Could slightly elevated blood sugar levels lead to serious health problems in the future? A single patient’s question has sparked nearly a decade of research, culminating in a groundbreaking model that could reshape how clinicians and researchers understand and manage diabetes across the United States.

While working as a fellow in the clinic, Dr. Neda Laiteerapong, Professor of Medicine and Chief of General Internal Medicine at the University of Chicago, encountered a patient who posed a deceptively simple question. The patient, an experienced nurse, had been living with elevated blood sugars for about three years without starting treatment. “Did I harm myself by waiting?” she asked.

At the time, Laiteerapong lacked a definitive answer. “I wanted to say, ‘Yes, absolutely,’ but I didn’t have any evidence to support that,” she recalls. This uncertainty set her on a mission to understand the impact of early treatment, the costs of delaying it, and the potential benefits over time.

The Development of the DOMUS Model

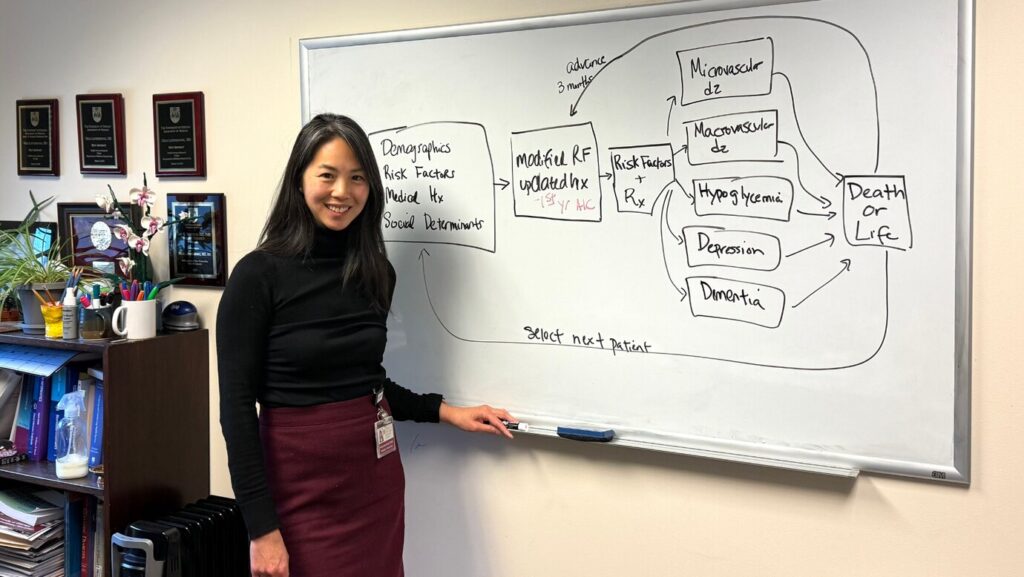

Using real-world patient data from Kaiser Permanente, Laiteerapong and her team developed the Multiethnic Type 2 Diabetes Outcomes Model for the U.S. (DOMUS). This model predicts not only traditional complications of diabetes, such as heart attacks and kidney failure, but also outcomes like depression and dementia, which have gained attention in recent years.

DOMUS, recently published in Diabetes Care, forecasts 14 different complications that patients with diabetes can develop over approximately 15 years. It models disease progression by predicting changes in weight, cholesterol, A1C levels, and other risk factors over time.

While other diabetes models exist, such as the UKPDS model based on 30 years of data from about 5,000 patients in the UK, DOMUS uses a significantly larger and more diverse dataset—129,000 patients over a 12-year period. This dataset tracks prescriptions, lab tests, follow-ups, and complications quarterly.

“We wanted to build a model that represented the people we actually treat in the US—a socioeconomically and racially diverse population,” Laiteerapong explains.

Implications of Early Treatment

The findings from the DOMUS model confirm that early treatment indeed makes a difference in diabetes management. “First-year A1C did, in fact, help predict long-term complications. So yes, those early months matter,” says Laiteerapong. This insight carries significant implications for both clinicians and patients.

While some newly diagnosed patients might prefer time to adjust before starting medication, and some doctors may adopt a “wait and see” approach for mild cases, the model indicates that even modest delays can have lasting effects. The results highlight the importance of timely intervention.

Beyond Individual Care

The questions the model can help answer extend beyond individual care. It reflects not only the consequences of delayed treatment on one patient but also evaluates treatment effectiveness and cost considerations.

“Historically, when we ask policy questions about diabetes, we often can’t do it using real people in real time,” Laiteerapong explains. “We have to estimate or simulate the outcomes using mathematical models. These models help us figure out the likelihood of something leading to a potential health outcome and whether an intervention is worth funding.”

Future Directions and Collaborations

Currently, Laiteerapong’s team is working on external validation using different data sources and pursuing application studies on racial and ethnic disparities in predicted outcomes. Additionally, they are conducting a more detailed study of the legacy effect of early A1C control.

The possibilities for future study are vast, and Laiteerapong and her team are eager to pursue collaborations to use and refine the model. “DOMUS can be used by insurers, policymakers, and public health agencies to guide decisions—especially when clinical trials take too long or aren’t feasible,” she said.

This development follows a growing recognition of the need for personalized and timely diabetes care, underscoring the potential of models like DOMUS to transform healthcare approaches and outcomes.