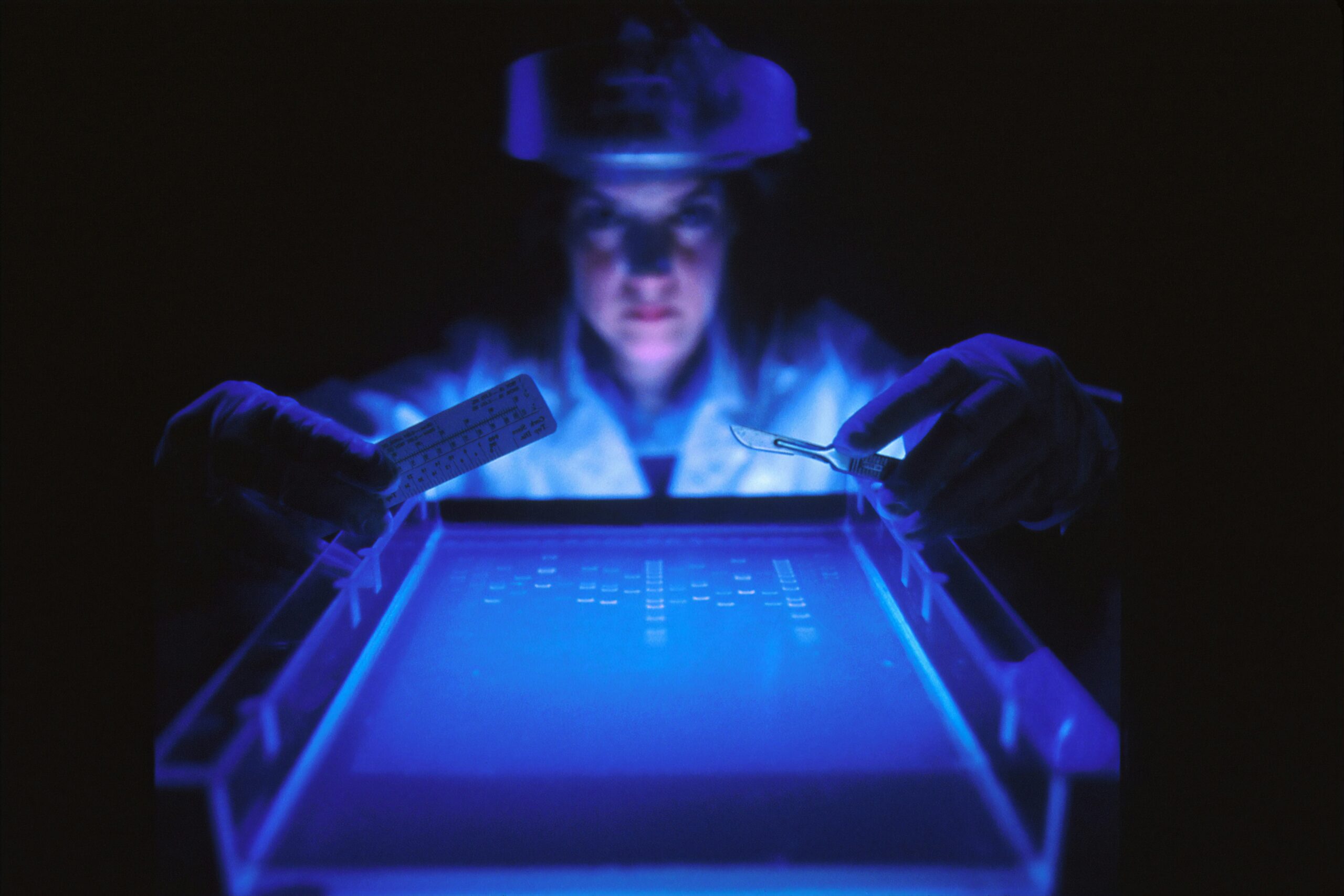

Innovative Techniques in Research

The recent study employed a novel approach to estimate the hydrogen content in Earth’s core. Researchers used atom probe tomography to observe hydrogen and other elements at the atomic scale. This technique involves shaping samples into needlelike forms and ionizing their atoms for individual counting.

By replicating core temperatures and pressures in a diamond anvil cell, scientists melted iron using lasers and directly observed the interactions between hydrogen, silicon, and oxygen. Their findings indicated a hydrogen-to-silicon ratio of approximately 1:1, allowing them to approximate the core’s hydrogen content.

Uncertainties and Future Research

While the study provides new insights, it also acknowledges uncertainties. The indirect nature of the research means that further work is needed to refine these estimates. Kei Hirose, a professor at the University of Tokyo, pointed out that the actual hydrogen content might be higher than reported, citing potential hydrogen loss during decompression.

“If the authors’ measurements and hypothesis hold true, it will suggest that hydrogen was delivered throughout Earth’s growth,” Dasgupta stated.

Hirose added that hydrogen could have originated from various sources, including gas from nebulas and water from comets and asteroids. This underscores hydrogen’s role as an essential element for life on Earth, alongside carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus.

Implications for Earth’s Evolution

The interplay between hydrogen, silicon, and oxygen in Earth’s core offers clues about the planet’s magnetic field development, which is crucial for making Earth habitable. As research continues, these findings will inform future discussions on planetary formation and the role of volatile elements in Earth’s history.

The study’s innovative techniques and findings represent a significant step forward in understanding Earth’s deep interior and its implications for the planet’s past and future.