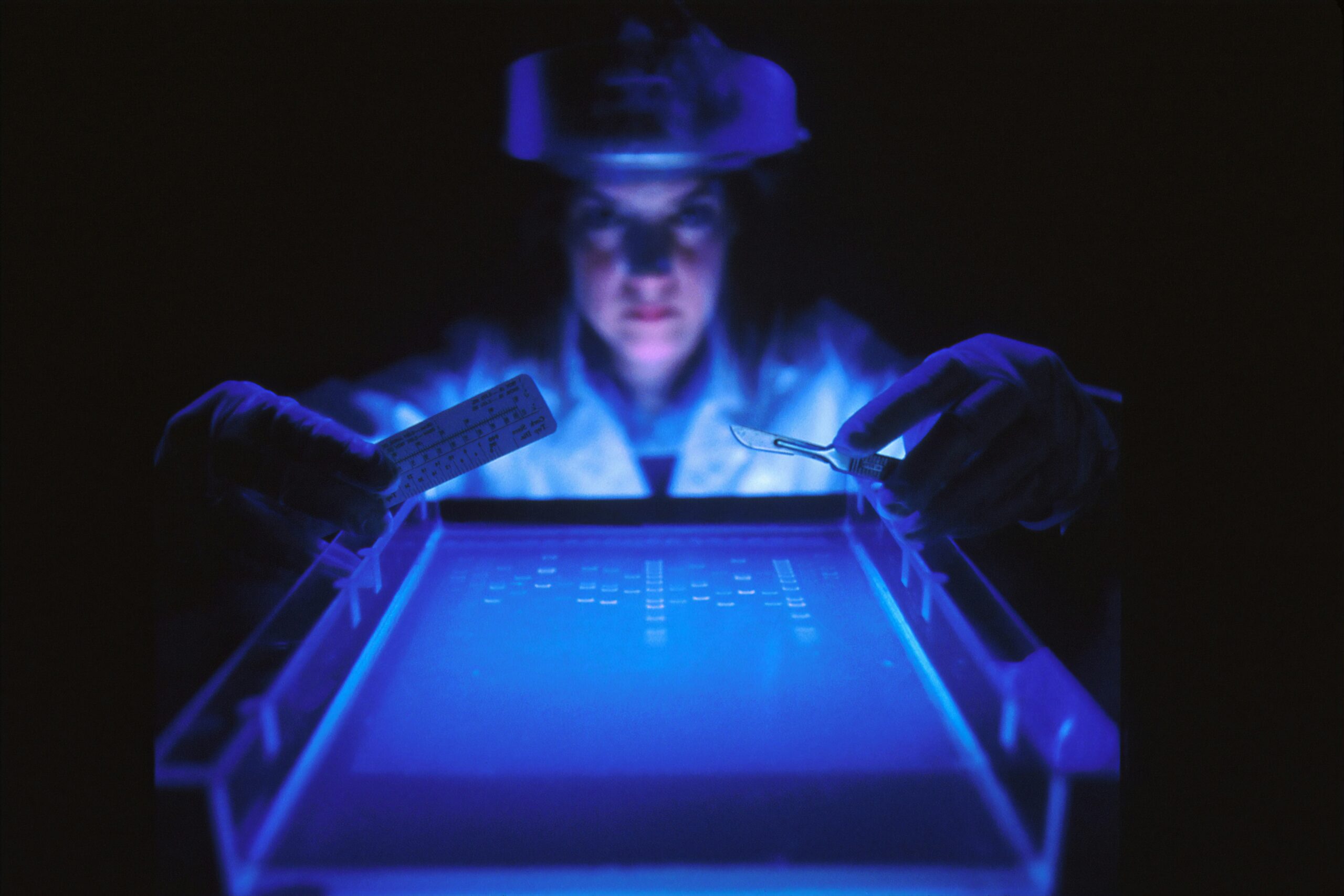

An international research team led by the University of Texas at San Antonio has made a groundbreaking discovery by identifying chitin, the primary organic component of modern crab shells and insect exoskeletons, in trilobite fossils over 500 million years old. This marks the first confirmed detection of the molecule in this extinct group, offering new insights into fossil preservation and the Earth’s long-term carbon cycle.

The findings, spearheaded by Elizabeth Bailey, an assistant professor of earth and planetary sciences at UT San Antonio, suggest that certain biological polymers can persist in the geologic record far longer than previously assumed. This revelation challenges the long-held belief that chitin degrades relatively quickly after an organism’s death.

Implications for the Carbon Cycle

Chitin, the second most abundant organic polymer on Earth after cellulose, plays a crucial role in the planet’s carbon cycle. The study’s results, published in the journal PALAIOS, underscore the importance of understanding how organic carbon is stored in Earth’s crust over geologic time. According to Bailey, “This study adds to growing evidence that chitin survives far longer in the geologic record than originally realized.”

Bailey’s expertise in stratigraphy, field geology, and planetary science contributed significantly to the project. Her perspective as a planetary scientist interested in the role of organic molecules in geochemical processes was instrumental in the research. “My collaborators specialize in modern chitin analytics, and they were excited to apply increasingly sensitive techniques to such an ancient and iconic fossil group,” Bailey explained.

Broader Impacts and Climate Relevance

While the study focused on a small number of trilobite fossils, its implications extend beyond this extinct group. Understanding how organic carbon can persist in common geological settings aids scientists in reconstructing Earth’s carbon cycle and may inform how carbon is stored naturally within the planet’s crust.

The research also holds potential relevance for modern climate discussions. Limestones, formed from accumulated biological remains and widely used as building materials, often contain chitin-bearing organisms. Bailey noted, “When people think about carbon sequestration, they tend to think about trees. But after cellulose, chitin is considered Earth’s second most abundant naturally occurring polymer. Evidence that chitin can survive for hundreds of millions of years shows that limestones are part of long-term carbon sequestration and relevant to understanding Earth’s carbon dioxide levels.”

Research Origins and Future Directions

The research began during Bailey’s postdoctoral fellowship at the University of California, Santa Cruz, supported by the Heising-Simons Foundation’s 51 Pegasi b Fellowship in Planetary Astronomy. Although no other UT San Antonio faculty or students were directly involved in this specific study, Bailey anticipates that the findings will create new opportunities within the university’s Early Earth Lab for future student-driven research into the long-term survival of organic molecules in geological materials.

Bailey’s academic journey has been marked by a strong focus on planetary science. In 2020, she earned her Ph.D. in planetary science at Caltech and received the 51 Pegasi b Postdoctoral Fellowship in Planetary Astronomy, which she took to UC Santa Cruz. Her research centers on how the Solar System, including Earth, formed and evolved over time. Her Early Earth Lab at UT San Antonio builds computer models and conducts laboratory-based chemical analyses of planetary materials, including meteorites and ancient rocks from Earth.

About UT San Antonio

The University of Texas at San Antonio (UT San Antonio) is a nationally recognized, top-tier public research university that unites the power of higher education, research, discovery, and healthcare within one visionary institution. As the third-largest research university in Texas and a Carnegie R1-designated institution, UT San Antonio is a model of access and excellence, advancing knowledge, social mobility, and public health across South Texas and beyond.

UT San Antonio serves approximately 42,000 students in 320 academic programs spanning science, engineering, medicine, health, liberal arts, AI, cybersecurity, business, education, and more. Each year, it invests more than $486 million to advance research programs and generates an economic impact of $7 billion for Texas. In addition to being a nationally preeminent academic health center, the university serves more than 2.5 million patients annually through its comprehensive health system.