Cancer cells that detach from a primary tumor can remain hidden in the body for years, lying dormant and evading the immune system until conditions are favorable for metastasis. This process, responsible for nearly 90% of cancer-related deaths, is a critical focus in cancer research. Understanding how these cells survive and spread is paramount to developing effective treatments.

Recent research from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) has shed light on the mechanisms by which metastatic cancer cells evade immune detection. The study, published in Nature Cancer on January 5, reveals that these cells alter their shape to lower surface tension, making it difficult for immune cells to eliminate them. This discovery could pave the way for new strategies to combat metastatic cancer.

Shape-Shifting: A Survival Tactic

According to Dr. Joan Massagué, Director of MSK’s Sloan Kettering Institute, “When cancer cells are round, they have much lower surface tension and it’s harder for the immune cells to attack them and pop them like a balloon.” This insight into the physical adaptations of cancer cells highlights a novel survival tactic employed by these cells.

The study, led by Dr. Zhenghan Wang, utilized cells and mouse models of lung cancer to explore these changes. “Our research suggests that if we can stop cancer cells from entering this soft state, or re-stiffen them, we might help the immune system find and clear dormant metastases before they can seed a new tumor,” Dr. Wang explains.

Mechanisms Behind the Metastatic Defense

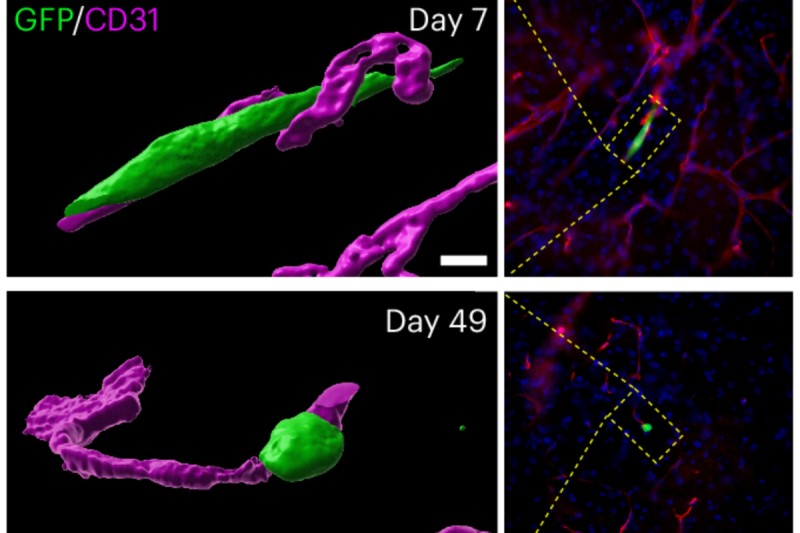

Using an atomic force microscope, MSK researchers observed how dormant metastatic lung cancer cells transition from a firm, elongated shape to a softer, rounder form. This transformation is driven by the signaling molecule TGF-beta and the protein gelsolin, which dismantles the cell’s internal actin scaffolding, reducing stiffness.

“Softer, rounder cells are harder for the immune system’s natural killer cells and cytotoxic T cells to grab onto,” the research showed.

The study further demonstrated that initial exposure to TGF-beta induces an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), making cells more mobile and invasive. However, prolonged exposure increases gelsolin production, softening the cells and enhancing their ability to evade immune detection.

Implications for Future Cancer Treatments

By blocking TGF-beta, reducing gelsolin, or preventing the softening of cells, researchers found that dormant cancer cells could be more effectively targeted by the immune system. This suggests that targeting these pathways could be a promising strategy for preventing metastasis.

Dr. Massagué emphasizes the potential impact of these findings: “We hope that with continuing research into dormant metastasis, we can ultimately prevent metastatic cancer by helping the body eliminate its dormant seeds.”

Research Collaboration and Support

The study was a collaborative effort involving several researchers, including Yassmin Elbanna, Inês Godet, Siting Gan, Lila Peters, George Lampe, Yanyan Chen, Joao Xavier, and Morgan Huse. The work received funding from the National Institutes of Health / National Cancer Institute and the Alan and Sandra Gerry Metastasis and Tumor Ecosystems Center at MSK, among others.

As the battle against cancer continues, this research provides a hopeful avenue for developing therapies that could prevent the deadly spread of cancer by targeting its dormant phases. With further investigation, these findings could revolutionize the approach to treating metastatic cancer, offering new hope to patients worldwide.