RIVERSIDE, Calif. — Researchers at the University of California, Riverside have unveiled groundbreaking findings about Toxoplasma gondii, a pervasive parasite affecting up to one-third of the global population. Published in Nature Communications, the study reveals that the parasite is far more complex than previously understood, providing new insights into its disease-causing mechanisms and the challenges in treating it.

Humans often contract toxoplasmosis through undercooked meat or exposure to contaminated soil or cat feces. The parasite is notorious for its ability to hide within the body, forming tiny cysts in the brain and muscles. While most infected individuals remain asymptomatic, the parasite can reactivate, especially in those with weakened immune systems, potentially leading to severe neurological or ocular complications. Infection during pregnancy poses significant risks to developing fetuses.

Complexity Within the Cysts

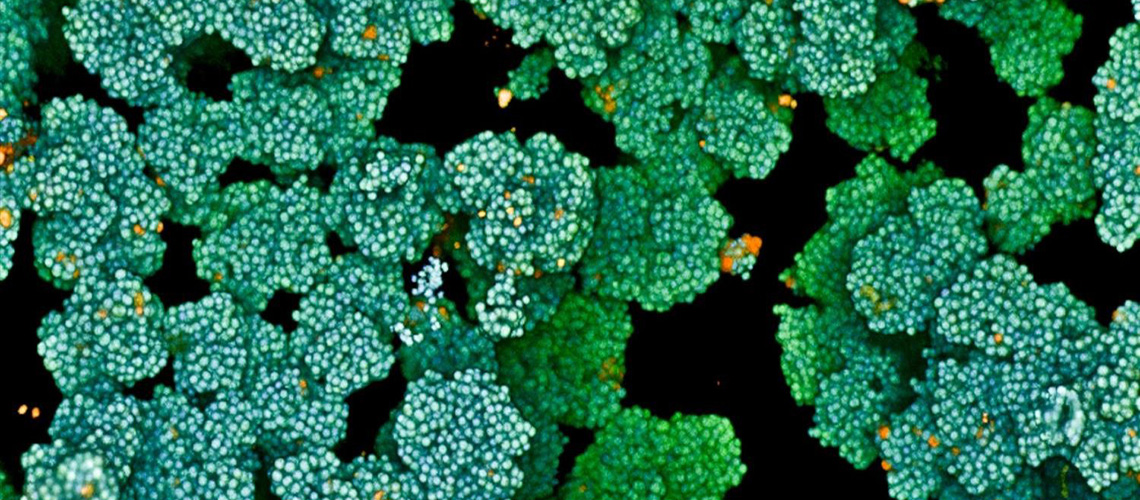

Previously, scientists believed that the cysts contained a uniform type of dormant parasite. However, using advanced single-cell analysis, the UC Riverside team discovered that each cyst harbors multiple distinct subtypes of parasites, each playing different biological roles.

“We found the cyst is not just a quiet hiding place — it’s an active hub with different parasite types geared toward survival, spread, or reactivation,” stated Emma Wilson, a professor of biomedical sciences at UCR, who led the study.

Cysts, which form slowly under immune pressure, are encased in a protective wall and house hundreds of slow-replicating parasites known as bradyzoites. These cysts are significant for their resistance to existing therapies and their role in facilitating transmission between hosts. Upon reactivation, bradyzoites convert into fast-replicating tachyzoites, causing severe diseases such as toxoplasmic encephalitis or retinal toxoplasmosis.

Challenging Established Models

For decades, the Toxoplasma life cycle was understood in simplistic terms, seen as a linear transition between tachyzoite and bradyzoite stages. Wilson’s research challenges this model. By applying single-cell RNA sequencing to parasites isolated from cysts in vivo, the team uncovered unexpected complexity within the cysts.

“Rather than a uniform population, cysts contain at least five distinct subtypes of bradyzoites. Although all are classified as bradyzoites, they are functionally different, with specific subsets primed for reactivation and disease,” Wilson explained.

The study overcame significant technical challenges. Cysts grow slowly, are embedded deep within tissues, and do not form efficiently in standard lab cultures. Most genetic and molecular studies have focused on tachyzoites grown in vitro, leaving the biology of cyst-resident bradyzoites poorly understood.

Implications for Treatment

Current treatments for toxoplasmosis can control the fast-growing form of the parasite but fail to eliminate the cysts. By identifying different parasite subtypes within cysts, the study pinpoints which ones are most likely to reactivate and cause damage, explaining past drug development challenges and suggesting new targets for future therapies.

Congenital toxoplasmosis remains a significant concern, especially when primary infection occurs during pregnancy, potentially leading to severe fetal outcomes. Despite its prevalence, toxoplasmosis has received relatively little attention compared to other infectious diseases.

“Our work changes how we think about the Toxoplasma cyst,” Wilson said. “It reframes the cyst as the central control point of the parasite’s life cycle. It shows us where to aim new treatments. If we want to really treat toxoplasmosis, the cyst is the place to focus.”

Looking Forward

Wilson’s team included Arzu Ulu, Sandeep Srivastava, Nala Kachour, Brandon H. Le, and Michael W. White, with Wilson and White as co-corresponding authors. The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

The title of the paper is “Bradyzoite subtypes rule the crossroads of Toxoplasma development.” The University of California, Riverside, a doctoral research university, continues to be a hub for groundbreaking exploration, impacting communities worldwide.

As research continues, the hope is that these findings will lead to more effective treatments for toxoplasmosis, shifting the focus to the cyst as a critical target in the parasite’s life cycle.